Hypnospace Outlaw

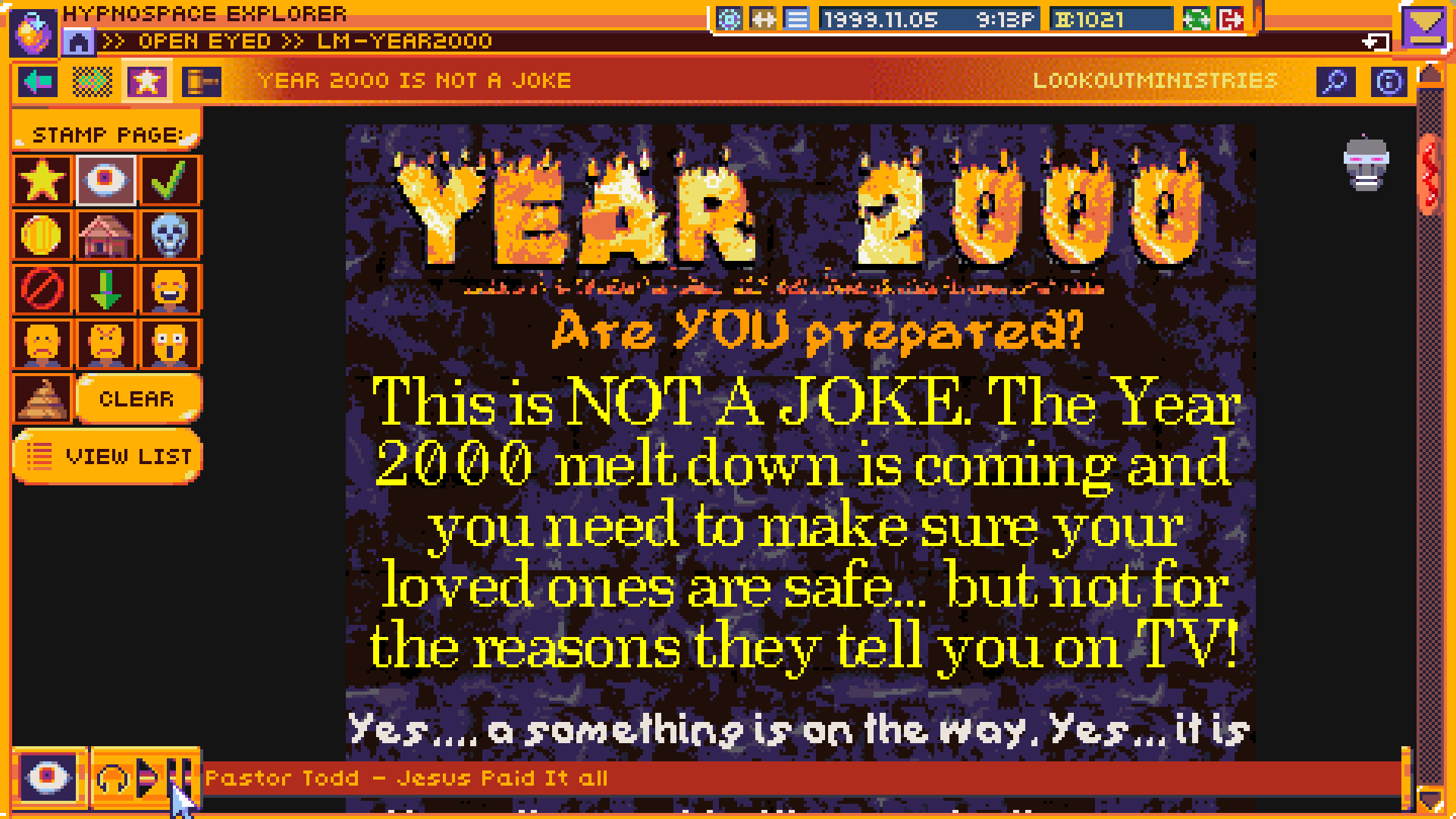

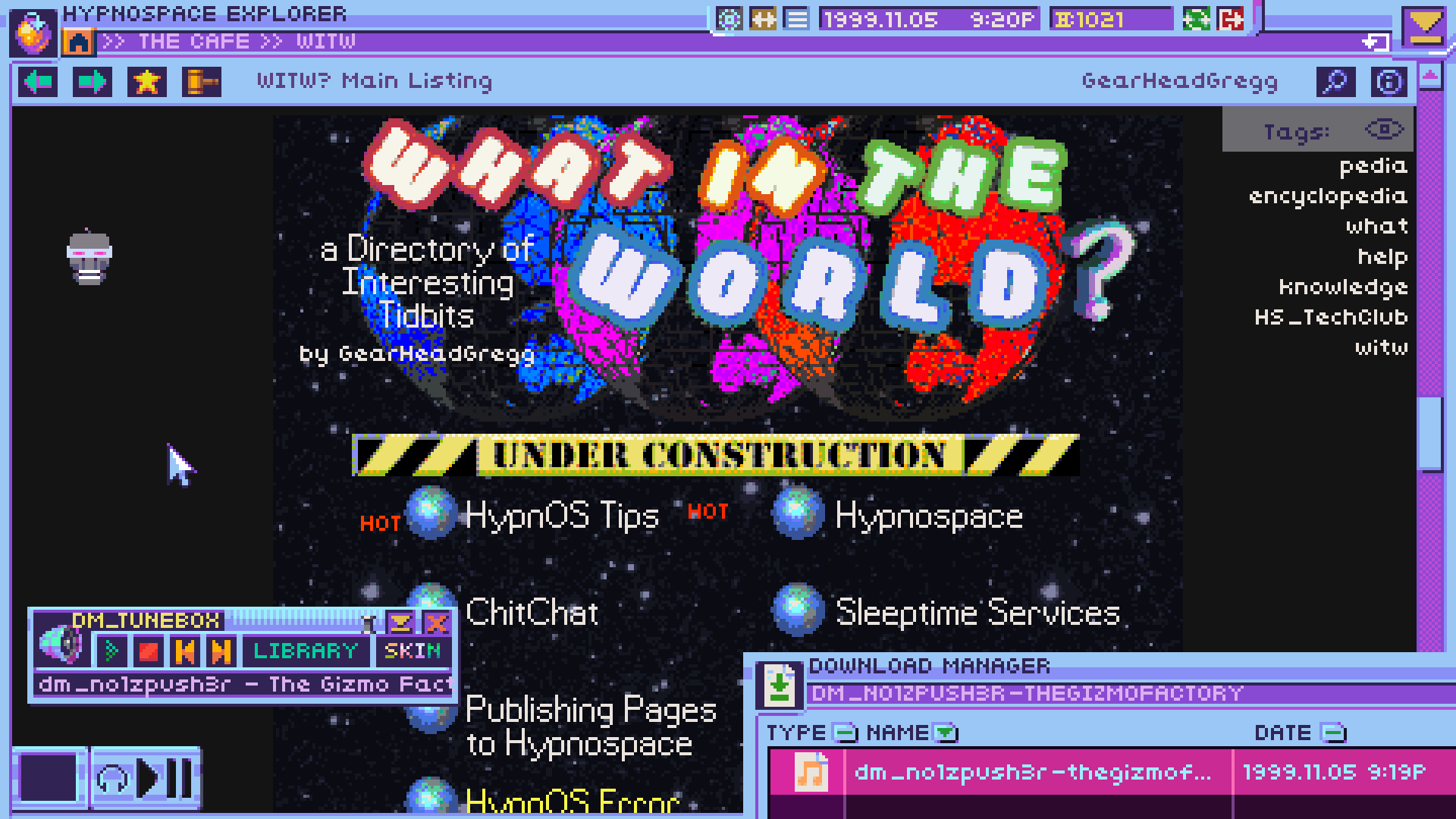

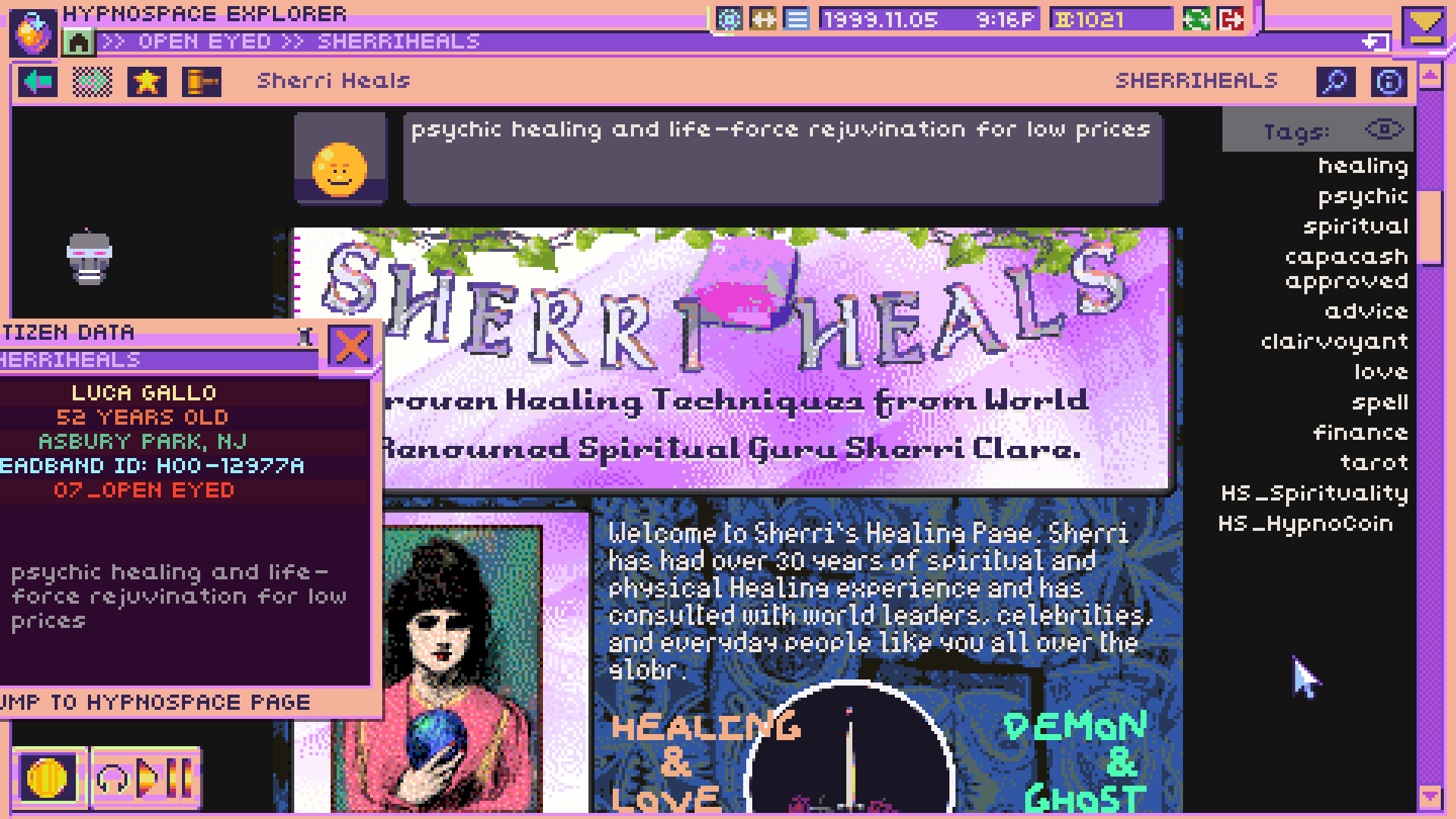

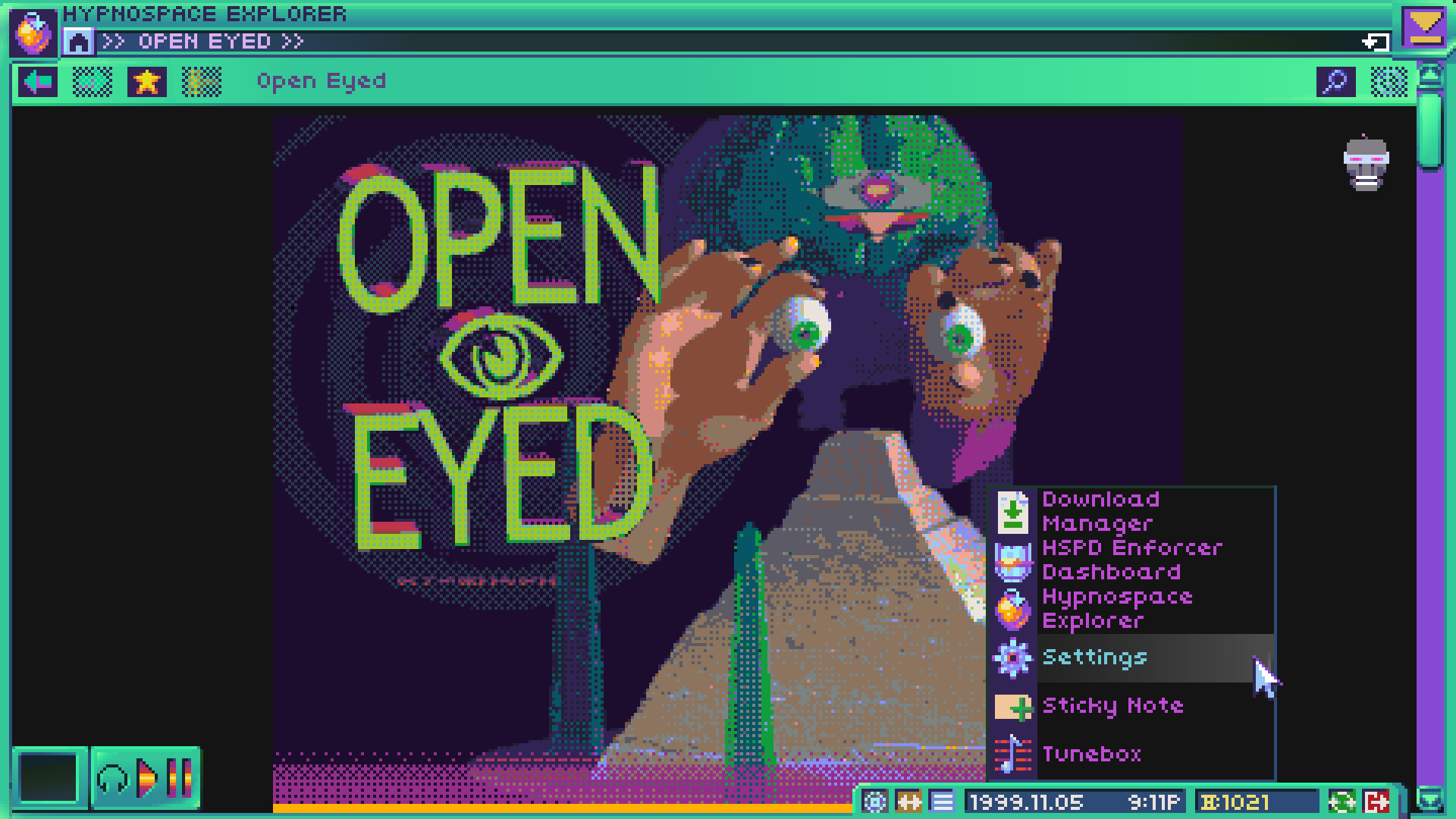

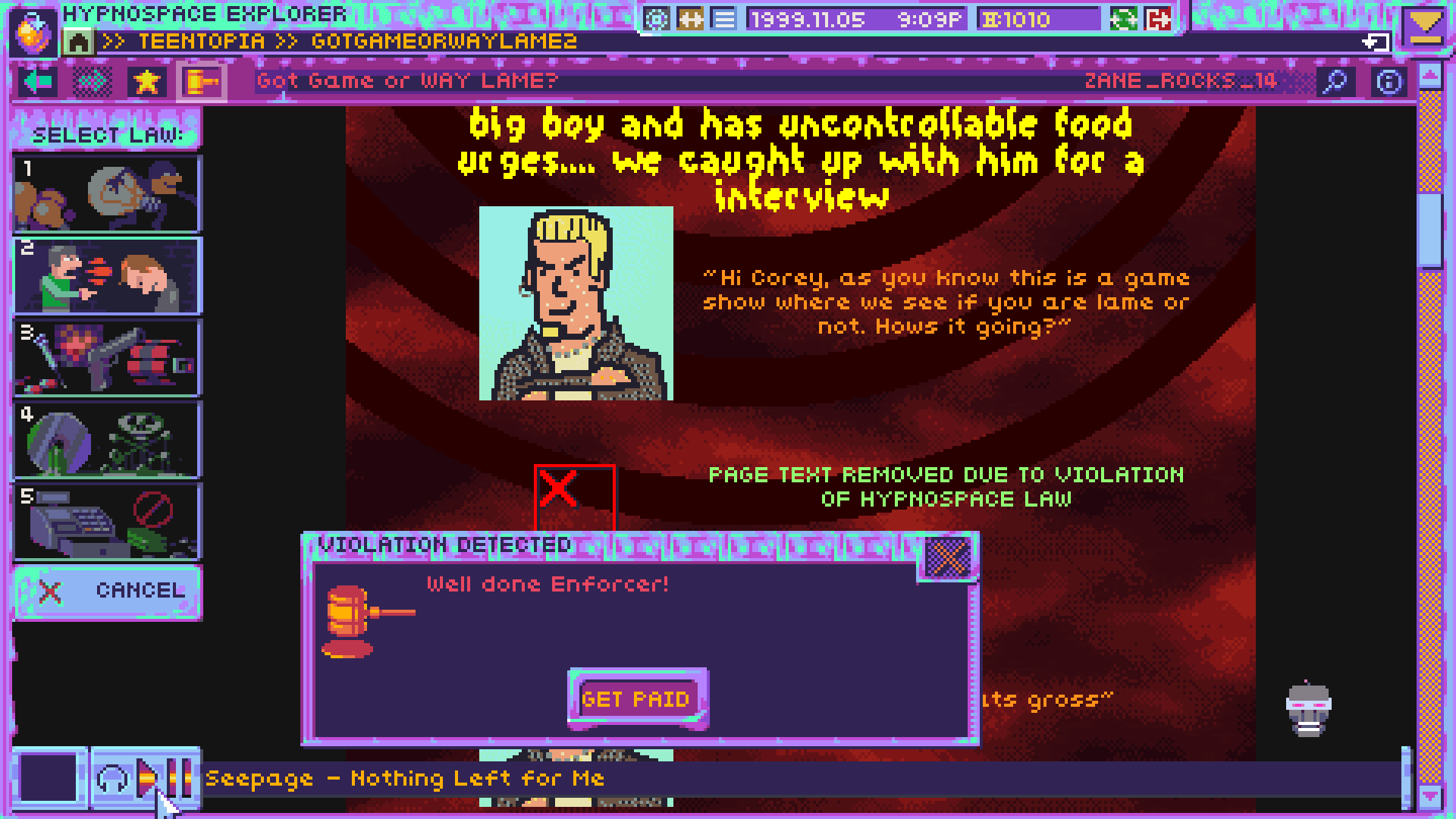

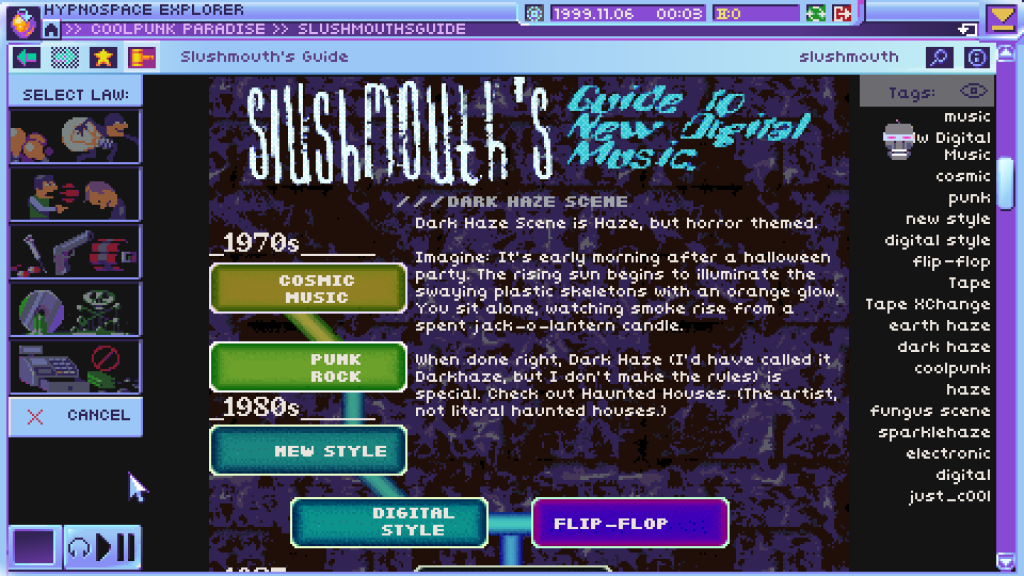

Sleeptime Computing, a new technology allowing users to browse the internet while they sleep, has captured the world’s imagination. Hypnospace is the first and most popular Sleeptime service, and they’ve accepted your application to serve as an Enforcer. As the uncertainties of a new millenium consume