Ceci est mon cœur

“Our aim is to show that if we accept our traumas, we are capable of reclaiming our bodies and thus reconciling with them, and with ourselves.”

—Les Frères Blies

Ceci est mon coeur — “this is my heart” in English — emphasizes self-acceptance and showcases the beauty of human fragility. It is an extraordinary love story, the tale of a child’s reconciliation with his body. A sensory and narrative creation that highlights the distorted representation we have of our own bodies.

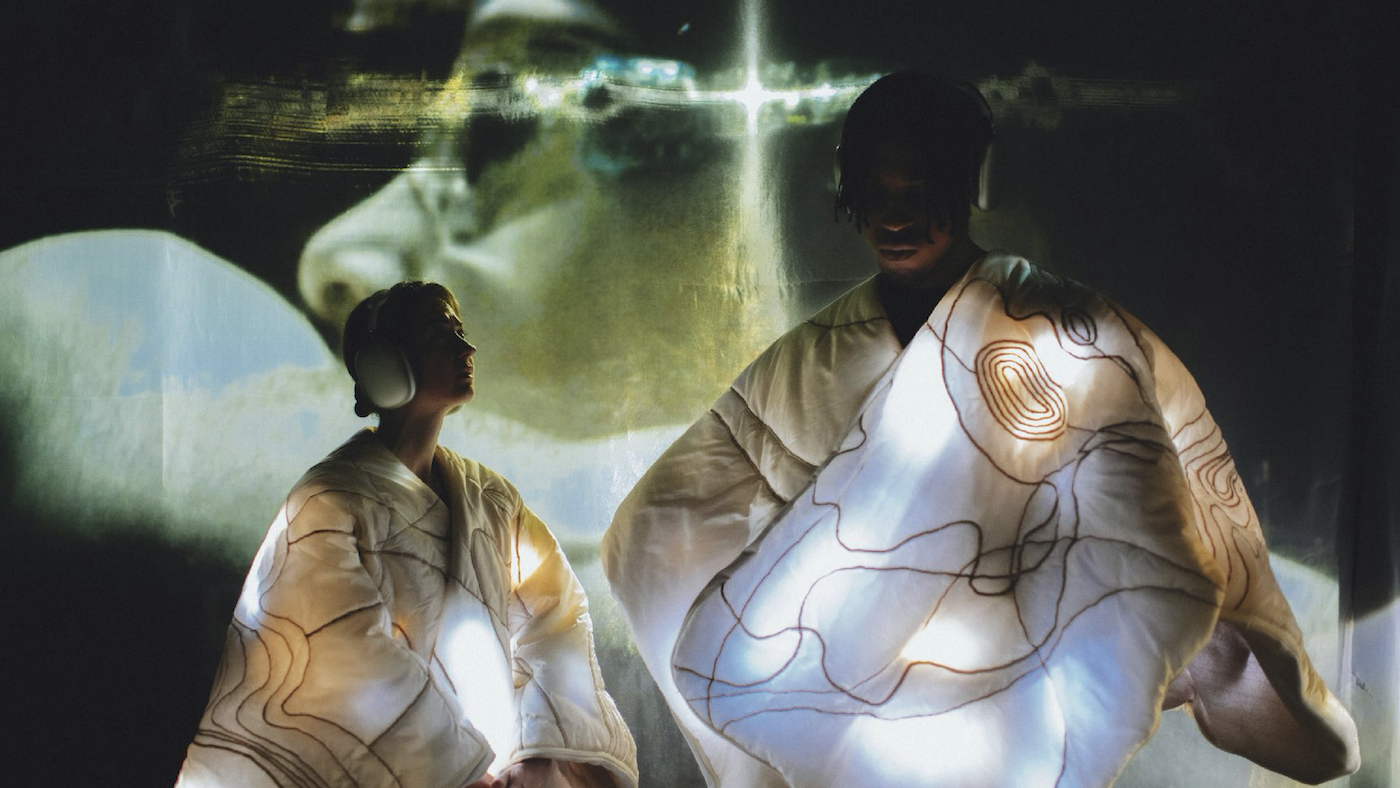

Conceived as a collective site-specific work, Ceci est mon coeur is an installation designed for cultural and artistic centers and spaces. It is an immersive tale in which members of the public, wrapped in a connected garment embellished with luminous embroidery, are carried away in a poetic experience, both oral and visual. Ceci est mon coeur offers a sensory odyssey in which the audience sees the connected garment light up in sync with the text of the story. A ballet of lights takes shape under the impulse of the story, a story conceived as a dialogue between the narrator and his own body. It is an intimate work that integrates visual projections, a soundscape and the choreography of light that moves through people’s bodies. Everything seems to breathe and react to the story. At the end of the 35-minute experience is an off-boarding process in which visitors encounter a series of 12 photographic portraits of young adults who, through the photographer’s lens, dramatize the story they construct with their bodies.

