Ancestors

Take a selfie and become the great-great-grandparent of a human 200 years in the future.

Although people can imagine the future, it is very hard for us to look further than roughly 30 years. Yet having a longer, intergenerational horizon is very urgent in light of the current climate crises.

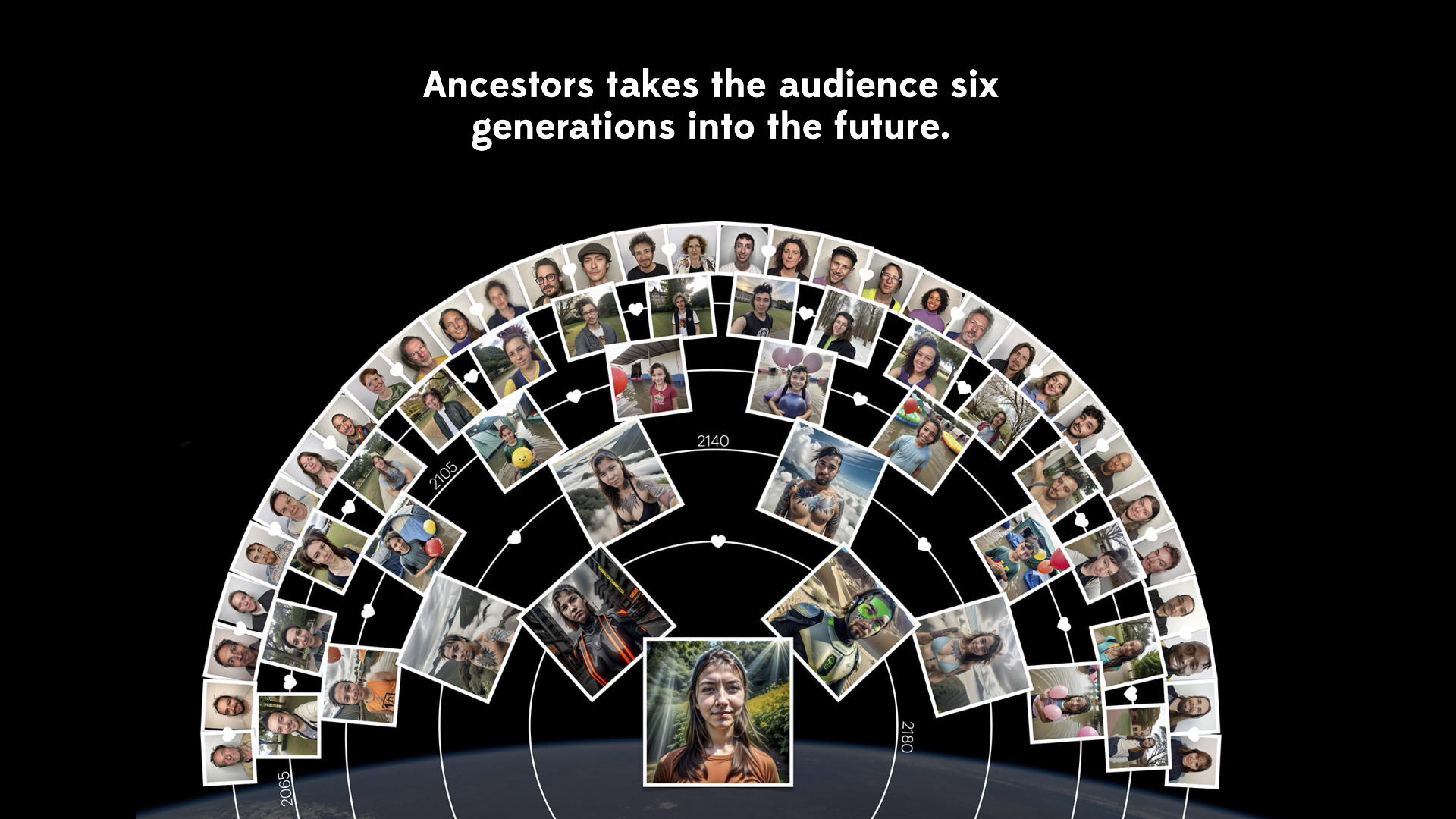

Ancestors takes the audience six generations into the future. It is an interactive and immersive group experience that uses AI to create connections between you and others in the room — a thought-provoking adventure that brings people together in an entirely new way. Through fun interactions, original storytelling, deep conversations and unexpected encounters, it aims to create a deep sense of empathy with future generations. What kind of world will we leave for them?