the bustling digital metropolis, will you use your new post to help your fellow Hypnospace Citizens or slam them with violations to amass a HypnoCoin fortune?

Jay Tholen started making games and honing his pixel art skills as a kid in the late 1990s with early game-making programs like Klik & Play and The Games Factory. After dropping out of high school, Tholen took a break from making games and took a series of telemarketing job and started a prog rock band. In 2015, he collaborated with A Jolly Corpse on the critically acclaimed point-and-click adventure game Dropsy. Born and raised in Florida, he now lives in Münster, Germany. Among his favorite famous people are Jesus, Mr. Rogers and Brian Eno.

THREE QUESTIONS FOR THE CREATOR

Why this? Why now?

Jay Tholen: The concept for Hypnospace Outlaw originated in a small microgame named Hypnospace Enforcer I made back in 2014 during the development of my other game, Dropsy. Players assumed the role of Enforcers tasked with apprehending netizens who had broken laws using their virtual cop cruiser on a pastel-hued ‘information superhighway.’ As players approached their targets, more details about the lives of the suspects would reveal themselves and ideally players would empathize with them a bit. I built a little lore bed around it involving futuristic headbands that folks wore to access the internet while sleeping.

After Dropsy was finished I started working on a fully featured sequel to Hypnospace Enforcer with the highway as the main meat of the game and the HypnOS operating system as more of a glorified level select screen. You’d hunt violators down on the web and then go after them on the highway. The response to gifs and clips of the faux-OS garnered astronomically more attention than the car sections did, and fiddling with a fake operating system was tons of fun, so development veered pretty hard in that direction. Bringing on Mike Lasch to code also cemented it as a mostly-OS game because he kept adding all sorts of neat fiddly bits.

At the same time I became interested in the history of the early web which pushed Hypnospace into becoming the tale of dot-com era excess that it is now. The timing is pretty great since it seems that folks are cycling back into enjoying the look and feel of that era again.

