Where There’s Smoke

Dedicated to

Robert Douglas Weiler

1939 – 2018

“When my Dad was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer we experienced a lack of empathy within his care that was so profound it became the inciting incident to an amazing and heartbreaking journey. Over the final year of his life we collaborated on what would become Where There‘s Smoke.

Where There‘s Smoke has always been difficult to classify. The project explores grief, memory and loss. When my Dad was diagnosed we became obsessed with finding a cure — we wanted an answer. Instead each step of the process only raised more questions. At every turn my Dad’s choices became more and more limited until none remained and he had to let go.”

— Lance Weiler

Two Journeys

By Lance Weiler

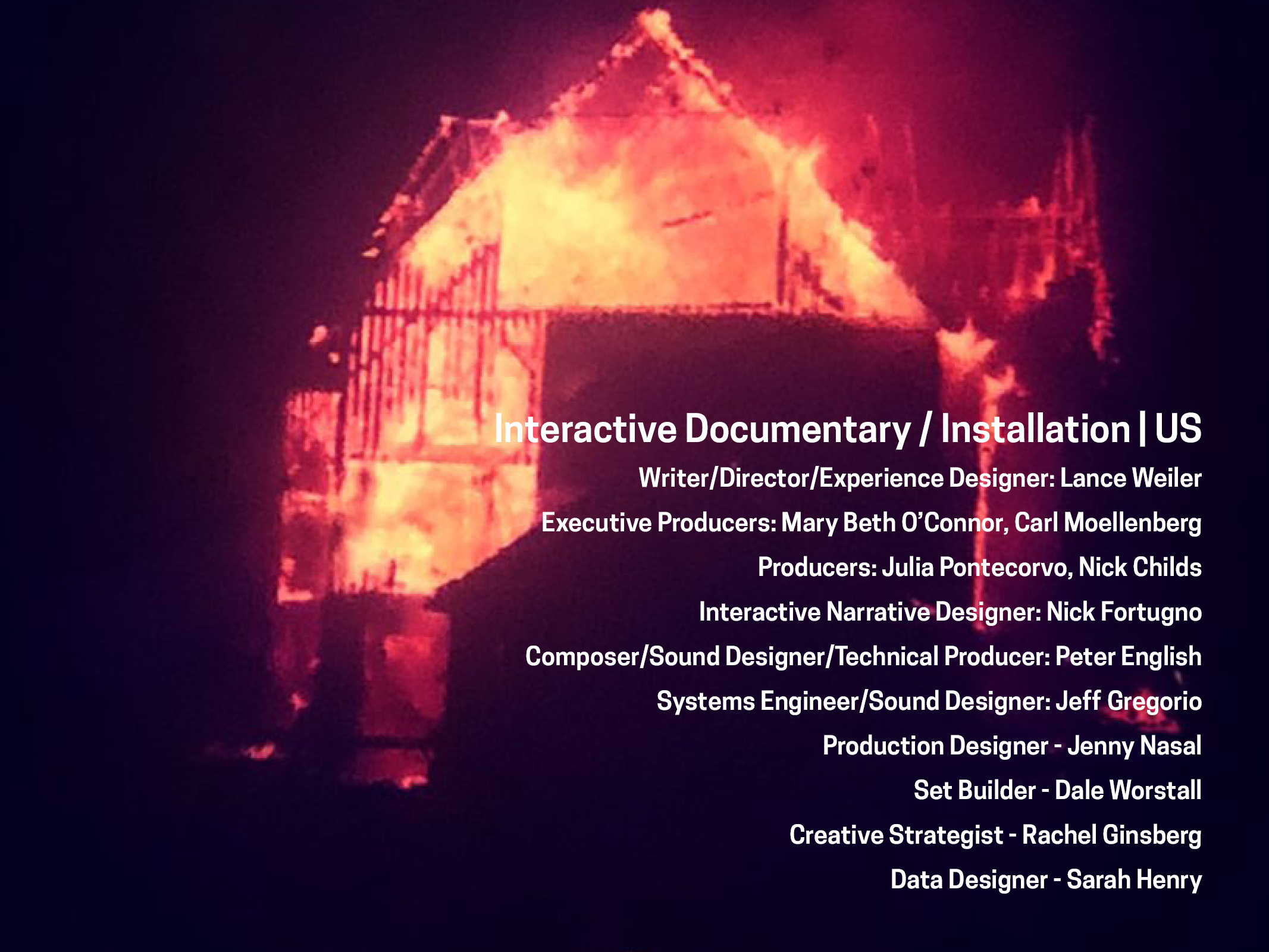

Where There’s Smoke mixes documentary and immersive theatre with elements of an escape room to explore memory and loss. Set within the aftermath of a blaze, participants work to determine the cause of a tragic fire by sifting through the charred remains.The Participant Journey

