Cat Royale

Three cats lived inside an environment created by the artists. Ghostbuster, Pumpkin and Clover spent time inside each day for 12 days. Their every need was catered to. They had food, drink and air conditioning. They had high ledges to watch from, cubbyholes to snooze in and a floor to ceiling scratch post. Every surface was covered in carpet so they could climb and explore freely.

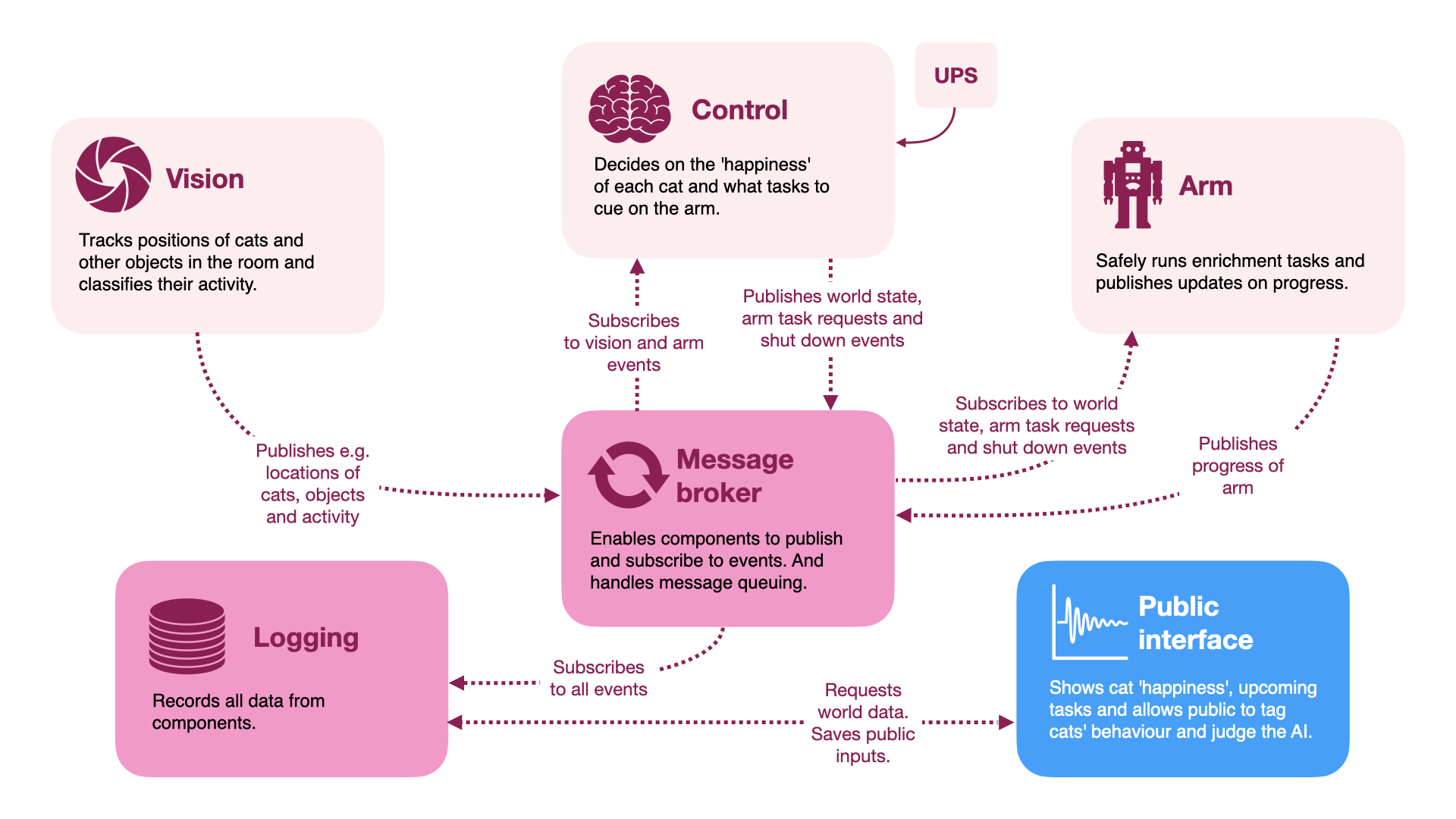

At the center of the room was a robot arm controlled by an AI which was connected to a computer vision system. Every few minutes the AI instructed the robot to offer a game to the cats. The robot threw balls or dropped them into a ball run. It dangled feathers, offered snacks and introduced a cardboard box. It rang bells and dragged a toy mouse. Over time it learned which games each cat liked best.

To ensure the comfort and safety of the cats, experts in animal welfare were involved in the design of the project from the start. Senior staff from the RSPCA were supervising throughout the 12 days.

