Eno

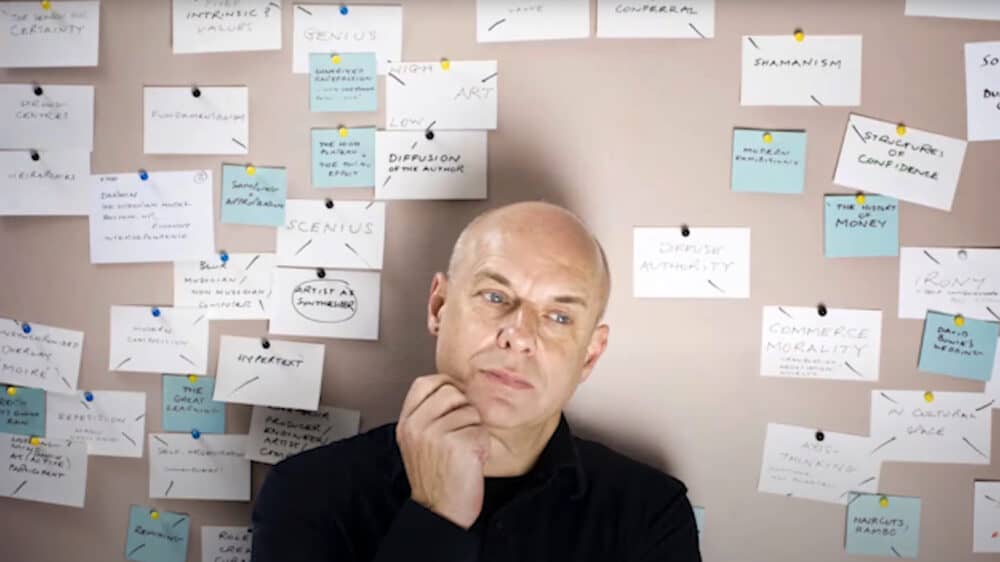

For more than 50 years, Brian Eno has been at the forefront of music, technology and artistic innovation. Hugely influential as a musician, producer, activist, artist and self-described “sonic landscaper,” he began his career in 1970 as a member of Roxy Music, where he was touted as “the scaramouch of the synthesizer.” He left the band in 1973 and released a remarkable series of solo albums—Here Come the Warm Jets, Taking Tiger Mountain (by Strategy), Another Green World and Before and After Science—even as he pioneered the genre of ambient music with the 1978 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports. He has also recorded albums with other musicians, starting with Robert Fripp in 1973 and continuing with John Cale of the Velvet Underground, David Byrne of Talking Heads, Karl Hyde of the British electronic group Underworld and numerous others. As a producer, he has helped define and reinvent the sound of some of the most important artists in music from the 1970s on, including David Bowie, Talking Heads, U2, Laurie Anderson and Coldplay. In the process he has changed the way music is made.

Assembled with access to hundreds of hours of never-publicly-seen footage and unreleased music, Gary Hustwit’s documentary Eno employs groundbreaking technology to accomplish something that had never been done before: a feature film that’s never the same twice. Hustwit and creative technologist Brendan Dawes developed generative software to sequence scenes and create transitions from Hustwit’s interviews with Eno and Eno’s own archive of previously unreleased film footage and music. Each screening of Eno is unique, presenting varying scenes and music in different order. The generative and infinitely iterative quality of the film resonates with the artist’s own creative practice, his methods of using technology to compose music, and his endlessly deep dive into the mercurial essence of creativity.

Photo: Jessica Edwards

Gary Hustwit is a filmmaker and visual artist based in New York. He has produced more than 20 documentaries and film projects, among them the award-winning I Am Trying To Break Your Heart, about the band Wilco, and Mavis!, the HBO documentary about gospel/soul music legend Mavis Staples. After working with SST Records in the late 1980s, releasing music by such bands as Black Flag and Sonic Youth, and running the independent book publisher Incommunicado Press in the 1990s, he started the DVD label Plexifilm in 2001, releasing more than 40 films theatrically and on home video, including work by the Maysles brothers, Andy Warhol and David Byrne.

In 2007 he made his directorial debut with Helvetica, the world’s first feature-length documentary about graphic design and typography. He continued to explore how design affects our daily lives with his subsequent films Objectified (2009), Urbanized (2011), Workplace (2016), and Rams (2018). His films have been broadcast on the BBC, HBO, PBS, Netflix and other outlets in some 20 countries. Eno, his most recent project, uses generative technology in its creation and exhibition. In the process of making it he became CEO of Anamorph, a generative media studio and software company he co-founded with Brendan Dawes.

Photo: Nathan Gallagher

Brendan Dawes is a British artist and designer known for playful yet thought-provoking explorations of data, technology and everyday objects. Rooted in remix culture, his work often re-contextualizes existing materials to examine how people experience the physical and digital worlds. By blending code, found objects and tactile interfaces, he creates works that invite audiences to consider the poetry in mundane moments and the hidden structures in complex data.