In April 2019, when Where There’s Smoke had its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, it was staged in a nearby storefront on Canal Street in lower Manhattan. Participants experienced it in groups of four. On entering the space, they went through a visualization exercise that placed them within a burning structure. After closing their eyes, they were asked to save the one thing they are emotionally connected to. Then they drew the object they saved on an index card, exchanged cards with a partner and interviewed each other by asking a single question five times in a row: Why are you emotionally connected to this object? Afterwards, all four participants were invited to explore a box containing artifacts that once belonged to my Dad. There they found a flashlight, a map and a special letter.

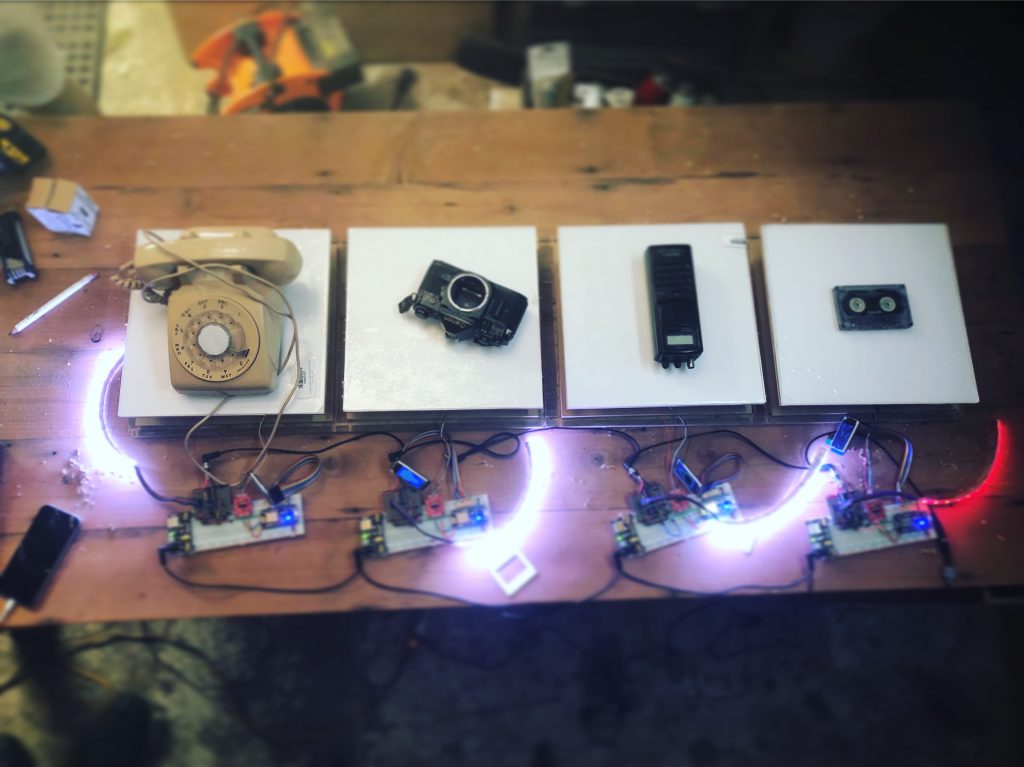

Next, the participants went through a door and into a dark, fire-damaged hallway. There was a strong smoke odor. At the end of the hallway they discovered a hole in the wall leading to a room filled with things from my childhood home. Within the room, set against visuals curated from thousands of slides my Dad shot as a volunteer firefighter and amateur fire-scene photographer, were four “enchanted objects”—a 35mm camera, a cassette tape, a walkie talkie, a rotary phone—that belonged to my Dad. When they found all four objects and picked them up, the room changed state. A table in the center of the room activated and lit up. Participants were prompted to place the objects on a series of light tables nested within the table. That unlocked a series of story fragments that were projected onto the wall by an old slide projector. There are nine possible fragments that can be unlocked. However, participants will only see four within the 45 minute experience. This means that each experience is different.

