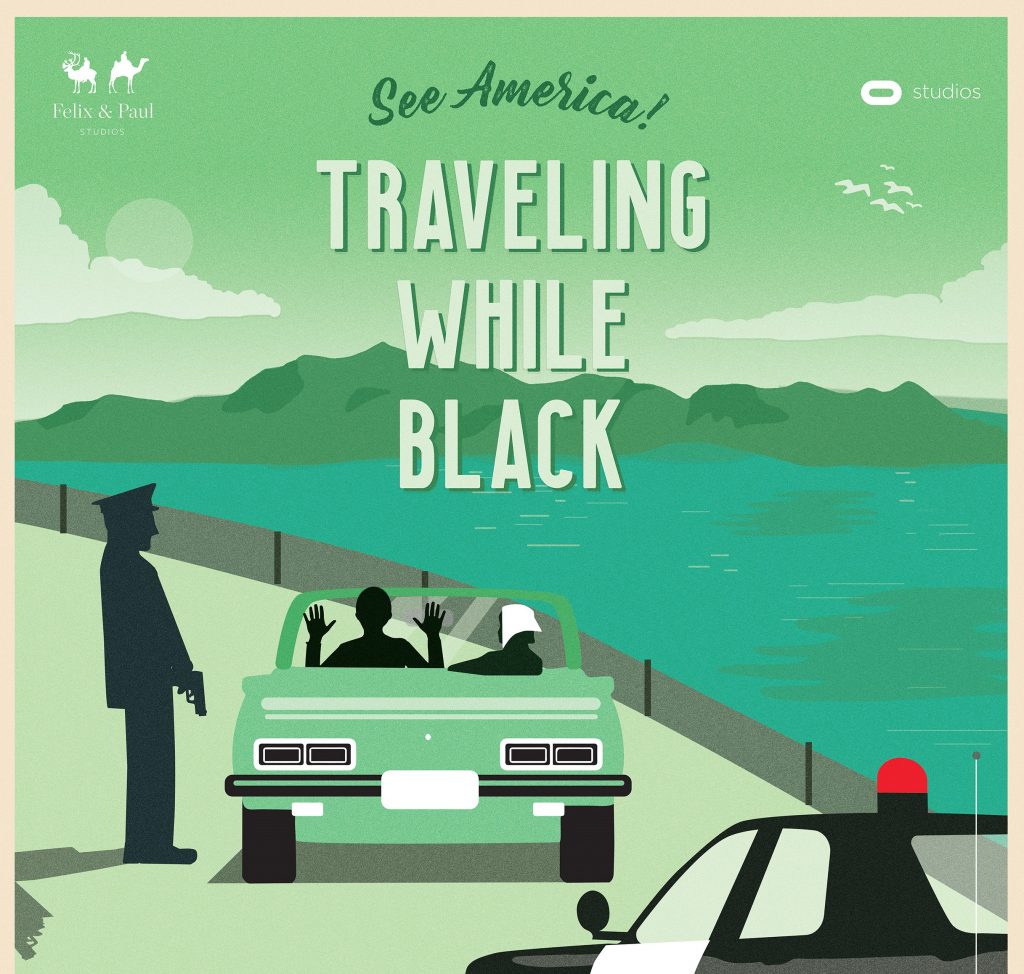

Traveling While Black

As a black person you feel a sense of relief when you enter a safe space and you don’t have to be on guard. We’re often always on guard. When I walk down the street, especially if I see a police officer, I tense up. If I’m driving somewhere and a cop car starts to follow me, I get nervous. There’s a violent history that comes with traveling while black in America and as a black person you carry that history with you.

Traveling While Black is a way to revisit that history but it’s also a way to talk about the present and hopefully start conversations about solutions for the future.

We started this project eight years ago where it began as a play in Washington, D.C., produced by Bonnie Nelson Schwartz, starring the late, great Julian Bond. We then spent several years collecting and filming stories of African-American travel before deciding virtual reality was the best platform for this film.

I chose to do this through VR because I felt this was a fresh way to have a profound conversation about race in America through a genuinely immersive lens. When you experience this documentary in VR it’s all around you and you can’t escape it. In the same way we can’t escape our blackness, or the reality of being black in America, I didn’t want people to be able to escape the experience that they’re having when they watch Traveling While Black. I wanted them to be fully immersed, and that’s something you can only do with VR.

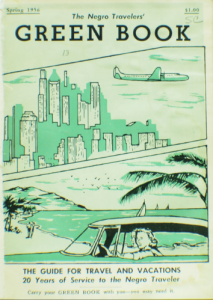

Victor Green, the author of the Green Book, writes “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States”. While the Green Book is no longer published, the need for resources and safe spaces still remains to this day. There is still an ongoing crisis in America, traveling while black is still a matter of life and death.