Ancestors takes the audience six generations into the future. It is an interactive and immersive group experience that uses AI to create connections between you and others in the room — a thought-provoking adventure that brings people together in an entirely new way. Through fun interactions, original storytelling, deep conversations and unexpected encounters, it aims to create a deep sense of empathy with future generations. What kind of world will we leave for them?

Guided by your own smartphones, you and your fellow participants will explore together the challenges of tomorrow, discovering in the process how collaboration is key to shaping a better world. You tell the stories of those who will come after us, stepping into a future shaped by the actions of today. Your smartphone becomes your guide, leading you through a world where the impact of climate change, technological advancements and social challenges is deeply felt. With the help of AI, your decisions and interactions shape the narrative and influence the collective outcome of the experience.

This isn’t a passive performance; it’s a participatory journey in which the audience is very much part of the story. As you explore these possible futures, you’ll find yourself questioning your relationship with technology, society and the planet. It’s a unique combination of speculative fiction, interactive storytelling and real-time decision-making that will stay with you long after the experience ends. Will humanity find solutions to these challenges? And what role will you play?

HOW DOES IT WORK?

First, you take a selfie.

Then, using AI, we create the face of a virtual child from your selfie and that of another (random) audience member., making both of you virtual parents.

Next, find two other people with the same picture on their phone. The four of you have become grandparents. What do the four of you think your grandchild’s life will look like?

With every generation you are asked to imagine these future lives together.

The Smartphone Orchestra synchronizes anywhere from ten to thousands of smartphones to form, potentially, the biggest orchestra in the world — an orchestra in which every participant’s smartphone plays a unique part. The technology opens up numerous possibilities to tell stories or share experiences with mass audiences. It serves as a tool to create group experiences — to tell stories with the audience instead of to them. The concept for the Smartphone Orchestra’s productions was developed by creative director Steye Hallema, lead developer Hidde de Jong and musician and composer Eric Magnée.

Steye Hallema is a seasoned digital storyteller and director. The son of a magician, he studied music and visual arts at the Royal School of Music, Dance and Art in The Hague and became creative leader of the Dutch broadcaster VPRO’s Medialab. His virtual reality music video What do we care4 was nominated for an UK music award in 2015 and was a worldwide hit among virtual reality early adopters. This project landed him a job as creative director for Jaunt VR, a Disney-backed VR startup in Silicon Valley. The cinematic VR experience Ashes to Ashes, which Steye co-directed, won gold at the Dutch VR Awards and was nominated for the Dutch Oscars. Weltatem, a virtual reality opera game which Steye directed, won two Dutch Game Awards.

Steye Hallema is a seasoned digital storyteller and director. The son of a magician, he studied music and visual arts at the Royal School of Music, Dance and Art in The Hague and became creative leader of the Dutch broadcaster VPRO’s Medialab. His virtual reality music video What do we care4 was nominated for an UK music award in 2015 and was a worldwide hit among virtual reality early adopters. This project landed him a job as creative director for Jaunt VR, a Disney-backed VR startup in Silicon Valley. The cinematic VR experience Ashes to Ashes, which Steye co-directed, won gold at the Dutch VR Awards and was nominated for the Dutch Oscars. Weltatem, a virtual reality opera game which Steye directed, won two Dutch Game Awards.

INTERVIEW WITH STEYE HALLEMA

Columbia DSL: How did you get started with this?

Steye Hallema: I kind of started my career as a musician. I was part of a multimedia collective called Pip’s Lab — this is at the beginning of the 2000s. As a musician, I was always looking for ways to get attention for my music. Getting attention for music is really hard, and at a certain point, I kind of realized that the digital stuff I would make up to promote my music was actually easier to sell than the music itself. So I slowly, gradually morphed into becoming a multimedia director. And now I’m already doing this for like 20 years or more.”

DSL: How did the Smartphone Orchestra develop?