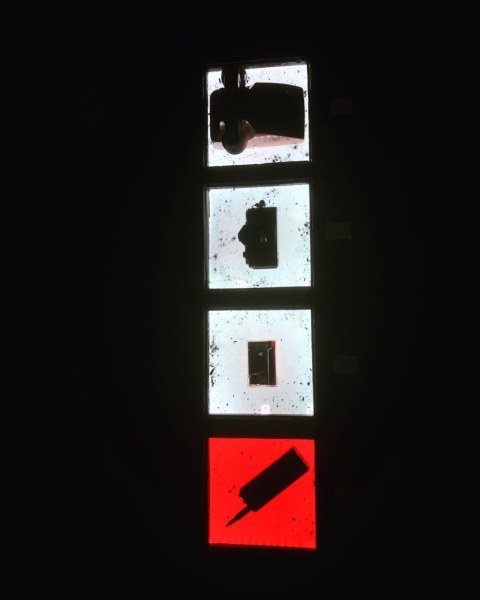

After unlocking the fourth story fragment, participants are prompted to select the object they feel holds the most emotional significance within the stories they have just witnessed. Once the object is selected, the room knows and releases a story related to it. Participants then move to a debriefing room that is washed in dim blue light. They are asked to share the objects they each saved during the onboarding phase of the experience. The room becomes an archive of emotional artifacts, each containing a story. In the final beat of the experience, the participants open the letter they found in the box during the onboarding phase. They learn that my Dad was collaborating on the project and was excited for others to experience it. The participants exit into a long hallway that leads them to a light panel of slides and a sign. The experience concludes with a showing of my Dad’s photographs that I found hidden away in a closet — the art show my Dad never had.

8FE57132-D3ED-423E-9497-F38764908E2B

0919386B-B1E9-490B-92FA-F25D9421B5E0

My Journey

As my Dad was dying he allowed me to ask him anything. Over the final year of his life, we sat down for a series of interviews. I knew early on that these interviews would be the foundation of the experience. From over twenty hours of recordings, I edited them down into nine powerful fragments that touched on the following:

- His upbringing and my upbringing

- His time spent as a volunteer firefighter and amateur fire-scene photographer

- The mysterious fires (our van erupted in flames and our family home burnt down) that devastated my family growing up

- His battle with cancer.

It can be challenging to find a balance between the tasks being asked of someone stepping into a participatory space —moving through the remains of a burned house — and the personal story that sits beneath the surface. This is especially true when the individual and collaborative actions of the participants are intended to unlock story fragments. In many ways, this mirrors the tension that I’ve personally felt making this piece. At the outset of the project it was very binary: I spent a lot of my energy fixated on my dad’s past and was obsessed with finding the answer to whether or not something had or had not taken place. But as I dug deeper I came to realize that it wasn’t so black and white, that in fact the shades of gray and the feelings of ambiguity and confusion were what made the experience most rich, vulnerable and human. These feelings are also true of what we’ve experienced with a loved one battling cancer — the quest to find answers and/or a cure often leaves you in an emotional fog.

When my Dad died my Mom stopped talking about him. They had been married for over 53 years. She knew about Where There’s Smoke, and as the Tribeca Film Festival approached I invited her numerous times to see the project, but she declined. Two days prior to its ending I received a call from my Mom asking if she could see the installation. She went through it with my son, my wife and me. It was one of the most powerful experiences I’ve ever had. As we sat in the gallery surrounded by my Dad’s photos she began to talk about him, telling numerous stories that we had never heard. Since that visit my Mom has continued to talk about him.

Where There’s Smoke held a space for us to grieve. While this was a wonderful experience for my family, I only came to realize the full power of it later. As it turns out, the clinically recommended time to grieve a spouse is nine months, at which point anti-depressives are prescribed.

Designing with Purpose

Although this was a personal project not connected to the Digital Storytelling Lab, we relied on methodologies developed at the lab. At Columbia DSL, when we start a project we’ll often shape a design question and design principles to help guide the development process.

The design question was: “How might we design a space that is safe and empowers patients, loved ones and caregivers to share stories of healing in an effort to improve care and empathy within a hospital environment?”

