Network Effect: Human Life on the Internet

“Staring at a glowing rectangle is no way to live.” —Jonathan Harris

A network effect is the halo that results when each new user of a given service—the telephone, for example, or Facebook—inadvertently makes the service more valuable to others simply by joining it. But is this kind of value creation necessarily a good thing? Network Effect, which made its debut online in October 2015, suggests that it may not be. “Once people come in, then the network effect kicks in and there’s an overload of content,” Greg Hochmuth, a software engineer who helped build Instagram, told The New York Times. “People click around. There’s always another hashtag to click on. Then it takes on its own life, like an organism, and people can become obsessive.”

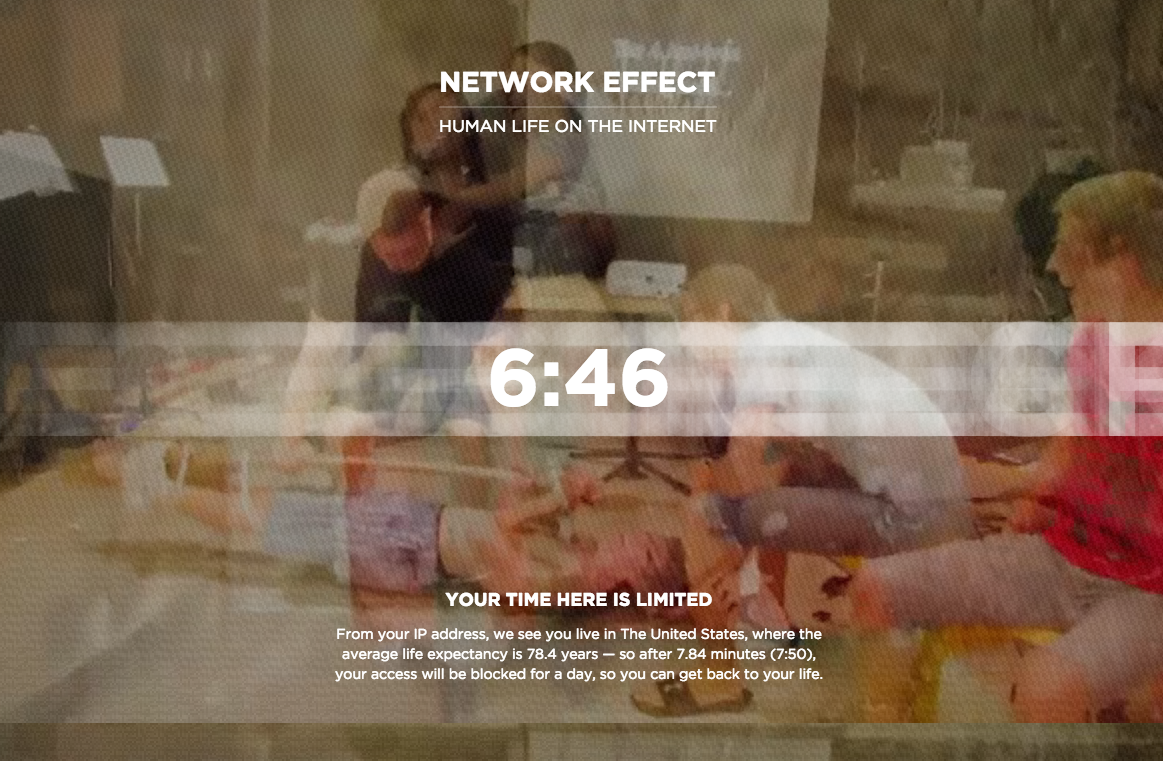

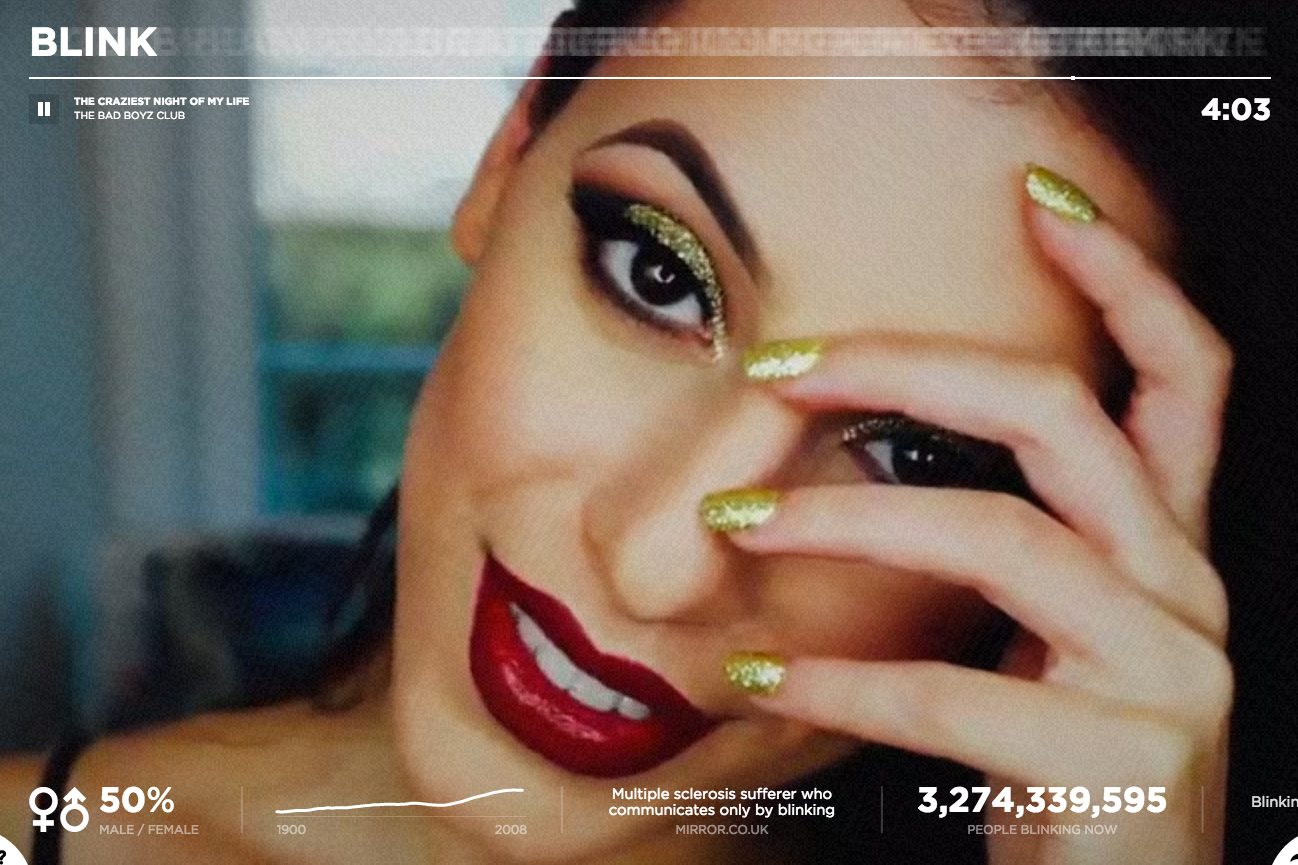