What surprised you as you were making it?

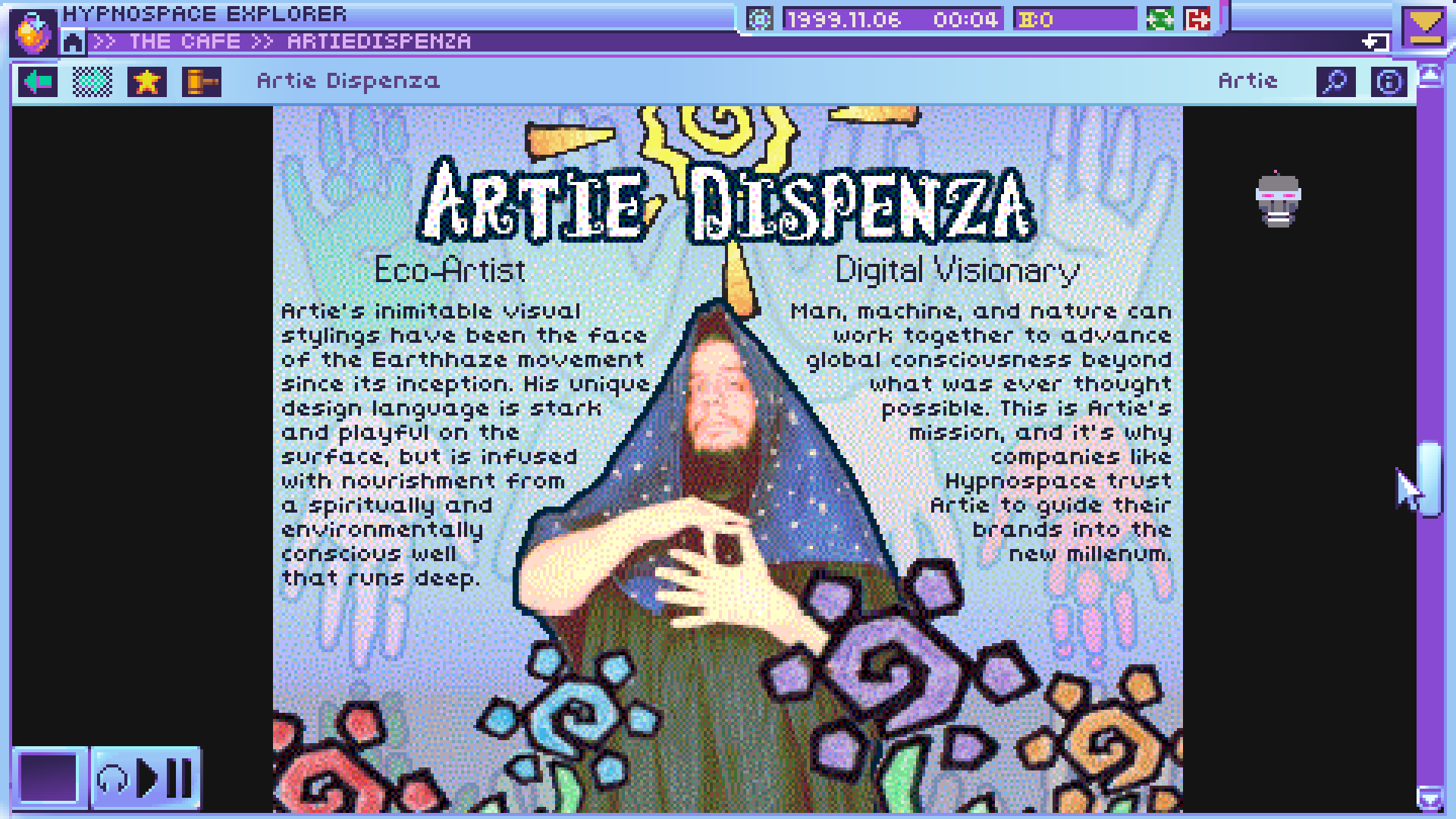

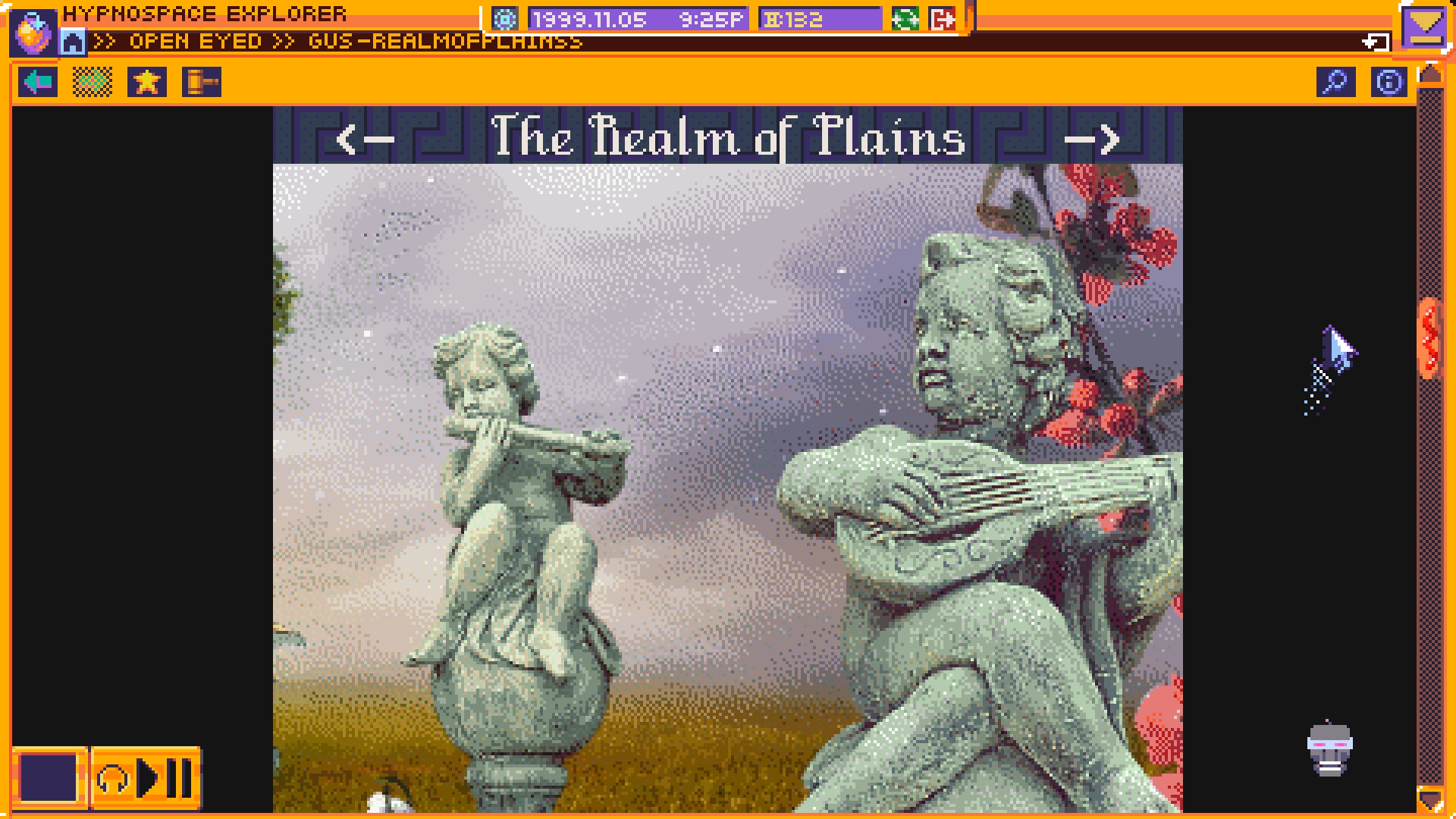

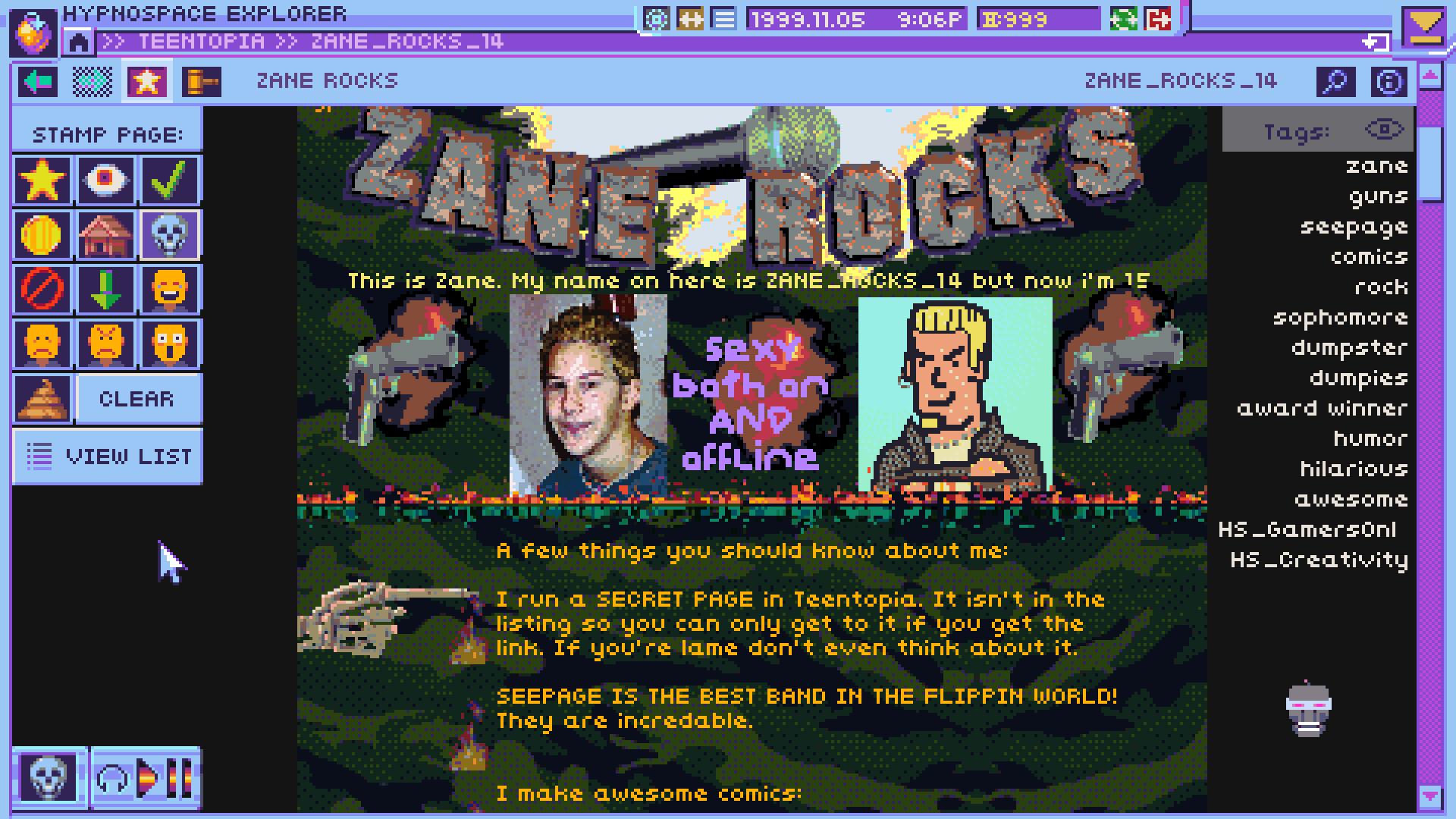

My internet archive and Geocities spelunking resulted in my developing a taste for the look and design of the old web that transcends appreciating it for its kitsch. I genuinely like how those websites looked aesthetically and felt to explore. I don’t even find them charmingly ugly, they’re just good looking to me now.

They were also infinitely less annoying to navigate than sites today. It wasn’t perfect by any stretch. Search was inefficient and it was hard to find specific bits of information, but the amount of open sharing folks did was something I doubt we’ll ever really return to. Shrines to beloved pets, poems, recipes, etc. Folks didn’t seem to stop and consider if anyone else out there cared to see their postage stamp sized photos of their trip to Norway or whatever.