Reclaiming one’s body is a burningly modern subject. One in five girls and one in ten boys report having been sexually abused before the age of 18. Around 20% of students aged 12 to 18 have been victims of bullying. Children with disabilities or special health needs are more likely to be victims of bullying. By the age of 13, around 53 per cent of girls are unhappy with their bodies. By the age of 17, this figure has risen to 78 per cent. New research shows that one in four boys also suffers from body dysmorphia, a malaise that can lead to serious problems such as academic failure or depression. Trauma is omnipresent in our society, whether we’re a child or an adult. And our bodies remember.

Ceci est mon coeur addresses these issues from a perspective of reconciliation and immersive poetry. By staging our own intimacy and fragility, it aims to show that if we accept our traumas, we are capable of reclaiming our bodies and thus reconciling with them, and with ourselves.

The experience is unique: For the first time, the public is invited to take part in a collective experience centered around a connected garment — a garment of light immersing the audience in a singular visual universe.

Several silk fabric veils divide a room of approximately 100 square meters, allowing spectators to move around the space. Four video projectors are installed around the room, projecting onto it a visual universe of generative art and live-action video. Wearing a connected garment made up of addressable LEDs, spectators wander around the room. The veils are translucent, allowing the projections to pass through. Viewers can observe the work from different perspectives.

Visitors wear noise-canceling, high-definition headphones. They listen to the narrator’s voice as he tells the story of his reconciliation with his body. The garment is choreographed to the rhythm of the text and the music. What counts is not the interaction between participants but the idea of experiencing a shared moment together. The concept of Ceci est mon coeur is based on this desire to let the body speak for itself in order to highlight a magnificent and necessary reconciliation — a reconciliation that involves looking at and listening to others, for it is through them that we heal. The emphasis is not on how the other looks at you, but rather on the idea of feeling the other’s presence around you.

Stéphane Hueber-Blies and Nicolas Blies — «les frères Blies» — are filmmakers and digital artists who create their work together. Natives of Strasbourg in the historical region of Alsace in France, they have lived and worked in Luxembourg since 2013.

In 2015, they conceptualized the transmedia music documentary Soundhunters in co-production with ARTE, the European culture channel. Soundhunters was imagined to transform the world into an infinite musical instrument. It was released in 2015 in collaboration with a number of international artists, including Jean-Michel Jarre, Simonne Jones and Blixa Bargeld. In 2016, the project was placed under the patronage of UNESCO and the Blies brothers were invited to present it at Lincoln Center during the New York Film Festival.

In 2019, they wrote and directed their first feature-length documentary, Zero Impunity, about the impunity of sexual violence in war zones. Combining animation and live action, the film is considered one of the precursors in this field. The Blies brothers were invited by the Annecy International Animation Film Festival to take part in the festival’s traditional masterclass, where they discussed the issue of sexual violence in animation. In 2021, the film was nominated for the Trophées Francophones du Cinéma in the “Best Documentary” category. Continuing their work on the hybridization of forms, the Blies brothers went on to develop the digital art installation Ceci est mon coeur while also writing their first animated feature, Les deux frères.

Ceci est mon coeur was produced by Marion Guth and François Le Gall of a_BAHN, a Luxembourg-based production company, cofounded by Guth and the Blies brothers in 2013, that has been developing the art of hybridization: breaking free from established norms by working at the intersection of forms and genres. Written by Stéphane Hueber-Blies; music by Nicolas Blies.

Q&A WITH THE ARTISTS

This interview was conducted via videoconference in April 2025 by Frank Rose of Columbia DSL. It has been edited for length and clarity.Frank Rose: I want to start with the idea for this project. What led you to it?

Nicolas Blies: It started three years ago. Stéphane and I were both struggling to connect with people, and after a lot of conversations, we realized we each had a complicated relationship with our bodies. It was hard to love ourselves, and if you can’t love yourself, it’s impossible to truly love others. That was the starting point.

We discovered that although we had very different experiences, we shared a similar journey. For Stéphane, the root was sexual abuse when he was young. For me, it was a combination of illnesses that made me feel alienated from my body. Despite the different sources, we both went through the same phases: denial, self-destruction, invisibility, and eventually, the long road toward reconciliation.

Frank: So trauma was the common thread?

Nicolas: The project started from our traumas, yes. But the story we wanted to tell was about reconciliation with the body. Trauma doesn’t have to be dramatic to be impactful. Bullying, body changes, gender dysphoria, or even how others perceive you can leave lasting marks. These experiences live on in us, and that dissonance between how you see yourself and how others see you is where a lot of pain begins.

Frank: Would you be comfortable talking about your own experience?

Nicolas: When I was young—and still today—it was difficult for me to look at myself in a mirror. I avoided reflections. I hated what I saw. I had a condition with my back that required wearing a brace for two years. In secondary school, I had to hide it, but I failed. Kids would knock on my back to expose me, call me a monster. It was humiliating.

Stéphane Hueber-Blies: On my side it was a little bit different. I was sexually abused when I was nine, and from that moment I said to myself that my body betrayed me. It betrayed me. I was very angry with it, so I tried to destroy it. And it’s only two or three years ago that I reconciled with it.

