The Game of Whispers

The Game of Whispers is an interactive and generative artwork that draws parallels between political intrigue in the Mughal Empire during the reign of Shah Jahan (ruled 1628-1658) and the role of AI-driven disinformation in today’s world. Set within a digitized rendition of Delhi’s historic Red Fort, the piece explores how rumors, manipulation, and shifting power dynamics mirror the way modern technology, particularly AI, shapes narratives and distorts truth.

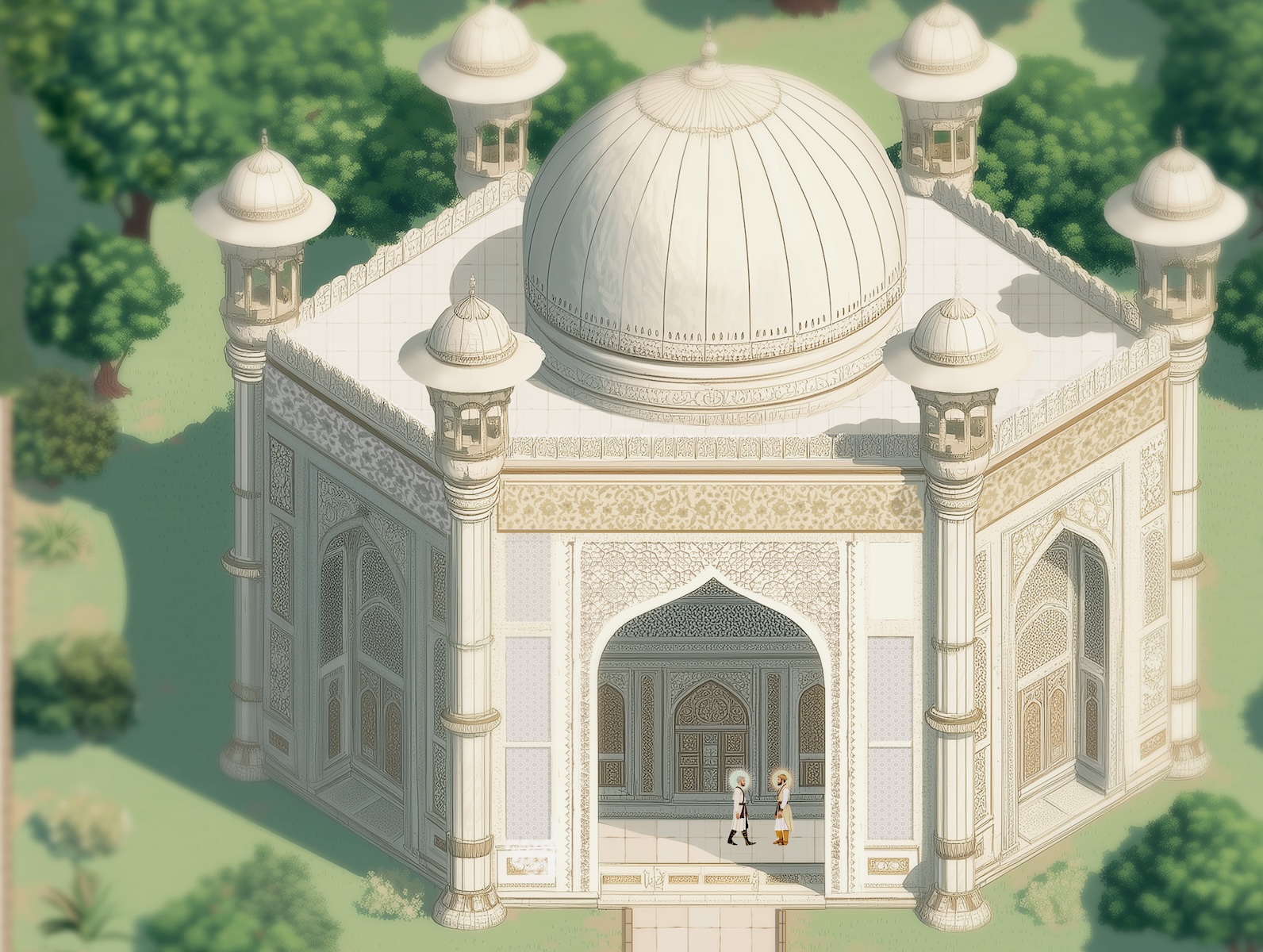

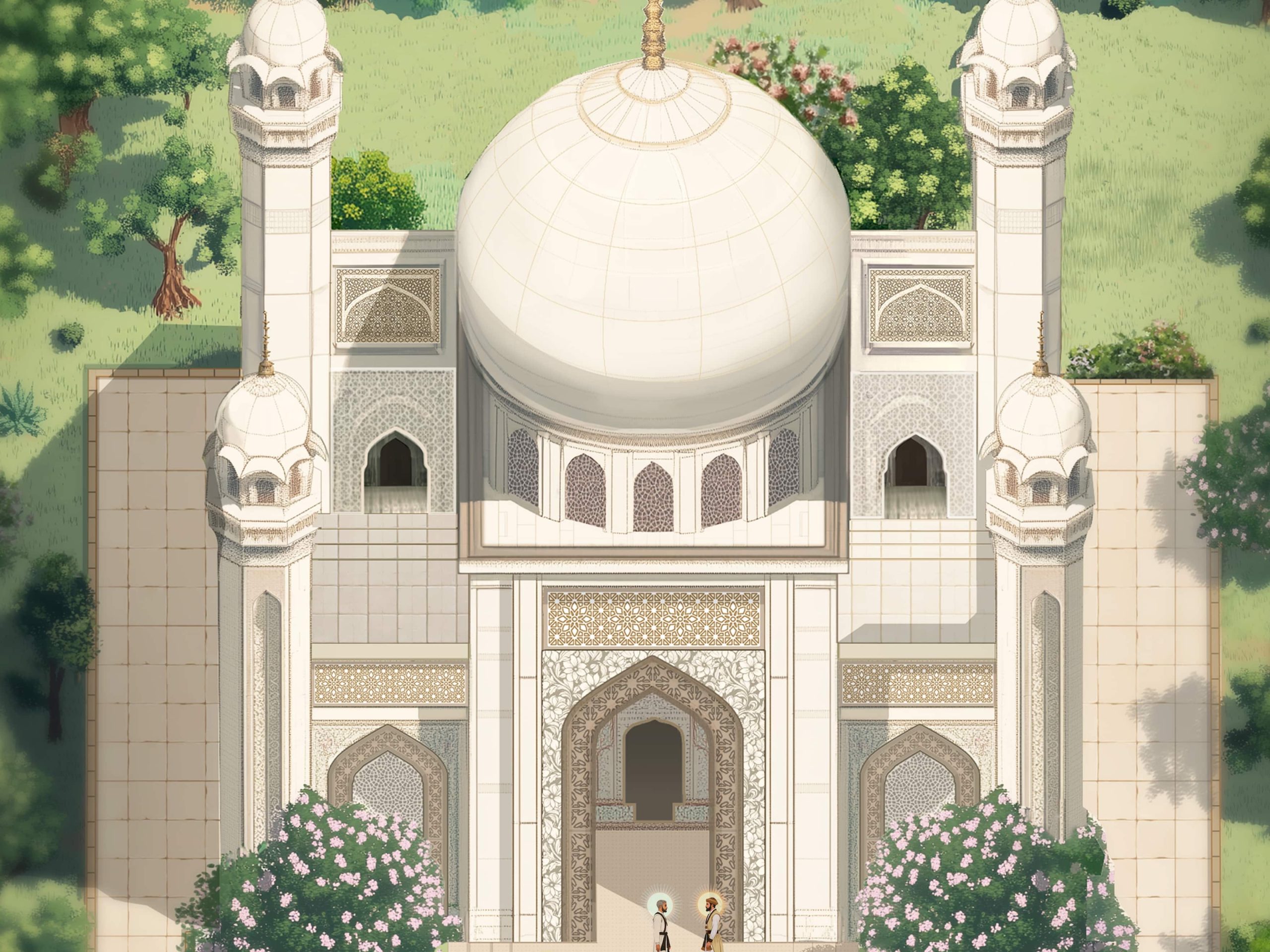

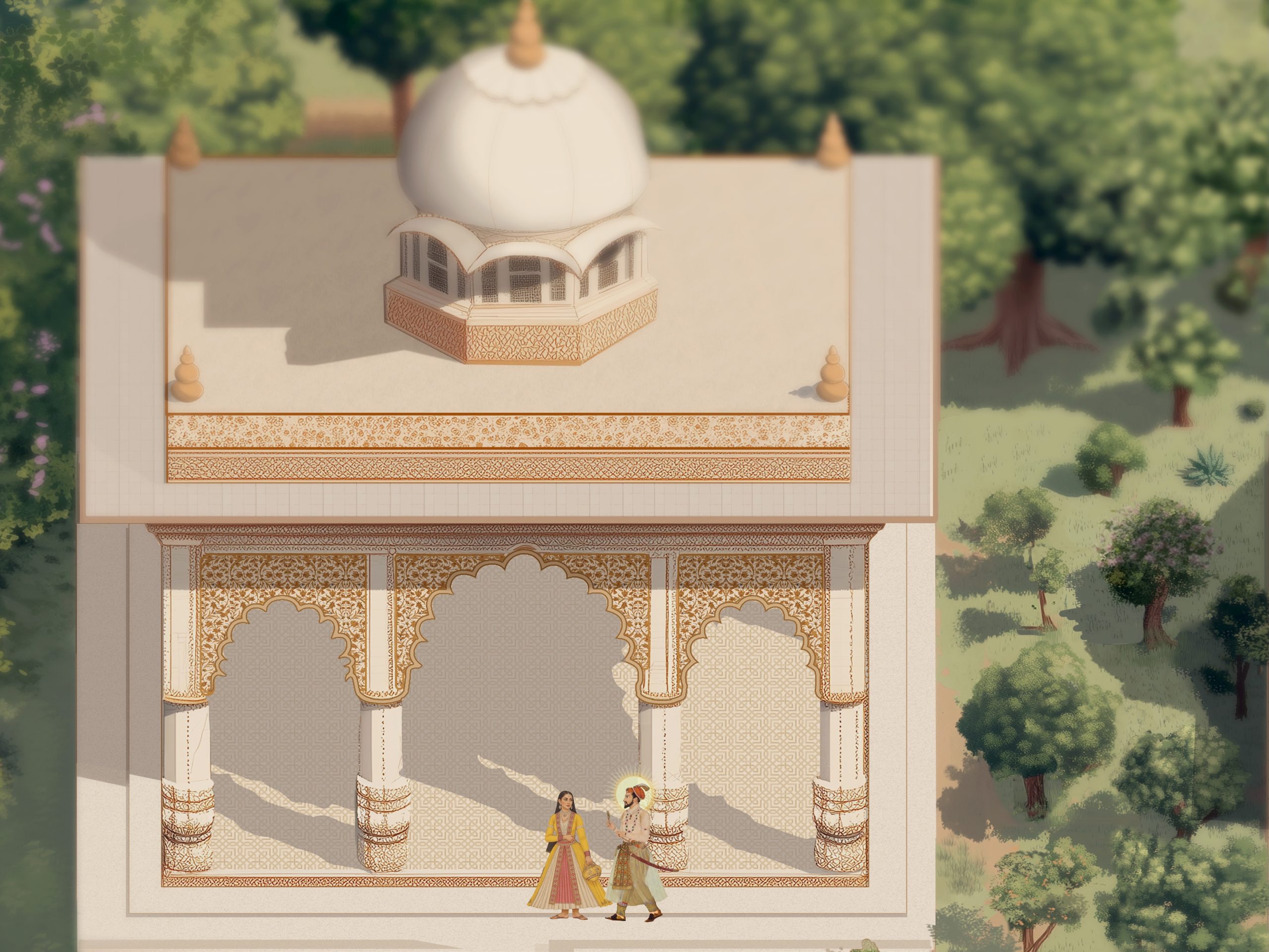

Created by Parag K. Mital and his studio, the Garden in the Machine, and commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through its Art + Technology program, The Game of Whispers is both a video game and a five-channel art video. Its story unfolds in the court of Shah Jahan, the Muslim ruler who built the Taj Mahal as a shrine to his favored wife, Empress Mumtaz Mahal. It focuses on the machinations of his youngest son, Prince Aurangzeb, who in real life rebelled after Shah Jahan named his eldest son, Prince Dara Shikoh, his heir apparent. In 1658, Prince Aurangzeb imprisoned their ailing father and went to war against his older brothers, Dara Shikoh chief among them. Ultimately Prince Aurangzeb captured Dara Shikoh, paraded him through Delhi in chains, had him murdered and sent his severed head to their father in a box.