Social media has become a homogenized stew that only encourages content that’s novel enough to accumulate clicks. Folks still share pet stuff and recipes and book reviews, but we have formalized separate channels for each of these things and the purpose of each is to maximize ad revenue.

I was also surprised at how absolutely bonkers the dot-com era was. Investors were throwing money at garage startups run by cocky upper-middle-class teenagers, and the result was incredibly weird. Net Café and Computer Chronicles as well as interviews with dot-com folks via the Internet History Podcast are good resources to catch up on that time period.

What was the most challenging aspect for you?

The most challenging aspect of making Hypnospace Outlaw was turning it from a toy operating system and fake internet into a game with progression systems. For a few years it was just a sandbox that we kept adding fun little features to with no real narrative progression to speak of. Our narrative designer, Xalavier Nelson Jr., helped us massively on that front.

“Even within the first hour, it’s apparent that there’s something uncomfortable about being an enforcer; there’s some satisfaction in reporting a teen’s cyberbullying, but dobbing in a first-grade teacher for posting her kids’ copyright-infringing drawings of a famous cartoon character feels off. Things that you try to stamp out quickly multiply and proliferate across the web, becoming impossible to track. A pretty elaborate story unfolds as you work through your cases and explore the dark recesses of the web, which raised questions for me about online control and censorship that have become even more essential in 2019.”

“So there’s . . . a strange glimpse into a world that never really was, and yet feels like it absolutely could have been. It’s a thrilling mystery, and a near-impeccable use of tone and visuals, but above all it’s a series of questions: what do these communities mean to people? What did they create, why did they create them, who created the scaffolding on which they were built? Who can destroy them? What happens after they’re gone?”