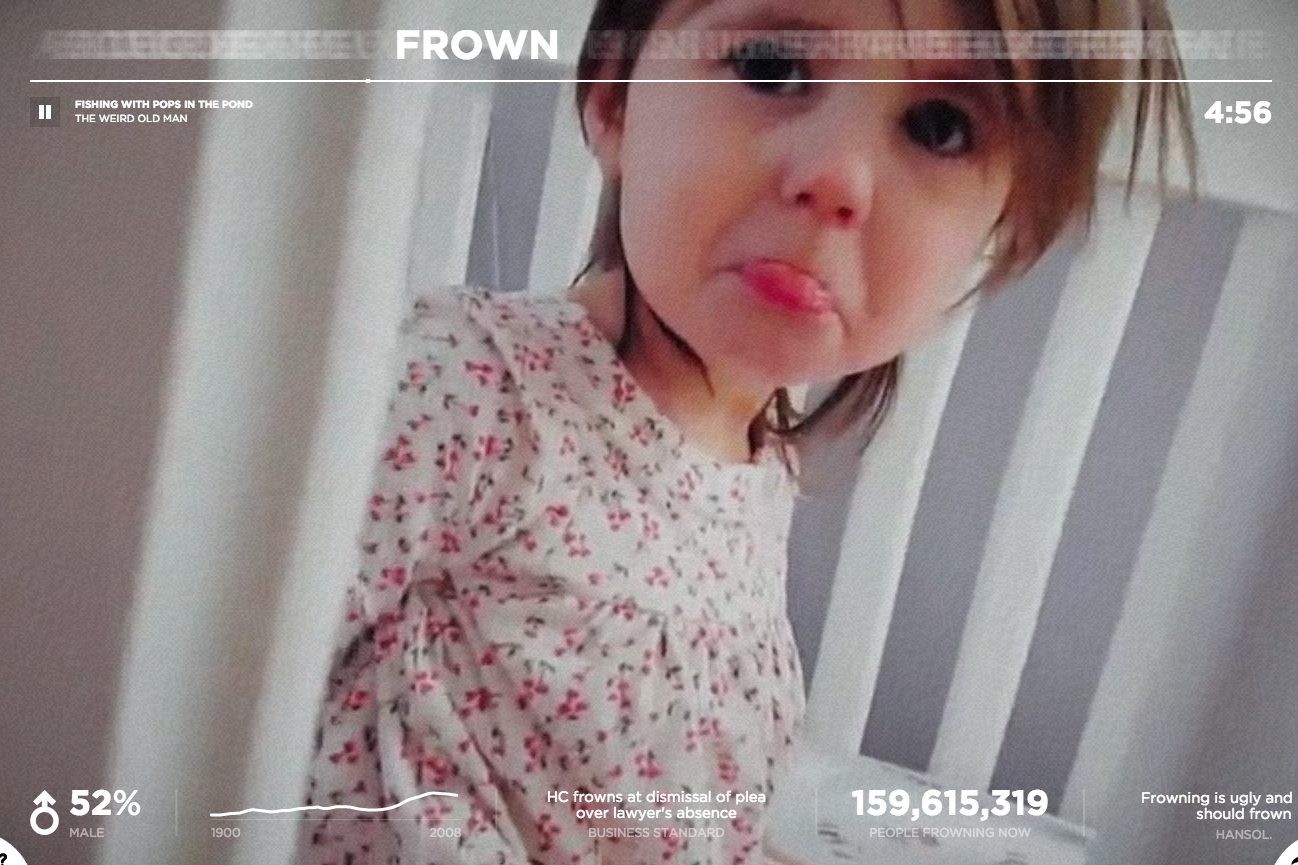

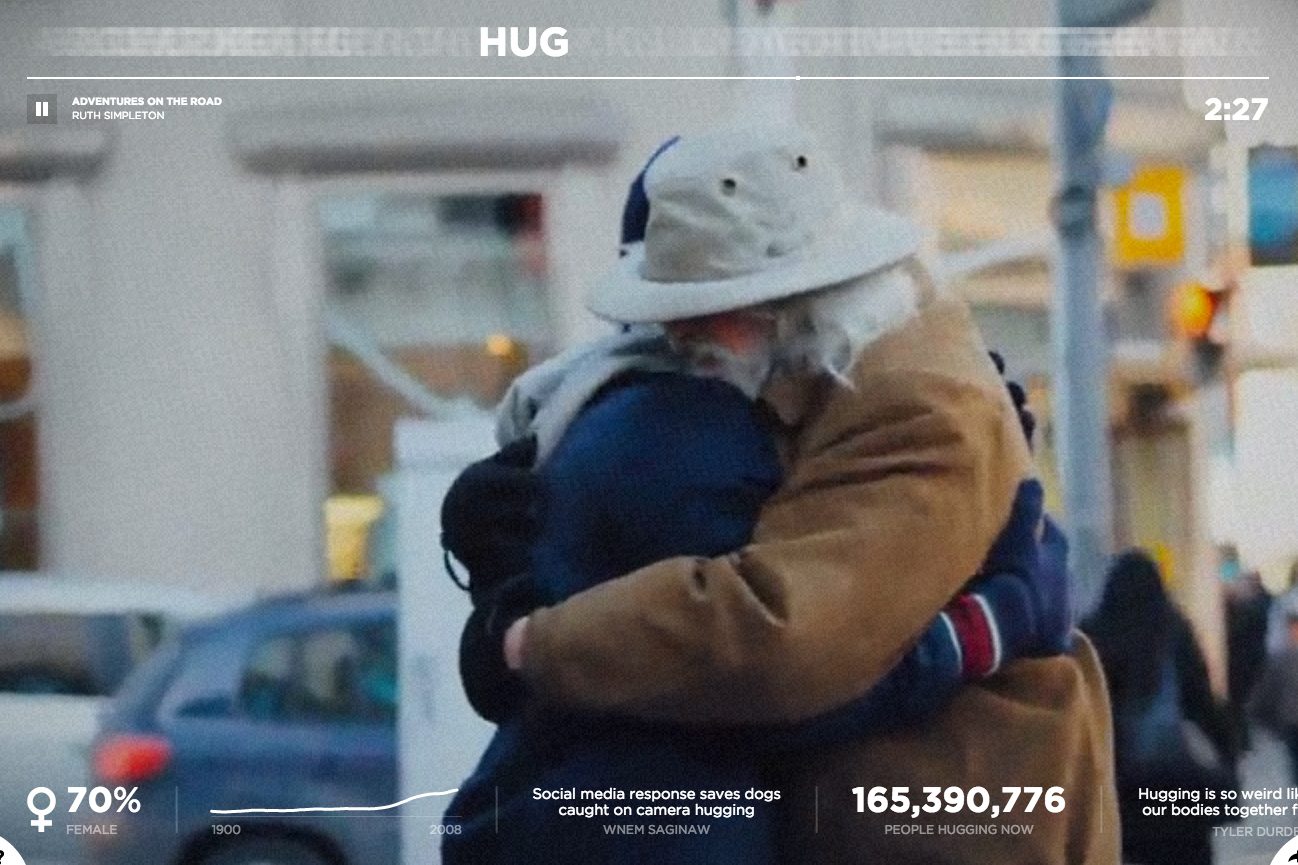

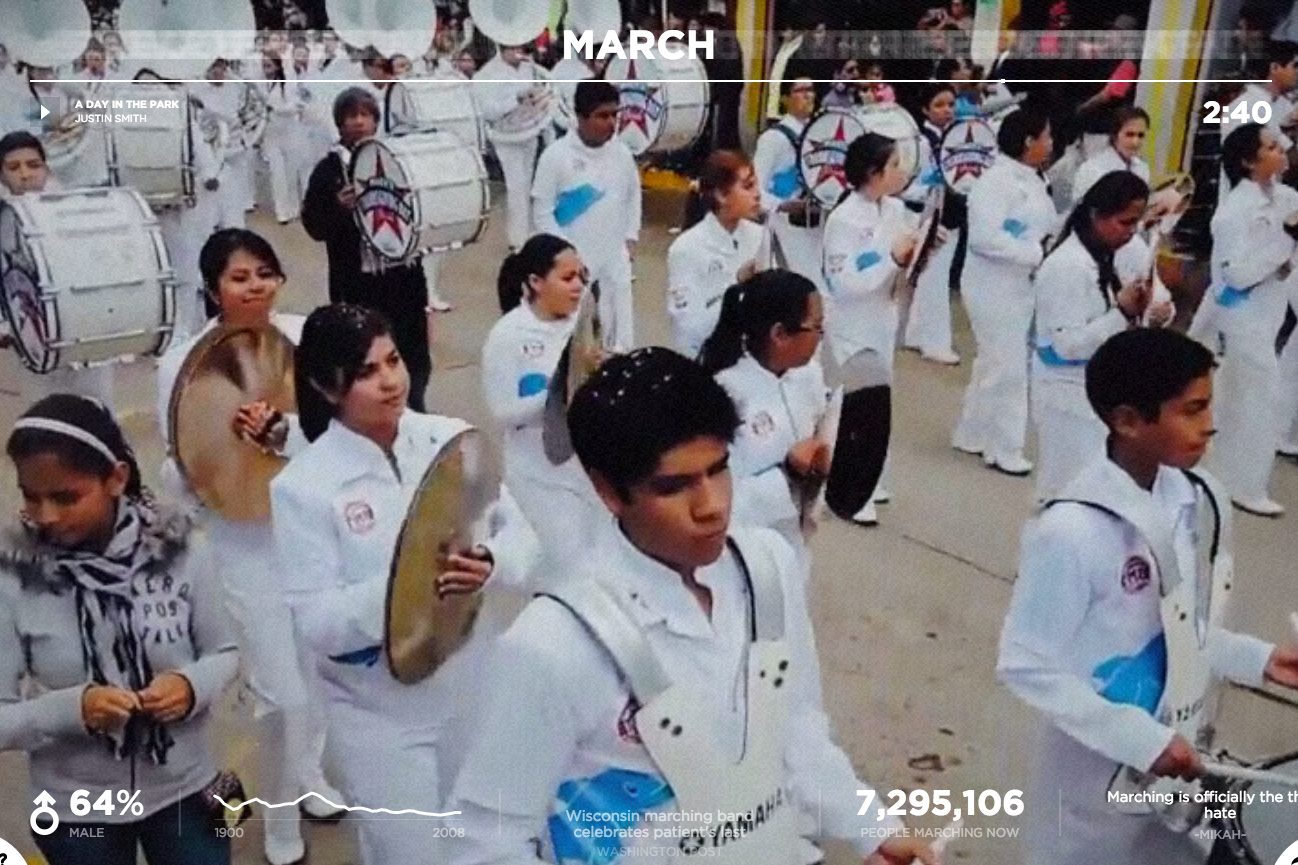

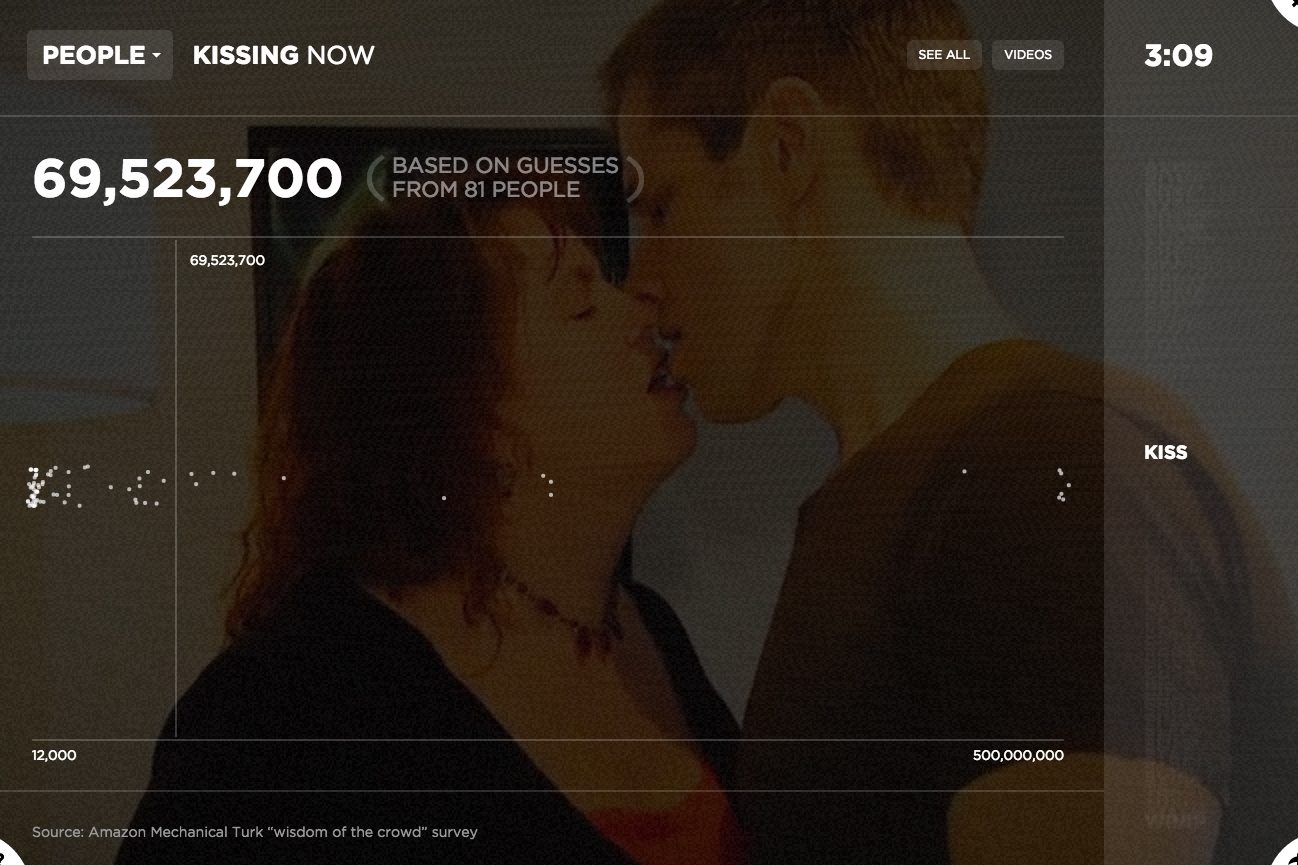

To explore the consequences of this kind of behavior, Hochmuth and Jonathan Harris collected 10,000 YouTube snippets of people doing ordinary things—yawning, eating, falling, cuddling, 100 different actions in all. These were then trimmed, cropped, processed, sped up, layered with voice-overs, set to the sound of a human heartbeat, and transmuted into a stream of frenetic, anxiety-provoking activity. Users are not permitted to see the whole thing at once. Instead they see a message like this:

From your IP address, we see you live in The United States, where the average life expectancy is 78.4 years — so after 7.84 minutes (7:50), your access will be blocked for a day, so you can get back to your life.

Jonathan Harris (born 1979 in Vermont) studied computer science at Princeton University and interactive art at Fabrica, the communications research center in northern Italy. His early data visualization projects explored the ways in which the human species was evolving into a single planetary “meta-organism,” which could be probed and represented through the troves of Internet data that it was producing. In 2007 he shifted back to the physical world through a series of experimental documentary projects that helped establish the field of interactive storytelling even as they explored the ambiguous relationship between humans and technology. In 2009, when he turned 30, he began to document his own life experience by taking a photograph and writing a short story each day and posting them online each night before going to sleep. He continued this daily ritual for 440 days.