At the heart of The Game of Whispers are non-player characters (NPCs)—game characters not controlled by players but by AI. These NPCs are driven by advanced large language models like those powering ChatGPT, allowing them to engage in lifelike conversations that create new layers of intrigue and deepen the cycle of disinformation. As the characters spread rumors and react to what other characters are doing, viewers witness how a single falsehood can ripple through the palace, influencing decisions and relationships.

The artwork also speaks to India’s current political climate, where differing narratives about the Mughal period continue to drive tensions between Hindus and Muslims. The Game of Whispers highlights how history too can be twisted to serve competing ideologies. In doing so, the work invites reflection on the fragile nature of truth in the past as well as in our AI-driven present.

Using images from Mughal miniatures, Mital’s team built animated characters and inserted them into the game world.

Visually The Game of Whispers presents a richly detailed, 2D world modeled after historical collections of Mughal miniatures, primarily that of LACMA, which co-organized the project with the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa, where it was first exhibited. Within this simulated environment, audiences follow the interconnected storylines of five NPCs. The technology powering The Game of Whispers is one-of-a-kind, developed by the Garden in the Machine for crafting and bringing autonomous characters to life inside games. The avatars are imbued with unique personalities, engage in lifelike conversations, and independently navigate their digital worlds. Each time a simulation or a game starts, an entirely unique unfolding of events occurs, due to the probabilistic nature of AI models.

Parag K. Mital, Ph.D., is an Indian-American artist and interdisciplinary researcher at the forefront of computational arts and machine learning. Based in Los Angeles, Mital lectures at UCLA’s Design Media Arts department and directs the Garden in the Machine, a creative studio specializing in AI and machine learning. His scientific background includes machine learning, deep learning, film cognition, eye-tracking studies, EEG and fMRI research. His artistic practice spans generative film, augmented reality hallucinations and AI-powered storytelling, tackling questions of identity, memory, and the nature of perception. He has also taught, primarily on computational arts and machine learning, at the University of Edinburgh; Goldsmiths, University of London (where he received his Ph.D. in arts and computational technologies in 2014); Dartmouth College; California Institute of the Arts, and the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bengaluru. He has collaborated with the likes of Massive Attack, Sigur Rós, David Lynch, Es Devlin and Refik Anadol. Among the projects he has contributed to is Anadol’s WDCH Dreams, a Columbia DSL Breakthrough Prize winner in 2019.

Parag K. Mital, Ph.D., is an Indian-American artist and interdisciplinary researcher at the forefront of computational arts and machine learning. Based in Los Angeles, Mital lectures at UCLA’s Design Media Arts department and directs the Garden in the Machine, a creative studio specializing in AI and machine learning. His scientific background includes machine learning, deep learning, film cognition, eye-tracking studies, EEG and fMRI research. His artistic practice spans generative film, augmented reality hallucinations and AI-powered storytelling, tackling questions of identity, memory, and the nature of perception. He has also taught, primarily on computational arts and machine learning, at the University of Edinburgh; Goldsmiths, University of London (where he received his Ph.D. in arts and computational technologies in 2014); Dartmouth College; California Institute of the Arts, and the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bengaluru. He has collaborated with the likes of Massive Attack, Sigur Rós, David Lynch, Es Devlin and Refik Anadol. Among the projects he has contributed to is Anadol’s WDCH Dreams, a Columbia DSL Breakthrough Prize winner in 2019.

Q&A WITH PARAG K. MITAL

This interview was conducted via videoconference by Columbia DSL awards director Frank Rose in March 2025. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Frank Rose: One thing I’m curious about is — this game is based on real people, historical figures, and I’m just wondering how closely you hewed to the historical record.

Parag K. Mital: Good question. There’s a lot of debate on how to even characterize the Mughal empire — what’s happening in present-day India, for instance, with the rise of nationalism painting the picture of the Mughal court as this very murderous empire. So it was really important for me to have an unbiased view of just how to even portray the characters.