SH: Smartphone Orchestra is kind of a medium we’ve been developing over the last 10 years in which we use the smartphones of the audience to create group experiences. It started as a musical idea. Again, it was a ruse to sell my music. The first thing I built was a mockup system. I had a grid of 25 speakers in my living room, sending each output to the shittiest speaker I could find. We were trying to figure out how music would sound when distributed across multiple devices. And at a certain point we realized we were organizing the arena where a Smartphone Orchestra piece happens — because audiences are so conditioned to sit and look at a stage, and all of a sudden,it’s happening within them.

DSL: Tell us about some of your key projects — Music for Smartphones, The Social Sorting Experiment, Emojiii.

SH: We’re still playing our first piece, Music for Smartphones, that we made 10 years ago. And it’s still—everyone’s like, ‘Wow, this is amazing.’ The Social Sorting Experiment was about the Cambridge Analytica scandal. We made people judge each other: ‘Who has more beautiful ears? Who will live longer? Who would I rather donate my kidney to?’ It was a very provocative but strong illustration of the power that social media companies acquire over us.

Emoji is the language spoken by the most people in the world, but it’s made by big tech companies. So we made a game where people mimic emoji faces—hundreds of people making funny faces to each other. It’s hilarious and light, but it raises the question: What does it mean to speak a language designed by corporations?

Ancestors is our most elaborate, most advanced piece so far. It deals with themes of family, belonging, and climate change. We built it over multiple tests, refining it until we had something that truly resonated with audiences.

“Art and technology have always been linked. Look at Rembrandt — he had a lab where they worked on advanced techniques to create his paintings.”

DSL: What’s your development process like?

SH: When we create a piece, we write a script based on our assumptions, then let people interact with it. And then you realize what’s actually happening, so you throw away 80 per cent of your assumptions and replace them with audience feedback.

For Ancestors, we had numerous small tests — sometimes just us at a table. Then bigger tests with real audiences. Even the premiere wasn’t the ‘final version’—the real thing came after refining based on audience response. We also adapt pieces for different audiences, like making a youth version of Ancestors for a children’s media festival.

DSL: What’s the role of the facilitator in your pieces?

SH: The facilitator is crucial. A Smartphone Orchestra piece requires dedication from the audience. If people are networking and drinking, they won’t engage. So we create a ‘protected arena’ where the experience can thrive. And we use ‘seduction through silliness.’ If you start with humor and playfulness, people relax. And once they’re engaged, you can lead them into something deeper.

DSL: Do you find the reaction to your work changes in different cultural contexts?

SH: Our work really thrives in America because it’s an extroverted culture — people are easy chatters. But when we performed in a quieter region of the Netherlands, people were more hesitant. It worked, but it was different. In some Asian countries, audiences are less expressive in the moment, but afterward they come up and say, ‘This was really beautiful. Thank you.’

DSL: Where do you want to take it from here?

SH: Now that we’ve mastered the medium, I want to make the Smartphone Orchestra a platform where other creators can tell stories. We want to operate like a label—other artists could create Smartphone Orchestra pieces, and they would receive royalties. It could become its own creative ecosystem.

But sustaining the project is challenging. We had momentum, then Covid hit, and suddenly it wasn’t cool to gather in groups with smartphones anymore. That was a painful period.

DSL: How do you feel about the state of interactive storytelling in general?

SH: I think we are part of a new school [of art]. Digital storytelling festivals like Tribeca, South by Southwest, IDFA — these places form a scene that feels like an artistic movement. But art and technology have always been linked. Look at Rembrandt — he had a lab where his team worked on advanced techniques to create his paintings.

We are doing the same thing with digital storytelling. The challenge is that we’re getting really good at interactive storytelling, but the hype is over. VR is finally reaching maturity, but funding is harder to find.

DSL: What advice do you have for new artists and creators?

SH: Start with simple prototypes. Before diving into complex technology, test ideas with paper prototyping.

The medium and the message need to be one. Too often, people try to tell a story and then bend a new medium to fit it. Instead, let the medium shape the story.

Media is becoming deeply personal. Netflix, Instagram — everything is tailored to the individual. Artists should reflect on this and create works that engage the player directly.

Study behavioral psychology. Understanding your audience — your ‘player’ — will help you craft better experiences.

My biggest advice: Be the boldest opportunist you can be. Be bold in seeking funding and support. And take care of your team. If you’re doing pioneering work, it’s hard. Value each other.