Dawes first gained recognition for works such as Cinema Redux, a visualization that deconstructs entire films into a series of cinematic fingerprints, revealing new patterns in familiar content. This approach – taking existing cultural artifacts and reshaping them to uncover fresh perspectives – exemplifies his commitment to remix culture, something he first explored when creating loops on tape for bootleg breakbeat albums on vinyl. Drawing on influences from design, architecture, and Dada, he frequently references the concept of the “readymade,” using everyday items as foundations for new experiments in visual form and interactivity.

Dawes is Visiting Professor of Computational Art at Manchester Metropolitan University. His work has been 3D-printed on the International Space Station, honored by Fast Company and featured in exhibitions around the world. Cinema Redux was added to the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2008.

Q&A WITH THE FILMMAKERS

Gary Hustwit and Brendan Dawes were interviewed via videoconference by Lance Weiler, founding director of the Columbia Digital Storytelling Lab.Lance Weiler: This work is incredibly exciting, particularly in terms of the potential of generative systems and how stories evolve and change. There’s so much that points to the future, and I’d love to start with the origin. What inspired you to approach a documentary about Brian Eno through a generative system? How did the idea emerge, and what were you hoping to explore, or reveal?

Gary Hustwit: The project really started from a place of frustration—or boredom—with the form of cinema and documentaries, which is what I’ve primarily been making. I’ve always compared it to music. As a musician, you perform your work and change it every night, even if it’s the same song. There’s a freedom there. Cinema doesn’t have that. Once the film is made, it’s fixed. It’s like a musician going on tour and pressing play on a record while walking off the stage.

I started wondering: why can’t I be surprised by my own film? Wouldn’t it be great to see it with fresh eyes every night, just like the audience does? That’s when I reached out to Brendan to see if there was a software solution—could we make a film that felt cinematic but transformed every time it was shown?

Brendan Dawes: That email came in January 2019, and I still have it. It’s part of the project’s documentation now. I love working on new, exciting things—especially when I don’t know how to do them. That’s the beauty of creativity, especially with digital tools, which change constantly. For those of us who are curious by nature, it’s about staying a little uncomfortable.

So when Gary reached out, I immediately said yes. This was the kind of thing I wanted to do all the time. I had no idea how we’d do it, but we both felt there was something we could build. We always wanted it to be cinematic. We didn’t want it to just be a random generative thing. We’re both cinema buffs, and we wanted it to feel like a real film.

Gary: When I first proposed a traditional documentary about Brian in 2017, he turned it down. He hated biodocs, where someone else tells your story. He didn’t want that. So when we began developing the generative platform, I realized this might be the perfect approach for him—he’s been innovating with generative software for music for years. After about six months of prototyping, we showed him a demo. He was blown away, and that’s when the real project began.

Lance: One thing that struck me while watching was how you visually conveyed the generative aspect, especially the way the code appears on the left side of the screen during transitions. That subtle cue was brilliant. Can you talk about how you balanced the experimental nature of the piece with the need to keep it cinematic and accessible to audiences?

Gary: That balance was key. We tried some versions that were purely experimental mashups, but they didn’t work as well. So we approached the material as we would any documentary—curating, crafting, interviewing Brian, going through his archives.

For our editors, this was completely new. Normally, they’re crafting a linear narrative. In our case, they didn’t even know if the scenes they were editing would appear in the final version. Or what would come before or after. It totally changed how we thought about storytelling. We started categorizing the types of scenes: biographical beats, creative processes, music sequences. We developed a rhythm and taxonomy that allowed the film to work regardless of sequence.

“Sometimes it glitches. Once we had a bug that caused an eight-minute glitch sequence—but half the audience thought it was intentional. That made us realize: there are no rules.”

Brendan: At the beginning, we weren’t even sure what form the film would take. We talked about whether the system should have a visible role—almost like an actor in the film. But we didn’t want a cheesy computer voice announcing, “Now playing scene X.” We wanted a light touch.

I actually created the original code glitch effect while on holiday. That moment of clarity came in the sun—I opened the laptop, experimented, and it worked. We built on that and integrated it into the system. What you see on screen is real—it’s the system thinking. From there, it created a visual grammar for the film.

Gary: And we didn’t stop after Sundance. We kept adding footage, tweaking functionality, and reworking the structure. That’s the beauty of a generative system—it evolves. We made a 90-minute theatrical version, but we also created a 168-hour version for the Venice Biennale that never repeated.

It’s not just about doing something cool with code. It has to resonate emotionally. Brian’s ideas, his philosophies—they needed to land. And the modularity let us play with how those ideas unfold differently for each viewer.

