Presence

I wanted to create a place where you feel connected. You make the artwork and the artwork makes you. Presence shows your relationship with the environment and how we can influence it.

—Daan Roosegaarde

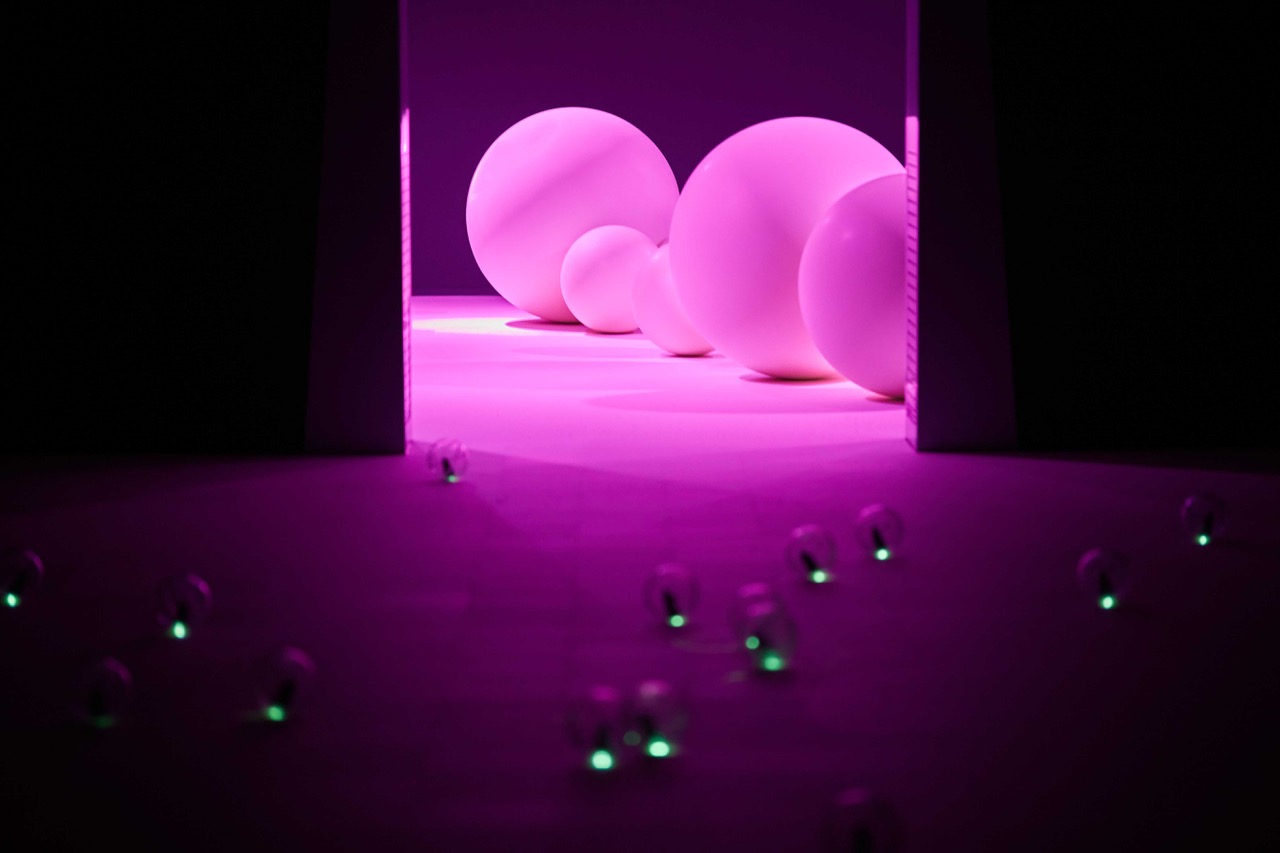

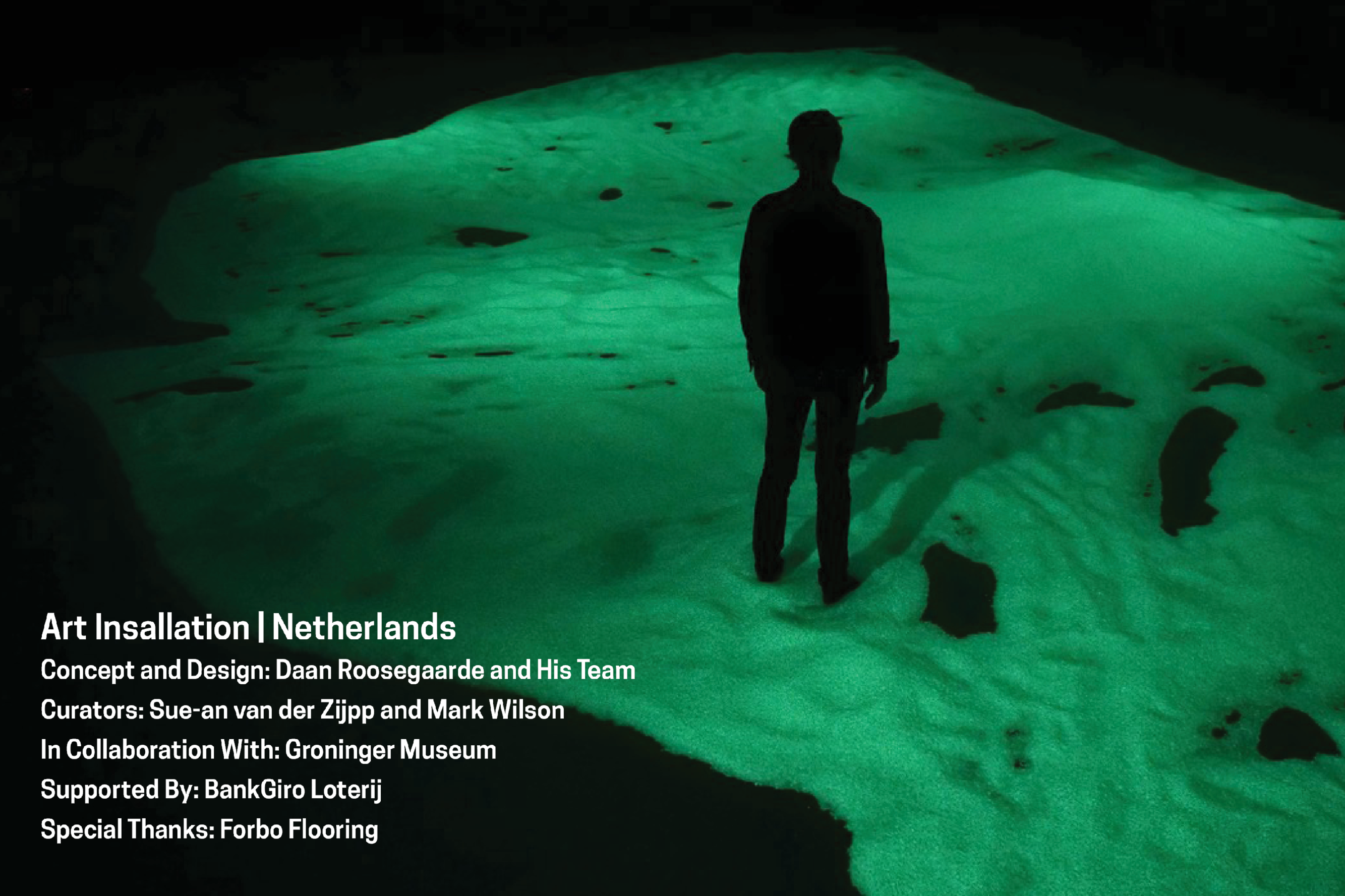

Presence is an interactive, immersive, luminous artwork that tells a story about our presence in the world. Developed for the Groninger Museum and exhibited there from June 2019 to January 2020, the work is completely different from the usual museum experience. It is composed of many different elements, from tiny luminous beads to large rollable balls, that create a phosphorescent landscape that’s activated by ultraviolet light. As a result, Presence responds to touch and movement: Visitors walk into a luminous landscape that changes color and shape in response to their presence.As a pioneer of the landscape of the future, Roosegaarde investigates the concept of the Dutch word “schoonheid” in its dual meaning – beautiful and clean – as exemplified by new social core values like clean air, clean water, and clean energy. He was inspired to make Presence by climate change and a desire to improve the landscape. In the work, visitors’ traces, which eventually disappear to make room for new ones, symbolize the impact of humans’ presence on earth. Another source of inspiration was the landscape and environment art of the 1960s and ’70s in which interactivity and awareness of the earth’s vulnerability played an important role too. Those artists made outdoor landscapes an integral part of their art; Roosegaarde takes his landscape inside the museum walls.