Co-commissioned by Science Gallery London and Queensland Museum for the World Science Festival Brisbane, Cat Royale was developed in collaboration with the Mixed Reality Lab at the University of Nottingham. The work was first presented in March and April 2023 as a time-delayed video stream at the World Science Fair in Brisbane to an audience of more than 400,000 people. Daily highlight films were shown on YouTube and Facebook. In May 2024 the project moved into a new phase with its presentation at CHI ’24: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Honolulu and the publication of “Designing Multispecies Worlds for Robots, Cats, and Humans” in the Association for Computing Machinery’s CHI ’24: Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Blast Theory makes interactive art to explore social and political questions. The group’s work places the public at the center of unusual and sometimes unsettling experiences that explore interactivity and the social and political aspects of technology. They draw on popular culture and new technologies to make performances, games, films, apps and installations, creating new forms of performance and interactive art that play out on the internet and in digital broadcasts and live performance. Founded in 1991 and based in Brighton, England, they are led by Matt Adams and Nick Tandavanitj.

Matt Adams co-founded Blast Theory in 1991 with Ju Row Farr, who remained with the group until 2023. He was Visiting Professor in Interactive Media at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama from 2007 to 2014 and served on the South East Area Council of Arts Council England from 2012 to 2019. He is an Honorary Fellow at the University of Exeter.

Nick Tandavanitj has worked with Blast Theory since 1994. In this time, Nick has focused on creative approaches to computing and develooping particular skills in 3D modelling, technical design and programming for interactive installations and web based artwork. He studied Art & Social Context at Dartington College of Arts from 1990-1993. Following college, he became friendly with the artists at Jamaica Street Studios in Bristol. In 2003, he became an Arts and Humanities Research Council Research Fellow at the University of Nottingham, undertaking a nine-month program of research into artistic, social and gaming applications which use mobile technology.

The artists work closely with researchers and scientists and have collaborated with the Mixed Reality Lab at the University of Nottingham since 1997. They teach and lecture internationally, including at the Sorbonne, Stanford University and the Royal College of Art, and they curated the Screen series for Live Culture at Tate Modern in London. They have been nominated for four BAFTAs and won the Golden Nica at Prix Ars Electronica and the Nam June Paik Art Center Award. They have two permanent installations in museums: Exploratron (2004) at London’s Science Museum and Hurricane (2013) at the Red Cross Museum in Geneva.

Early works such as Gunmen Kill Three (1991), Chemical Wedding (1994) and Stampede (1994) drew on club culture to create multimedia performances, often accompanied by bands and DJs, that invited participation. In 1997, a nine-month residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin produced Safehouse (1997) and Kidnap (1998), in which two members of the public were kidnapped as part of a lottery and the result was streamed online. Desert Rain (1999), a large-scale installation, performance and game using virtual reality, was their first collaboration with the Mixed Reality Lab at the University of Nottingham.

An Explicit Volume (2001), an interactive installation using page-turners to control nine pornographic books, was one of a sequence of works that use found imagery and/or sexual material. Can You See Me Now? (2001) placed online players alongside Blast Theory runners in a chase game played online and on the streets. It was succeeded by Uncle Roy All Around You (2003), in which players searched through the streets for Uncle Roy using handheld computers and a virtual city.

In the context of the global financial crisis of 2008, Blast Theory made a series of explicitly political works, starting with Ulrike and Eamon Compliant (2009) at the Venice Biennale. They have repeatedly engaged with the history of Northern Ireland, notably in Fixing Point (2011) which documents the case of Seamus Ruddy, a man who has been missing since 1985. With Karen (2015) — which was cited in the first year of Columbia DSL’s awards program — they put a life coach on a smartphone as a way of investigating how data is harvested and users are manipulated.

The group has systematically explored the role of the audience. Their game projects have probed the fundamental laws of games and of play, posing questions about the boundaries between games and the real world and contributing extensively to debates about the development of games as an art form. Cumulatively, their projects tackle important questions about the meaning and limitations of interaction. Who is invited to speak? Under what conditions? And what can be said that is truly meaningful?

Q&A WITH BLAST THEORY

This interview was conducted over video by Columbia DSL founding director Lance Weiler. It has been edited for clarity and length.Lance Weiler: I have to say, I’m totally obsessed with this project. So many things about it are amazing. What were you hoping to explore by bringing artificial intelligence and animal welfare together in this kind of utopian setting?

Nick Tandavanitj: We’d been working with generative AI — early versions of ChatGPT — and exploring its broader implications for society. As part of our process, we often ask each other questions and conduct internal interviews to formalize discussions.

When we discussed AI, what intrigued us most was its move into care and well-being — areas traditionally human-led. That led us to a pivotal question: Would you let a robot wash you? We discussed that in personal terms — imagining ourselves older or infirm — and it led to deeper reflections on intimacy and expressions of care.

