The Horrifically Real VIrtuality

The Horrifically Real Virtuality summons the ghosts of Ed Wood Jr. (allegedly the worst movie director of all time) and ageing B-movie legend Bela Lugosi (the first-ever on-screen Dracula) as they reunite to shoot their final masterpiece. It stars Lugosi as a character who can access a parallel dimension called Real Virtuality, where he encounters humanoids from another time — the audience. Audience members are invited both to visit the set and to watch the screening of Ed Wood’s latest film — a movie so scary that they might just . . . get sucked in!

But the shoot is obviously a disaster. The low-budget production is way off-schedule, the set is in chaos, the production team is overrun and the lead actor stays in character 24 hours a day. The audience is going to have to do some serious multi-tasking: operating the camera and special effects, taking over as sound engineer, open inter-dimensional doors by the use of the energy of lightning, chasing away flying saucers and even standing in as extras. Above all, they must never forget the first rule of B-movie horror: NEVER ANSWER THE PHONE.

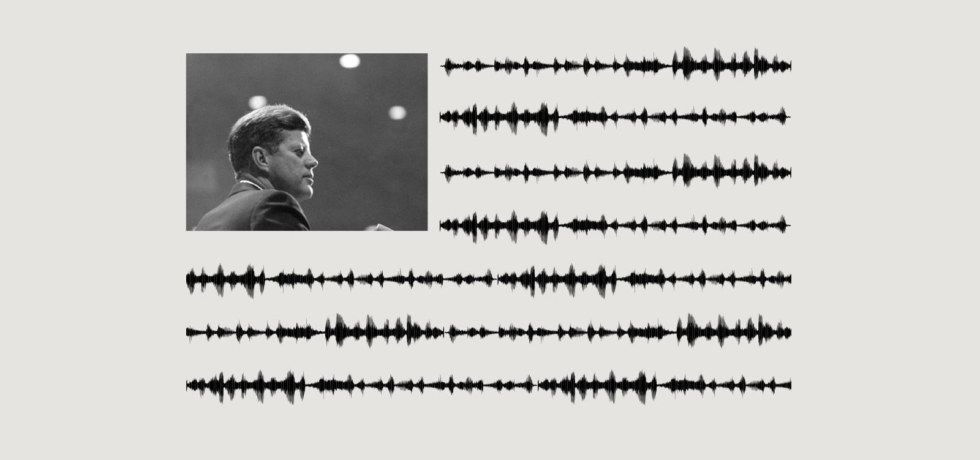

The Horrifically Real Virtuality is an immersive 50-minute theatrical and collective experience combining virtual reality, acting and cinema. It prompts audiences to interact with live actors in both real and virtual environments. The narrative is full of references to the early days of cinema, while the grotesque special effects deliberately contrast with the cutting-edge cross-reality technologies involved. Throughout the experience, hidden mechanisms are openly revealed, front and back stage overlap, story and staging merge, creating a new dimension halfway between the real and the virtual: the illusion of the false.

—Marie Jourdren, DVgroup

ASK THE CREATOR

Why this? Why now?

Marie Jourdren: About Ed Wood — so many analogies can be found between Ed Wood and virtual reality that he could easily be an icon for the world of VR. While struggling to find funding for his films, Ed Wood puts together low-budget productions, developing a strong sense of ingenuity. The result inevitably suffers: an editing resulting in an absurd narration, a film crew often “multitasking,” and despite everything, a faith and a frenzied optimism. As for the topics covered, if Ed Wood has scoured the stories of vampires and extraterrestrials, we can observe that VR has not been left out so far with fear-driven topics, often on hospitals, prisons, ghosts and such.

Nevertheless, there is an almost childish joy and enthusiasm in Ed Wood’s desire to deceive the senses. His films are full of special effects, stage riggings, and as clumsy as they might be, they convey a strong will to delude, in an artisanal way, like fairground entertainers used to. It is also this desire that we find among the VR creators today: being able to, through these technologies which allow us to create illusions, teleport the spectator elsewhere, to immerse him in other universes where the laws of physics don’t have to exist. We all share the crazy desire of experimenting. If Ed Wood was an unfortunate representative of the mediocrity of what special effects can be, VR might well be a renewal of the matter.

Usually considered as an offspring of the video gaming industry, fictional VR is still the poor stepchild of cinema, and struggles to earn consideration. Funding is always too thin, and filmmakers are still reluctant to explore this new media, for which they do not master the technologies. But if we must remember, the history of cinema begins with a train entering a station, enough for the first spectators to be frightened.

“If Ed Wood was an unfortunate representative of the mediocrity of what special effects can be, VR might well be a renewal of the matter.”

Ed Wood was on the edge of the Hollywood star system, just as the VR is still marginal to the cinema industry today. It is this friction, this reciprocal “sniffing” of cinema and VR that I want to tell in The Horrifically Real Virtuality. With tenderness and a lot of self-mockery.

Considered today as precious gems, Ed Wood’s movies are full of riggings and awkward special effects that fans of the genre love to analyze: the shadow of a stage assistant passing behind a sheet of scenery, clumsy-made models, puppet-like animated elements whose strings remain visible to the image. . . . Ed Wood’s films tell a story, but also — and unintentionally — their manufacture, where front and back stage seem to merge.

This process of superimposing the main subject and its staging places the spectator in an extremely enjoyable position, on the secret-knowing side, like a true accomplice of the director.