Unlike most exhibitions, which demand that art should be viewed from a distance, Presence encourages physical interaction and immersion. Although the installation is the product of innovative material and technical research, it comes across as highly intuitive and immersive. Different areas allow visitors to experience various changes in perspective – from large and solid to small and mobile, from dark to bright. In one gallery, futuristic spheres draw lines on the floor. Another seems filled with luminous stardust, calling to mind a vast city seen from an airplane. Other spaces appear to scan visitors by recording their presence in silhouettes and patterns. The interaction between visitor and work creates constantly changing visual impressions. Not only looking and observing but, most of all, touching, feeling and moving are essential.

“They look like jellyfish, transparent luminescent organisms from the deep sea. They lie still on the ground, only visible because the floor emits a mysterious light. Until they are touched and the room suddenly comes to life: the jellyfish start to move, leaving behind a luminous trail. The floor, previously like an empty canvas, suddenly displays a tangle of whimsical, green luminescent lines. Some look like children’s scribbles, or maybe rock carvings or surrealistic automatic drawings. It’s a weird and wonderful as well as enchanting spectacle. Also, it is work that, without any additional explanation, encourages people to touch, push, roll, draw and write. It may even lead to joint experiments – and that is exactly what it is supposed to do. . . .

“Covering an entire floor, the installation, its form and colour changing continually due to interaction with visitors, is like a landscape full of ever-new and unexpected possibilities. The emphasis on physical interaction with the work is deliberate. Its potential role as a powerful agent of change may well be the heart of this installation. . . . Visitors actively (co)design the installation, but their activity also affects them. The visible impact all visitors have on this environment makes them hyperaware of their own presence. Presence’s extraordinariness lies in this reciprocity, in the way interaction with the installation affects visitors’ cognition, the way they acquire knowledge, and creates new preconditions that make alternatives conceivable.

“This means Presence is also an inquiry and an experiment into forms of display in which not only sight, but also immersion, touch and movement play an important part. Actively participating visitors break down role patterns and overcome traditional contrasts such as spectator-work of art, thinking-acting and body-mind. Roosegaarde radicalizes this by including visitors in his work as ‘moving parts.’ Typically, his hybrid work cannot be described by clear-cut definitions. This dovetails with the policy of the Groninger Museum to focus on artists who investigate and redefine the boundaries of their own discipline.”

—Sue-an van der Zijpp, Curator of Contemporary Art, Groninger Museum

In conjunction with the exhibition, Phaidon published the English-language monograph Daan Roosegaarde. A Dutch translation was published simultaneously. Featured in the book is an essay by Carol Becker, dean of faculty of Columbia University School of the Arts. In October 2019, Roosegaarde’s light installation Waterlicht was exhibited at Columbia’s Lenfest Center for the Arts, accompanied by a conversation between Roosegaarde and Becker. Daan Roosegaarde (born 1979 in South Holland) is a creative thinker and maker of social designs that explore the relation between people, technology and space. From an early age Roosegaarde has been driven by nature’s gifts, such as luminous fireflies or jellyfishes. His fascination with nature and technology is reflected in his iconic works, among them Smog Free Project, a large outdoor air purifier which turns smog into jewelry; Van Gogh Path, a bicycle path that glows at night, and his most recent work, Space Waste Lab, designed to visualize and capture space waste.