Jonathan Harris (born 1979 in Vermont) studied computer science at Princeton University and interactive art at Fabrica, the communications research center in northern Italy. His early data visualization projects explored the ways in which the human species was evolving into a single planetary “meta-organism,” which could be probed and represented through the troves of Internet data that it was producing. In 2007 he shifted back to the physical world through a series of experimental documentary projects that helped establish the field of interactive storytelling even as they explored the ambiguous relationship between humans and technology. In 2009, when he turned 30, he began to document his own life experience by taking a photograph and writing a short story each day and posting them online each night before going to sleep. He continued this daily ritual for 440 days.

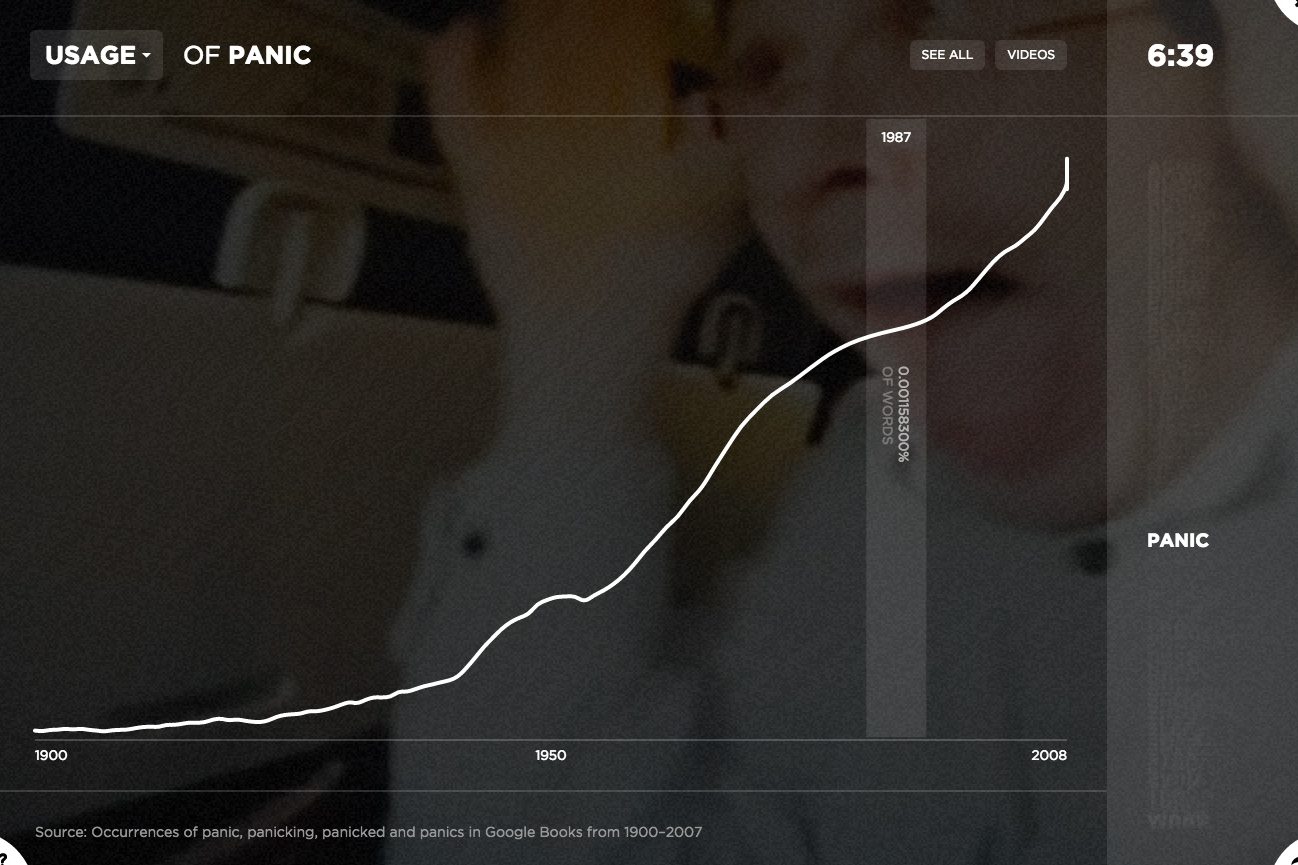

This evolved into Cowbird, a free (and ad-free) storytelling platform for anyone to use, providing a more contemplative alternative to existing social media environments. Time magazine named it one of the 50 best websites of 2012. But as our collective relationship with the Internet began to change from one of utopian possibility to one of attention economies, fake news, filter bubbles, and widespread screen addiction, Harris decided to close Cowbird after five years of operation, leaving it online as an historical archive. In 2012 he published “Modern Medicine,” an essay comparing software to a new kind of drug. This dawning ambivalence about the medium he had been using for more than a decade produced a difficult period of creative block. Then, in 2015, he and Greg Hochmuth produced Network Effect, which used the aesthetics of data visualization to question the ultimate utility of data — and to gesture at what might lie beyond it.

In early 2016, following the death of his mother, Harris returned to his family’s land on the shores of Lake Champlain in Shelburne, Vermont. There he has been living and working since as a steward of High Acres Farm, part of the 3,800-acre estate assembled between 1886 and 1902 by his great-great grandparents, railway executive Seward Webb and Eliza Vanderbilt Webb, an heiress to the Vanderbilt fortune. Under the direction of Harris, his sister and their cousin, High Acres Farm is evolving into a creative center for human culture and the natural world.

Greg Hochmuth is an artist and engineer specializing in data science. He studied computer science and design at Stanford University, then worked as a product manager at Google, focusing on Chrome, Translate, and ad personalization. He left Google to join Instagram as employee number seven, and remained with that team through its acquisition by Facebook, working as an engineer, product manager and data analyst. He left Instagram to move to New York, where he has worked on a variety of creative and technical projects.