Thus the narrative and humorous mechanics of The Horrifically Real Virtuality were born and mainly rely on this paradox: to use the most advanced VR technologies in terms of illusion making, to reproduce the narrative clumsiness and the poor special effects of Ed Wood’s cinema.

About immersive VR theatre — When I created my previous VR play Alice, The Virtual Reality Play, I wanted to push the limits of what VR could offer further. While the landscape consisted mainly of 360-degree films, I had the intuition that we could push the immersion in a story much further by offering the audience a fully interactive universe. This meant that the audience had to be able to physically move around in a tangible space and leave their status as a ghost or omniscient audience member to actively participate in the narrative and interact with the characters in the story. Alice was the first immersive virtual reality play in the world, a unique format that superimposed physical and virtual set, in which the spectator and virtual characters played by actors (or “reactive actors”) evolve.

“The public is increasingly looking for ‘exotic’ experiences: strongly immersive, interactive, participative, sensory, and highly personalized. I am convinced that this new format, the immersive virtual reality theatre with live actors, brings all these together.”

The possibility for the audience to see their hands, as in Alice, or even their entire body represented as an avatar, as in The Horrifically Real Virtuality, as well as the possibility for the audience to move in spaces physically coherent with their visual representation considerably increases the feeling of “presence.” The more the universe in which the audience evolves seems credible to them, the more powerful their sensations and emotions will be. It is even the first time that an entertainment format can generate such a wide range of emotions in the audience. Whereas in cinema the spectator can feel very strong emotions through empathy with the protagonists of a film, in an immersive VR play the audience is in direct and physical reaction to their environment: their emotions and sensations belong intrinsically to them.

We note that the public is increasingly looking for “exotic” experiences: strongly immersive, interactive, participative, sensory, and highly personalized narrative shows. I am convinced that this new format, the immersive virtual reality theatre with live actors, brings together all these criteria.

Talking about the future, there are of course still many unknowns, as we are only at the very beginning, and it is still a question of setting up the codes, the grammar, and building the standards for the production and distribution of this new entertainment format. But I deeply believe that we are at the dawn of something revolutionary, which reminds me of the early days of cinema. The feeling of being a pioneer, a mad inventor at the same time, all this is really exciting.

Cinema street

Hollywood

Cemetery

Bela Lugosi's living room

What was the most challenging aspect of making this work?

MJ: We have faced many technical difficulties, since we have created a completely new entertainment format. We often had to mix technologies that were not intended to be. Creating our shows required a lot of research and development.

I want to give an example from our previous production Alice, The Virtual Reality Play. In the context of this story adapted from Lewis Carroll’s novel, it seemed obvious and unavoidable to me to bring the spectator to eat or drink during the experience (since in the book the foods Alice consumes all have extraordinary and magical properties). Getting the audience member to eat the Caterpillar fungus was a big challenge. First of all, it required a very fine calibration work, so that the virtual universe is superimposed as precisely as possible on the real physical universe, to ensure that the virtual mushroom is placed exactly where the physical mushroom is. Then, it required to make the audience be able to see their hand grab the mushroom, regardless of the hand with which they accomplish this action, or the way they do it (for example, if they pass the mushroom from their right hand to their left hand). It may seem silly, but it’s quite difficult to set up technically, and really essential not to break the audience’s immersion. Finally, the work also focused on the narrative, and almost even on behavioral psychology, because it seemed really difficult to push someone to ingest a food that they cannot see “in real life” but only in a virtual way. As if a stranger were asking you to blindfold yourself and eat what he was going to put in your mouth. However, it was finally a success: with a total of about 1000 performances, only one person refused to eat the mushroom! This very small portion of the experience alone was very rich in learnings for our whole team.

“I deeply believe that we are at the dawn of something revolutionary. The feeling of being a pioneer, a mad inventor at the same time, all this is really exciting.”

There are also many challenges for the actors. The first challenge is to perform while being equipped with specific recording devices. It consists mainly of a helmet equipped with a camera that records the actor’s facial expressions and trackers on the body to capture his body gestures. All this data is reapplied in real time to the avatar that the actor embodies. The second difficulty is to have to mentally imagine the virtual universe that the audience members visualize in their helmet. The actor is sometimes helped by a monitor installed on the set, but this only represents a limited field of view and a single point of view, whereas the experience can be multi-user. On the other hand, it is quite enjoyable for the actor to be able to overturn the situation in a certain way: traditionally in theatre, audience members can observe the actor, while the actor, lit by the lights on stage, cannot see the audience. In virtual reality, the actor is the only one who can really observe the audience, while they are only able to see him as an avatar. The actor may thus have a stronger impression of “control” over his audience.

The cross-reality experience is also very different from the classical theatre work. Traditionally, the set and technical devices are set up before the show, and the actor is alone on stage during the performance. On a cross-reality stage, many parties operate while the actor is acting: the ”ninja” (who moves the physical set elements and guarantees the safety of the viewers in their movements), the “hosts” (who equip the viewers with the VR equipment and check their load and proper functioning), the “backstage master” (in the control room, the developer who follows everything that happens in the virtual universe on the control screens and makes sure that everything goes well). While improvising with the audience, the actor must be in constant communication with the other members of the team. This requires a considerable effort of concentration.

Regarding the narrative writing, this involved a lot of exchanges and dialogue also between the creative team and the technical team. The work of each team had to constantly adapt to that of the other, to overcome the difficulties. Nevertheless, we have noticed on several occasions that the very strong technical constraints led us to much more creative solutions than those initially envisaged!