Daan Roosegaarde (born 1979 in South Holland) is a creative thinker and maker of social designs that explore the relation between people, technology and space. From an early age Roosegaarde has been driven by nature’s gifts, such as luminous fireflies or jellyfishes. His fascination with nature and technology is reflected in his iconic works, among them Smog Free Project, a large outdoor air purifier which turns smog into jewelry; Van Gogh Path, a bicycle path that glows at night, and his most recent work, Space Waste Lab, designed to visualize and capture space waste.

In 2007 he founded Studio Roosegaarde, where he works with his team of designers and engineers on landscapes of the future. Located in a former glass factory in the harbor of Rotterdam, Studio Roosegaarde is also known as the Dream Factory. Here new innovations are developed from concept to artistic installations. The Studio has experience in public space commissions in cities such as Rotterdam, Beijing, Paris, Eindhoven and Stockholm. It also has a pop-up studio in Shanghai.

Roosegaarde graduated from the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam in 2005 with a Masters in architecture. He is a Young Global Leader at the World Economic Forum, a visiting professor at the University of Monterrey in Mexico, an advisor for Design Singapore Council, a visiting professor at Tongji University Shanghai and a member of the NASA Innovation team. He has been selected by Forbes, Wired and Good 100 as a leading creative change-maker.

THREE QUESTIONS FOR THE CREATOR

Why this? Why now?

Daan Roosegaarde: Presence is about creating a place where you feel connected. It does not provide direct solutions such as the Space Waste Lab or Smog Free Project but rather aims for the layer above that; the intuition and creativity of people. The fact that you can touch everything and your physical presence creates an atmosphere in which you make the artwork, but the artwork also makes you. I believe that we are disconnected from the world around us, a lot of global challenges seem far away from our daily life. By making people see the impact they have on the landscape you trigger them to take more care. People won’t change because of facts or numbers, but if we can trigger the imagination of a new world, that’s the way to activate people. If we all would be curious and caring for the future we would do a lot better.

The exhibition ends with the famous quote of the Canadian author Marshall McLuhan: “On spaceship Earth, there are no passengers, we are all crew.” I think this is very important for me, not just to be a consumer, but to be a maker. Every visitor will have his or her own actions after the exhibition. You create a dream world to change the perspective of what reality is.

What surprised you as you were making it?

Light for me is not decoration but an activator – to create a direct relationship between you and the landscape, but also between you and other people. It is very interesting how in the exhibition there is no more hierarchy between people, from CEOs to kids – everybody interacts with each other. People also interacted with the work in ways we could not have imagined, and that is the beauty of it people take over the space you have given to them and make it their own.

What was the most challenging aspect for you?

Creating Presence is something I never have done before. Groninger Museum approached me four years ago with the request for an oeuvre exhibition. That sounded really scary for me, my previous artworks with a lot of signs “please do not touch.” So I rejected that idea. We proposed something radical: an all-new artwork as a layer of light and interaction in the museum, with a please touch attitude. The Groninger Museum said yes (which I thought was brave), and we got to work.

The first prototypes we made at Studio Roosegaarde really sucked. The reason was that we indeed are so used to using light, wind, headlights of cars (in the Gates of Light project). But inside the museum these elements are not present — it felt like wind in a glass bottle, which is not wind anymore. So we had to zoom out and start to work with the context of the museum more. We started to remove these annoying “please do not touch” signs and the very ugly light-emitting green “exit” signs (which took eight months of negotiation with the fire inspectors). Then I put the people, you, me, the visitor central in the work. You would make the artwork, without your physical presence it would not exist. Then the prototypes started to become way better.

Inside the Rotterdam “Dream Factory.” Photos courtesy Daan Roosegaarde

Studio Roosegaarde is located in a former glass factory in Rotterdam’s harbor

“‘What you find is one big light-emitting landscape that shows the impact you have on the world around you,’ says Roosegaarde. ‘The room scans you, and shows your imprint as you move along it in a way that becomes more organic and playful. There are no “do not touch” signs, because they isolate from reality.

“‘The project scared the shit out of me when we first started, and I was afraid it was too abstract, but people have immediately engaged with it in a beautiful way. There’s no hierarchy. From CEOs and ministers to students, the moment they’re inside, everyone interacts, explains and shares together. And they’re more weird, obsessive and crazy than I could ever imagine.’”