Frank: When you say you felt that your body betrayed you, do you mean that you blamed your body for the abuse, for getting you in that situation?

Stéphane: Yeah. Yeah. Because it didn’t protect me. I was nine. It didn’t say no because I was sexually abused by a woman. And all this time I said to myself it wasn’t sexual abuse, because it was a woman and I was a little boy. It was difficult for me to accept that I was sexually abused. It betrayed me because — I don’t know if I can say it, but I was nine, a little erection — so you feel guilty. You think it’s your fault. But I was nine. This woman was 35.

It’s not normal. It’s not normal at all. So I tried to destroy myself in different ways. I jumped from a plane without taking care of my parachute, so I almost died that day. When I was 18 I ran very fast with my car straight in a wall. I smoked. I drank. Because I just wanted to hurt my body.

Frank: When you were growing up and experiencing these traumas, how much did you share with each other?

Nicolas: Nothing. Silence was the rule. We didn’t talk about intimacy with each other or with our parents. That’s why we need to talk now. Fragility is powerful. Especially for men, showing vulnerability is courageous. Empathy and fragility can save the world.

“I had been abused. Nicolas had illnesses. Different traumas, but a shared journey. We decided to blend our stories into one narrative without saying which part belonged to whom. That allowed us to create something universal.”

Frank: How did you start to transmute these traumas into this project?

Nicolas: After we realized we needed to do something with these experiences, we took on a personal challenge. We enrolled in a theater workshop in Paris, not to become actors, but to explore intimacy in public. The teacher helped us confront our physical presence.

One exercise involved lying on the floor and letting micro-pulsations—tiny involuntary movements—flow through the body. For me, it became intense. My body started to twist and move on its own. My elbow reached toward my neck, my knees toward my back. It felt like a disarticulation. For 45 minutes I just lay there, crying. But it was also the first time my body spoke to me. I realized we were one. That I didn’t need to hate it anymore. We were partners.

Frank: That sounds transformative.

Nicolas: It was. And that’s what we wanted to capture in the project. We framed it as a love story—a rupture and a reconciliation between you and your body. You separate, experience pain, and finally come back together and forgive.

Frank: How did you approach turning this into a narrative?

Stéphane: We had an epiphany. I had been abused. Nicolas had illnesses. Different traumas, but a shared journey. We decided to blend our stories into one narrative without saying which part belonged to whom. That allowed us to create something universal. We weren’t aiming to make a therapeutic piece, but we hoped others could see themselves in it.

Frank: How did you keep it from becoming too personal or self-indulgent?

Nicolas: That was the hardest part. We poured our intimacy into the raw materials—our family archives, our children’s voices, their songs. But we were always mindful that the audience should take ownership of the story. The body is the intersection of the self and society, so we played on that duality. It’s personal, but it’s also communal.

Frank: How did you go from writing to producing the full piece?

Stéphane: We knew from the beginning that this wouldn’t be a traditional story. We wanted video mapping, a connected garment, immersive sound. But first came the story. We outlined the structure, then I wrote the text, using repetition and rhythm to create something musical and spoken-word-like. Then Nicolas took the text and composed the music around it. Sound came first, always.

Frank: What effect did you want the music to have?

Nicolas: I started with classical guitar—my childhood instrument. It brought a sense of purity and melancholy. But later, I added harsh electronic sounds, very aggressive, almost industrial. I was angry. That contrast became crucial. The project is about movement, so the music needed to reflect that—sometimes accompanying the text, sometimes opposing it. It was a constant balancing act.

Frank: And the garment—how did that come together?

Nicolas: That took time. We had a vision of a minimalist, Japanese-style blanket that anyone could wear. It had to be handmade—silk, cotton, layered with care. We worked with a fashion designer and a lead developer to create the first prototypes in our Luxembourg studio. It took a month to build each one.

The garment had to dance with the music, with the visuals, with the text. Everything had to be choreographed. We were afraid of overwhelming the audience with too many layers—sound, visuals, words. So we treated it like cooking, carefully balancing each ingredient. People told us afterward that the experience felt like only ten or 15 minutes, even though it was 35. That was our goal.

Frank: What are you working on now?

Nicolas: We want to keep exploring this fusion of poetry and music. Our next immersive piece builds on that, using spoken word and sound as the core. It’s exciting because we’re returning to our roots—Stéphane with literature, me with music. We’re also developing two feature films, still grounded in our personal stories and family history. We’re focused now on intimacy, and making it universal.

Frank: Thank you so much. This has been a remarkable conversation.

Nicolas: Thank you. These were questions we’ve never been asked before. It means a lot to be recognized this way.

IN THE MEDIA

“A mesmerizing blend of physical installation (featuring a connected garment enhanced with luminous embroidery that aligns with the unfolding narrative) and visual projection, all of which is set to an enveloping soundtrack. Over the course of 35 minutes, the sensory experience probes our distorted relationship to our bodies through the tale of a child reconciling with his own.”—Cool Hunting