—Roger Ross Williams

The Negro Motorist Green Book, first published in 1936, was a critical guide for African-Americans traveling during the ’40s, ’50s and early ’60s. It was created by a Harlem postal worker, Victor Green, and his colleagues, who gathered a listing of restaurants, bars, hotels and private homes that welcomed black travelers across the country. In a time where Americans started hitting the road, African-Americans faced restrictions as they traveled. Although you could purchase a car, you couldn’t get gas, stay in hotels or eat in restaurants. Travel was difficult and dangerous. Ben’s Chili Bowl, at 1213 U Street, Washington, D.C., was originally a silent movie theater called the Minnehaha. It was later featured in the Green Book as a pool hall. Since 1958, Ben’s Chili Bowl has continued the legacy of the Green Book, providing a refuge for the whole community.

The Negro Motorist Green Book, first published in 1936, was a critical guide for African-Americans traveling during the ’40s, ’50s and early ’60s. It was created by a Harlem postal worker, Victor Green, and his colleagues, who gathered a listing of restaurants, bars, hotels and private homes that welcomed black travelers across the country. In a time where Americans started hitting the road, African-Americans faced restrictions as they traveled. Although you could purchase a car, you couldn’t get gas, stay in hotels or eat in restaurants. Travel was difficult and dangerous. Ben’s Chili Bowl, at 1213 U Street, Washington, D.C., was originally a silent movie theater called the Minnehaha. It was later featured in the Green Book as a pool hall. Since 1958, Ben’s Chili Bowl has continued the legacy of the Green Book, providing a refuge for the whole community.

— From Traveling While Black

Roger Ross Williams is an award-winning director, producer and writer and the first African American director to win an Academy Award ®, with his short film “Music By Prudence.” Williams was recently named by Variety to the New York Power List as a “digitally savvy, entrepreneurial trailblazer” in the entertainment industry. He has directed a variety of acclaimed films, including Life Animated, which was nominated for an Academy Award ® in 2016 and won three Emmys, among them the award for Best Documentary, in 2018. He also directed the 2013 documentary God Loves Uganda, which was shortlisted for an Academy Award ®.

His current projects include a documentary feature about Harlem’s legendary Apollo theater, a series for Netflix and a narrative feature film for Amazon Studios. His most recent documentary, American Jail, which examined the U.S. prison system, premiered on CNN in July 2019.

Since 2016, Williams has been on the Board of Governors for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He serves as chair of both its Documentary Branch and its Diversity Committee and sits on its Education and Outreach committee as well as its A20/20 diversity initiative. He is on the Alumni Advisory Board of the Sundance Institute, the Advisory Board of Full Frame Festival and the Board of Directors of the Tribeca Film Institute.

In addition, Williams serves on the board of Docubox Kenya, a documentary fund and mentorship program based in Nairobi that supports African filmmakers, and on the board of None on Record, a Kenya-based organization that provides media training for the African LGBT community. He is also on the board of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, South Africa, the first major African museum dedicated to contemporary art.

QUESTIONS FOR THE CREATOR

Why did you create this work?

Roger Ross Williams: I created this work to allow audiences to experience how travel discrimination impacts people’s daily lives in both small and dramatic ways and how everyday people can work together to rise above the harsh inequality in a productive, communal way. I wanted to explore how barriers to physical mobility affect other types of mobility (i.e., economic, social, spiritual) and also how communities can come together to confront these obstacles. And I wanted to collect, share, and preserve important familial, cultural, and historic memories from the Jim Crow Era before they are lost forever.

Why now?

I think we all know America hasn’t really dealt with the issues around racism, and slavery, and the legacy of slavery. The goal of “Traveling While Black” was to create a conversation about that. As black people we are always on edge, and simply existing is a risk despite the advancements in civil rights. I’m still fearful when I’m driving and see a police car behind me. Black American parents still teach their children survival skills for everyday life in the 21st century. So now is a crucially important time.

What surprised you as you were making it?

What surprised me is that when I dove into VR, people kept telling me it was like theater and I needed to think in a different way, and I experimented with lots of different ways to tell the story (animation, live action, etc.). But what I realized is that VR, like any other storytelling medium, is really about the story. And I went full circle back to my documentary storytelling instincts and I think by using those skills and those instincts I was able to create something that was totally unique and different. I learned that the power of VR, and the power of any medium, is totally contained within the power of the story.

What was the most challenging aspect for you?

The biggest challenge was doing justice to the material. I wanted this to be an impactful piece, so I was thinking about that all the time. That’s why we decided on a VR format. You can’t escape it because you are immersed in the story in such a powerful way, and you can’t be distracted by a cellphone or other device like you would be in a classic 2D experience. For example, we could surround the viewer with all-too familiar footage of the shooting of unarmed black men. We’ve all become numb to that footage in classic formats. In this format, especially if you’re not black, you are kind of placed in that reality. And if you’re not black, you also get to go into Ben’s Chili Bowl, a black safe space, and be part of a conversation there that you probably wouldn’t normally have access to. If you are black, the VR is like therapy. It lets you delve deep into that inner trauma that we all carry with us in America as black people. But the immersion was challenging too, because you don’t want to overwhelm the audience. So finding the right balance was its own challenge.