That’s really where the authorship lies in the work, in the prompting of each character and defining who they are and their motivations, their beliefs, their desires. There was obviously some creative license there that I had to take, like Prince Dara Shikoh represents this voice of pluralism and mysticism and is opposed to his orthodox and power-hungry brother. So that narrative is based on my read of history, but I’m sure that’s a very contentious one, depending on who you ask.

Frank: Is this set at a particular moment?

Parag: It’s set during the time of Shah Jahan’s reign. He was the fifth Mughal emperor, 17th century. There wasn’t ever a peaceful transfer of power. Dara is the eldest prince. His younger brother Aurangzeb is the power-hungry, orthodox figure who has his father imprisoned and his brother supposedly murdered.

Frank: But Prince Dara’s brother was quite religious.

Parag: Very much so. He represented this orthodox tradition of Islam and opposed his brother, who was translating Hindu texts into Persian and trying to bridge this gap between the two faiths. Aurangzeb even played music, he played a type of stringed instrument, but music was banned after his rise to power under the orthodox Islamic rule he imposed. So their struggle for power represents this fracture in India’s past that we’re seeing play out again with the rising tide of nationalism in India.

Frank: You mentioned the narrative of the Mughal court being very violent. But at least in this instance it does seem to have been very violent.

Parag: My role in this work is to have people ask questions and leave with more questions than answers. I’m not trying to say what’s true or not. I’m trying to point out that who gets to decide what’s true is in the hands of who’s in power.

Frank: How did you get the idea for this project?

Parag: I had been reading a lot about the Mughal Empire and what’s happening in present-day India with the fracturing of Hindu-Muslim relations. And I had been listening to the Empire podcast by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand and learning more about India’s history. The project is meant to act as a mirror for what’s happening. I was drawn to this moment in history because its contradictions — the cultural flourishing on one hand and this power struggle on the other — really act as a mirror for present-day political climates, especially in India, where we see these historical narratives playing out in real time. AI is like a metaphor for how these narratives evolve and how someone can manipulate and manufacture a consensus of thought.

Frank: How do you mean, a metaphor?

Parag: This isn’t an authored story. We’re actually seeing AI in the story as these non-player characters that embody different individuals. There’s a time where Hakim for instance, another character in the story, is plotting how to cover up the crime of a death. AI is able to manipulate the rest of the characters in the story and say that, oh, he was ill and that’s why he died. This is exactly what we see happen on a large scale — for instance, in social media — in order to manufacture consent. One of the main differences being that this would’ve been a relatively tight, closed circle, whereas now it plays out with hundreds of millions of people.

Frank: What is the underlying technology here — the game engine, the language models you’re using?

Parag: The technology was all developed by the Garden in the Machine, which is my artist studio. We’ve been working on this technology now for about two years. We’re utilizing OpenAI’s GPT model, but it could just as easily be any other model. The technology allows us to effectively author these agents and test the interactions between them. We’re able to stream the agents to Unreal Engine, which is the game engine we’re using to build the world. Unreal Engine has this plugin that makes building 2D animations quite easy. And 2D fits so well with the aesthetic of the miniature paintings. I wanted it to feel and look like a crossover of miniature paintings with this game-like aesthetic of an early Final Fantasy kind of world. But everything is powered by this in-house, custom technology that we’ve been working on for about two years, which we call internally Endless Forms.

Frank: What’s your background? You’re Indian-American, obviously, but were you born here or in India?

Parag: I was born in the US. My parents were born in Uttar Pradesh, where the Taj Mahal is. They raised me Hindu, but I am not a practicing Hindu. I am much more, I would say, mystical or spiritual. I grew up in a small town in Delaware and came to LA through a long, convoluted route that took me to Copenhagen, to Amsterdam, to Scotland, where I did my master’s and then worked in the uni for two years as a cognitive scientist, and then I did my Ph.D. in London. Then I ended up traveling the world for a year. Did my postdoc at Dartmouth and then eventually drove cross-country to LA. I have many friends in India but I’m not living in India, so I can’t speak directly to what it’s like being there.

Frank: But you’ve gone there a number of times.

Parag: Absolutely. And the work even premiered in India.

Frank: How did that come about?

Parag: LACMA worked with the Serendipity Festival, an incredible arts festival now over 10 years running in the city of Panjim. They do a brilliant job of making the entire city feel like a festival.

Frank: The festival was in December. When did you start working on it?