We based the project on four principles:

- The Trace — The participant can see their contributions within the experience.

- Granting Agency — The participant is granted agency to make decisions (as a team and individually) and they can identify how their actions impacted the experience.

- Thematic Frame — The participant can contribute to the experience because they have a pre-existing understanding of its foundation and from that a shared language emerges.

- Serendipity Management — Orchestrated micro-experiences where unexpected moments foster collaboration between participants. Design for blank space.

Over the years, I’ve come to realize the value of taking time to fully take stock of the “human experience” at the center of the immersive storytelling projects that I create. Long before any technology is ever discussed, we’ll playtest/prototype in an attempt to see

- What resonates and why?

- What moments grant agency and why?

- When are people collaborating and why?

- When are people working individually and why?

- What’s confusing and why?

- What’s engaging and why?

In an effort to prototype the core mechanics of the experience I grabbed some analog supplies (index cards, markers, paper, tape, Play-doh), built a Keynote presentation and created a playlist on Spotify to test some ideas that had been swirling around in my head. Since the experience explores memory and loss, I worked with a series of story fragments.

In immersive storytelling, onboarding and offboarding are some of the most critical moments you have. If you don’t effectively prime the participant, you lose them before it even starts. If you don’t catch the participant at the end, you risk destroying everything that’s come prior. I started to experiment with an onboarding exercise that would prime the participant:

“Imagine that you’re walking up to a place that you live now or that you’ve lived in the past. As you walk up to your front door place the key into the lock and open the door. . . ”

The visualization exercise took participants back to a place where they had lived and hopefully created a moment that helped provide a strong sense of home. After they had visualized moving through their home, recalling the smells, the way the light fell in certain rooms, what was on the walls and shelves, the exercise would end with them fast asleep in a comfortable bed dreaming. Slowly a sound would pull them from slumber and they would come to realize the room they were in was filling with thick black smoke and the sound was that of a smoke detector.

“Everyone you love and care about has made it out safely, but you have a few moments to save one thing that you are emotionally connected to. Something that holds deep meaning for you. There is only one rule — it can’t be digital. When you have the object in your hand please open your eyes. Can you now draw the object on the card in front of you? Once you finish please hand it to your partner who is sitting across from you.”

Understanding what someone is thinking, feeling and doing when they move through an immersive project is critical to its design. At the Columbia DSL we’ll often utilize a simple framework called “Think, Feel, Do” to get a sense of how the experience is flowing. We’ll map what we believe a participant will be thinking, feeling and doing within the beats of the experience as part of the participant journey documentation. Within the documentation, we’ll detail the participant’s steps throughout the experience beat by beat; this includes considering what the participant is doing prior to and after the experience. In addition, we’ll weave feedback loops into the prototype itself so that participants can share what they were actually thinking, feeling and doing during the testing.

My heart skipped a beat as I listened to feedback from participants. Within the comments, I saw a mirror to my experience in little pieces. The use of simple prototyping materials and my willingness to be vulnerable in the moment was unlocking something for me. It was reflecting back emotions that my family and I had experienced over the last few years. I’m not saying that it had the same emotional intensity (nor should it have), but the fact that similar emotions were present at all was amazing to me. And when someone walked up at the close of the evening and shared a powerful story with me about the loss of their own parent, I realized that sharing my own family’s story had created a space for others to share too. In a room full of strangers, the fact that one person felt a level of trust to share something so personal with me was incredibly humbling.

Where There’s Smoke is currently being developed as a browser-based experience that includes a tool kit for building immersive learning and healing spaces. We’re also working on an art book that will feature a collection of my Dad’s fire slides pulled from thousands of photos shot between 1968 and 1988. And in addition to the immersive documentary side of the project, we’re developing a fictional film/TV series and a YA novel based on these true events.

Note: This is the first year the Columbia Digital Storytelling Lab has recognized work created by any of its members. Where There’s Smoke was deemed eligible because it was a personal project and not produced by the DSL. Like other members of the Digital Dozen, it was included based on voting by the Columbia community. Lab members whose work is considered for the Digital Dozen are asked to recuse themselves from the voting process.