Greg Hochmuth is an artist and engineer specializing in data science. He studied computer science and design at Stanford University, then worked as a product manager at Google, focusing on Chrome, Translate, and ad personalization. He left Google to join Instagram as employee number seven, and remained with that team through its acquisition by Facebook, working as an engineer, product manager and data analyst. He left Instagram to move to New York, where he has worked on a variety of creative and technical projects.

In April 2016, Network Effect received the 2016 Infinity Award in New Media from the International Center of Photography. It has been featured at the Beijing Media Art Biennial, the Sónar Festival Reykjavik in Iceland, Tribeca Film Festival’s Storyscapes, IDFA DocLab in Amsterdam, PopTech in Camden, Maine and numerous other venues.

“‘We had this idea that we’d create an empathetic human library of everything we do, that people could see themselves in,’ Hochmuth said. ‘But when we put it in the interface, it never felt warm. . . . It was honestly kind of sad. . . .’

“Harris had been the Internet’s evangelist and its portraitist; he’d lived inside it and away from it. Over breakfast in New York, he and Hochmuch decided to upend the direction of their project: It would be the Internet’s final judgment.”

“‘The idea for this came from the idea of an alien species coming to earth and observing the human species,’ Harris explains. ‘What would it see? All the strange behaviors that human bodies do. . . .’

“It’s hours of content to dig through, and yet, you’re only given a few minutes – a small fraction of your life expectancy, which is calculated by the location of your IP address – to view the site before it locks you out. There isn’t enough time to make sense of the perfectly organized cacophony, and as a heartbeat ticks down the seconds you have left before the page goes dark, you’re reminded of your own mortality, and more accurately, all of the moments you’re constantly wasting online.

“‘There is a voyeuristic and titillating quality to this experience, but it is also deeply empty,’ Harris says. ‘We do not go away happier, more nourished, and wiser, but ever more anxious, distracted, and numb. We hope to find ourselves, but instead we forget who we are, falling into an opium haze of addiction with every click and swipe.’

“Indeed, as soon as ‘Network Effect’ locked me out, I hopped into an incognito browser to try it again.”