Lance: And then came cats?

Nick: Matt Adams suggested it had to be cats. They’re imperious, self-determined, and not as companionable as dogs. Their independence was interesting to us. Plus, most of the team has cats, and we’re familiar with their mysterious nature. They’re like AI in that way — both are black boxes we can’t fully understand.

Lance: Once you had that, how did you go about designing the experience and working with the cats?

Nick: We quickly learned the challenges — working with animals and university ethics boards, for example. But we had the opportunity to be cultural ambassadors for the UK’s Trustworthy Autonomous Systems Hub, which gave us access to roboticists, machine learning researchers, and a network of labs.

We had a fairly complete idea early on: What if an AI were in charge of the happiness of cats? From there, it was a matter of practicalities. Would we take robot arms into homes? Create a gallery installation? How would it work technically?

We brought in researchers from several UK universities and simultaneously considered the tech, cat experience, and public engagement. Our goal was to create something genuinely rewarding and enriching for the cats — not to experiment on them. The cats became stand-ins for humans as we explored the dynamics of robotic caregiving.

Lance: Walk me through the build process.

Nick: It took around 18 months. We trained a computer vision system using thousands of video clips and invited the public to help tag these via the Zooniverse platform. That gave us a functional system from day one that could evolve and adapt.

We also made sure to tell the story from the beginning. It wasn’t just about promoting the work at the end — audiences were part of the process. They saw the first moments the cats interacted with the robot arm. That openness helped people understand the complexity of what we were doing.

The project evolved from a four-page sketch to a detailed technical specification. It went through three university ethics boards, saw team changes, and included consultations with animal behaviorists and the RSPCA. We had to adjust plans constantly.

Eventually, we found someone named Ed who owned nine cats that were used to traveling and engaging with unusual environments. His cats became central to the project. We designed a space specifically for them — with curves, cubby holes, climbing areas — all informed by behaviorist consultations.

Lance: It’s fascinating how the cats served as both collaborators and proxies for human experiences.

Nick: Yes. And collaborating with someone like Professor Steve Benford at Nottingham’s Mixed Reality Lab was transformative. He took our core concept — using a robot arm to care for cats — and framed it as a novel research question.

There’s a growing movement in computer science pushing beyond human-centered design toward multispecies approaches. The idea is that it’s not just humans adapting technology — animals are, too. That was a powerful insight for us.

Lance: Let’s talk about the AI itself. How did it make decisions about cat welfare? Were there any surprises?

Nick: The AI was driven by a multi-armed bandit algorithm — the same kind used by platforms like Amazon to make recommendations. It chose from more than 50 games based on cat engagement over 500 sessions.

The AI’s decisions were fairly predictable. The cats, however, were not. One cat, Clover, destroyed a toy the AI thought was her favorite. It hadn’t factored in how long she wanted to play. When it tried to move on, she pulled the toy off the arm and ran away with it.

We also found that the computer vision task was harder than expected. Despite training on over 8,000 video clips, the system struggled to distinguish between behaviors like sleeping, pouncing, or grooming. We ultimately grouped them into broader categories, but it was a challenge.

While we were building the project, newer tools started to emerge — like spatial language models — that made our existing technology feel outdated. But we had to stick with what we’d built.

Lance: How did you think about audience experience and emotional resonance?

Nick: We don’t aim to dictate how people should feel. We want audiences to draw their own conclusions. That made communication complex — we had to speak to art audiences, local community members, and tech-savvy viewers.

We worked with an audience advisory panel to help shape our messaging. The project premiered as a livestream at the World Science Festival in Australia, with daily highlight videos on YouTube and social media. These sparked intense conversations — from ethics to cat care debates.

Reactions varied widely. Some people were upset. Others asked where they could buy a version for their own cat. It was rewarding to see such a spectrum of engagement.

We wanted people to feel immersed, to experience the cats’ world. That’s why the livestream ran six hours a day. It wasn’t about forcing meaning — it was about being present with the cats.

Lance: Final question. What advice would you give other artists working with emerging tech and live subjects — particularly around ethics and collaboration?

Nick: First, have a deep duty of care — for your subjects, for your collaborators, and for the ecosystems you’re designing within. That’s non-negotiable.

Second, assemble a multidisciplinary team early. Having artists, researchers, developers, and advisors in the room makes all the difference. It enables smarter, more thoughtful decisions.

Plan for the ethics approval process. It can be long and unpredictable, especially when multiple institutions are involved. Give yourself that buffer.

And be ready for complexity. We had doors that had to remain closed so cats wouldn’t escape, robot systems running on unfamiliar platforms, and communication challenges across disciplines. It was a rare and powerful convergence of art, research, and tech.