Parag: It was about two and a half months, three months max. Prior to that we’d gone through a couple iterations of ideas. And this was the only one that I was like, I know it has to be this one, but it’s such a crazy idea and it’s gonna be so difficult. But I just couldn’t not do it at that point. Once I had the idea, I was like, okay, this is gonna be impossible, but we’re gonna figure it out. And we did. It’s got the historical lens, which LACMA as a museum has, this incredible collection that would love to see the light of day, I’m sure. And now we have this narrative vehicle that I think acts as this really modern lens on society at that time.

Frank: Did Joel [Ferree, director of LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab] suggest India?

Parag: No, it wasn’t that it had to be about India, but the work would premier in India and that was the link for me. I wanted to speak to current political climates and I had to make use of their collection as well, and it all just gelled.

The five main characters in The Game of Whispers are Javed, a gardener; Khadija Banu, a confidante; Empress Muntaz Mahal; Prince Dara Shikoh, and his nemesis, Prince Aurangzeb.

Frank: Had you worked with LACMA before?

Parag: I think they were somehow familiar with me. Joel reached out to me and was saying like, how have we not worked together? He was curious if I had any ideas for working with their collection and presenting the work in India. I knew it had to speak to the current political climate. It had to be critical of the use of AI and misinformation. Then I saw in their collection these incredible miniature paintings from the Mughal Empire. And I thought how great it would be to tell this story through the lens of AI. So it all came together quite quickly.

Frank: The NPCs — are they based on miniatures from the LACMA collection?

Parag: They are. There’s three in particular that are directly taken from their collection. The rest are a process of AI generation and hand-drawn illustration.

Frank: Tell me a bit more about the journey from the nascent idea to how you developed it over the course of two or three months.

Parag: It’s kind of an extension of my previous work. The underlying technology is something I’d been developing, like exploring agents and building language models inside of game engines. It’s also heavily inspired by John von Neumann, who in the ’40s was developing these ideas that would become instrumental in game theory and geopolitics. Von Neumann was this inflection point of history for me, because he helped shape how we simulate conflict in terms of nuclear war and disarmament and geopolitics. Also by John Conway’s Game of Life, which explored how complex behavior emerges from simple rules. In The Game of Whispers we have agents acting as narrative automata — they are not just moving, they’re reproducing ideas, they’re mutating stories into disinformation. And we’re seeing how perception shifts over time.

Frank: What was the experience of people at the festival?

Parag: I thought it was incredible. It was such a challenging work to pull off, first of all. During that festival, so many different people of all ages, of all backgrounds, very diverse types of people with very different interests in the work, like what AI can do in terms of misinformation. Some people were fascinated with how AI could so easily spread misinformation and change the narrative. Some people were really interested in the illustrations, or more interested in the architecture.

I was personally very aware of the fact that I’m not from India, coming in as a Westerner speaking to the current political climate, how that is also a form of colonialism. I didn’t want to impart my own bias into this story, but obviously it will be there. And part of what I had written was that AI has a role in adding to political tensions between Hindu and Muslim societies in India. That is a fairly contentious statement, and somebody called me out for it there. Somebody who had come to see the work was visibly quite angry. I tried to just explain, for me, I feel that AI’s role is in exacerbating this sort of tension between the two societies, and we’re seeing the role of disinformation play out in real time and how AI is able to amplify that. And then by the end of it he was like, “Oh, this is very important work.” I was so surprised—I thought he was really mad.

Frank: Can you tell me more about your sense of what’s going on today and how it translates to the period of the game?

Parag: We’re seeing Mughal history being rewritten to stoke nationalist ideologies. We’re seeing the death of pluralism and this rising orthodoxy rooted in nationalism, and that is a vehicle for power. It’s a narrative that’s been played out time and time again in history. It’s very successful. Somehow we’re just drawn to this. It’s talking about the Mughal court, but really it’s a mirror for present-day society and AI being able to manufacture ideas, facts, non-facts, misinformation at scale. We were doing that plenty fine without AI, but now we’re able to do it on the scale of society and not even really know who the players are, like who’s buying our attention and who’s doing what.

Frank: Were you inspired, so to speak, by the political situation here in the US as well?

Parag: Yes, absolutely. We’re seeing systems of narrative power being the influence on what we call democracy in this country. It’s really who tells the better story.