Lance: Let’s talk about your collaboration. You mentioned that initial email was a green light for Brendan. How did the two of you actually work together? What did your process look like?

Brendan: We’ve known each other for a long time and always wanted to collaborate. We come from different worlds. I create generative systems that make things, and I’m often surprised by the results. Gary, as a director, is guiding every moment. That tension was creatively fruitful.

We mostly communicated through texts and emails—probably thousands over five years. Every iteration was logged, and we kept refining. Dropbox was our lifeline.

Gary: It was filmmaking and generative digital art meeting in the middle. Brendan would build something, we’d try it, maybe use it in a way he didn’t expect, and that would inspire new features. It was a constant feedback loop. Eventually Brendan had to build a GUI—a user interface so that I and the editors could work with the system. Before that only he could operate it, and that wasn’t sustainable.

Brendan: I remember when we got into Sundance, I panicked. We needed an actual tool, not just code. So we created something functional, intuitive. The system became a performance tool. It could render dynamic sound mixes and stitch together a film in real-time—no frame skips. That took a lot of debugging.

Gary: And it worked. I can now hit “generate” and a new version comes out. I don’t even have to watch it. Sometimes it glitches. Once we had a bug that caused an eight-minute glitch sequence—but half the audience thought it was intentional. That made us realize: there are no rules.

Lance: I was also struck by the Oblique Strategy cards. Can you talk about their inclusion and how you managed emotional resonance across so many versions?

Gary: The cards were a fun experiment. They started in Brian’s studio, and we thought: what if someone pulled a card and it diverted the film? It was another way to show change and fluidity in the structure.

As for emotional resonance, it all came down to the data set. Every clip, every scene had to have a creative takeaway. That was my goal—to make a film about the creative process. It’s not random. There are structural bookends, and we made sure that in every version, viewers would encounter moments that inspire.

“Embrace the idea of surrender. That’s something Brian often talks about—building systems that allow for surprise. As filmmakers, we’re taught to control everything, but letting go can be liberating.”

Lance: Sitting where you are now, after building this from 2019 to today, what advice would you give others exploring generative storytelling?

Brendan: Stay open. Be willing to listen and learn. I had to understand how documentary filmmaking works, just as Gary had to understand how generative systems work. Start small—a tiny prototype—and keep building. And always remember your core. For us, it was about Brian. It wasn’t about showing off tech. It was about telling his story in a new way.

Gary: I’d say embrace the idea of surrender. That’s something Brian often talks about—building systems that allow for surprise. As filmmakers, we’re taught to control everything, but letting go can be liberating. This project taught me that the audience doesn’t need everything spelled out. People will make connections. Every version of the film is someone’s favorite. That subjectivity can be a strength.

Lance: This feels like a signal of what’s next. It builds on what Eno’s done, while opening a space for the future of generative storytelling. It’s post-cinema. It’s speculative. And it’s deeply personal for each viewer. I think it’s a remarkable achievement.

Gary: Thank you. That means a lot. It’s hard to describe what we’re doing while we’re still doing it. But it definitely opens doors to things we couldn’t even imagine before. Now that we’ve built the platform, we’re starting to see new possibilities—new kinds of films, new ways to tell stories.

Lance: And the name of the platform?

Gary: It’s called Brain One. An anagram for Brian Eno. It just felt right.

IN THE MEDIA

“Most movies are made up of juxtapositions of scenes, carefully selected and designed by the editor. But ‘Eno,’ directed by Gary Hustwit, turns that convention on its head. Every version of the movie you see is different, generated by a set of rules that dictate some things about the film, while leaving others to chance. . . .

“The word ‘generative’ has become associated with artificial intelligence, but that’s not what’s going on with Eno. Instead, the film runs on a code-based decision tree that forks every so often in a new path, created for software named Brain One [that] generates a new version of the film on the fly every time the algorithm is run. . . . According to the filmmakers, there are 52 quintillion (that is, 52 billion billion) possible combinations, which means the chances of Brain One generating two exact copies of Eno are so small as to be functionally zero.”

“[The film’s] components aren’t necessarily any different than those in most music documentaries, although they focus strongly on ideas and concepts rather than a tidy biographical arc. But they are sorted and resorted in abrupt, unpredictable ways that keep the eyes and mind jumping.

—Los Angeles Times

“Premiering at the Sundance Film Festival on the event’s opening day, Eno gave a packed house at the Ray Theater a glimpse into the life of Brian Eno — a portrait of an artist pulled together on an algorithm’s whim. It was a singular experience, impossible to replicate. . . . Were you to attempt this on almost any other subject, the idea might be gimmicky to a fault. Applied to a conceptual musician like Brian Eno, who couldn’t play an instrument when he joined Roxy Music but took up the synthesizer because it was new and thus ‘there were no rules on how not to play it,’ the approach feels like it might be the only way to properly talk about Eno.”

—Rolling Stone