Lance Weiler is a storyteller, entrepreneur and thought leader. An alumnus of the Sundance Screenwriting Lab, he is recognized as a pioneer in mixing storytelling and technology. Wired magazine named him “One of twenty-five people helping to re-invent entertainment” when he disrupted the industry with the release of his first feature, The Last Broadcast. Weiler co-wrote, co-directed and co-produced, and ultimately self-distributed The Last Broadcast, which was made for $900 and went on to gross over $5 million as the first all-digital release of a motion picture to theaters via satellite. The distribution methods that Weiler introduced have since become the standard for digital cinema distribution today. After the success of The Last Broadcast, he began to work extensively as a writer, director and producer, developing TV and film properties for FOX, TNT, Starz and Endomel.

Lance Weiler is a storyteller, entrepreneur and thought leader. An alumnus of the Sundance Screenwriting Lab, he is recognized as a pioneer in mixing storytelling and technology. Wired magazine named him “One of twenty-five people helping to re-invent entertainment” when he disrupted the industry with the release of his first feature, The Last Broadcast. Weiler co-wrote, co-directed and co-produced, and ultimately self-distributed The Last Broadcast, which was made for $900 and went on to gross over $5 million as the first all-digital release of a motion picture to theaters via satellite. The distribution methods that Weiler introduced have since become the standard for digital cinema distribution today. After the success of The Last Broadcast, he began to work extensively as a writer, director and producer, developing TV and film properties for FOX, TNT, Starz and Endomel.

Weiler approaches his work from a systems thinking perspective. He often develops new methods and technologies to tell stories and reach audiences in innovative ways. For instance, he created a cinema ARG (augmented reality game) around his second feature, Head Trauma. Over 2.5 million people experienced the game via theaters, mobile drive-ins, phones and online. In recognition of these cinematic innovations, Businessweek named Lance “One of the 18 Who Changed Hollywood.” Others on the list included Thomas Edison, George Lucas and Steve Jobs.

In addition to his own projects, Lance often collaborates with others. In 2010, he was nominated for an International Emmy in digital fiction for his work on “Collapsus: The Energy Risk Conspiracy.” In 2014, he was Creative Director and Experience Designer of “Body/Mind/Change,” an immersive storytelling project in collaboration with David Cronenberg, the Toronto International Film Festival, and the Canadian Film Centre. “Body/Mind/Change” was recognized for its innovative use of story and code, winning the MUSE Jim Blackaby Ingenuity Award from the American Alliance of Museums and receiving a Webby Honorable Mention in the Games and Augmented Reality category.

Since 2013, Lance has been a Founding Member and Director of the Columbia University School of the Arts’ Digital Storytelling Lab (DSL), leading the lab’s activities and helping to shape its enduring vision. The DSL’s mission, to explore new forms and functions of storytelling while encouraging cross-disciplinary collaboration, focuses specifically on the ways in which story can be harnessed as a tool to innovate, educate, mobilize, communicate, and entertain.

Weiler’s creative uses of emergent technology have made him highly sought-after in the entertainment industry, where he helps companies reshape their media holdings for the 21st century. He has consulted for IBM, Twitter, Microsoft, Samsung, Chernin Entertainment, Ubisoft, Penguin Books, the U.S. State Department, CAA, Ogilvy, McCann-Erickson and others, helping to create, design and shape entertainment properties that reach billions of people. With his unique understanding of interdisciplinary teams and how to grow businesses in an ever-shifting digital landscape, he was invited after speaking at the World Economic Forum in 2012 to serve on two of its steering committees, one on the future of content creation and the other on digital governance. He has also given talks at UN events, at MIT, USC and NYU, at Sundance, Cannes and South by Southwest, at the Tribeca, Toronto, Berlin and Los Angeles Film Festivals, at Games for Change, at the Future of Storytelling Summit and at TED. And he has written on the future of storytelling for such publications as Quartz, Filmmaker and IndieWire.

“At a precarious moment for everyone in the film and television business, where questions surround the future of entertainment (and narrative itself), Weiler’s work has become more relevant than ever. . . . ‘Where There’s Smoke’ is the latest example of his ability to go beyond the static boundaries of most so-called ‘next level’ media like virtual reality. He has described the project as ‘an emphatic healing/learning experience,’ but it’s essentially a first-person documentary under the guise of an escape room, pushing the technology and the documentary tradition in a fresh direction.”