Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison

HUMAN SLAUGHTERHOUSE:

MASS HANGINGS AND EXTERMINATION AT SAYDNAYA PRISON, SYRIA

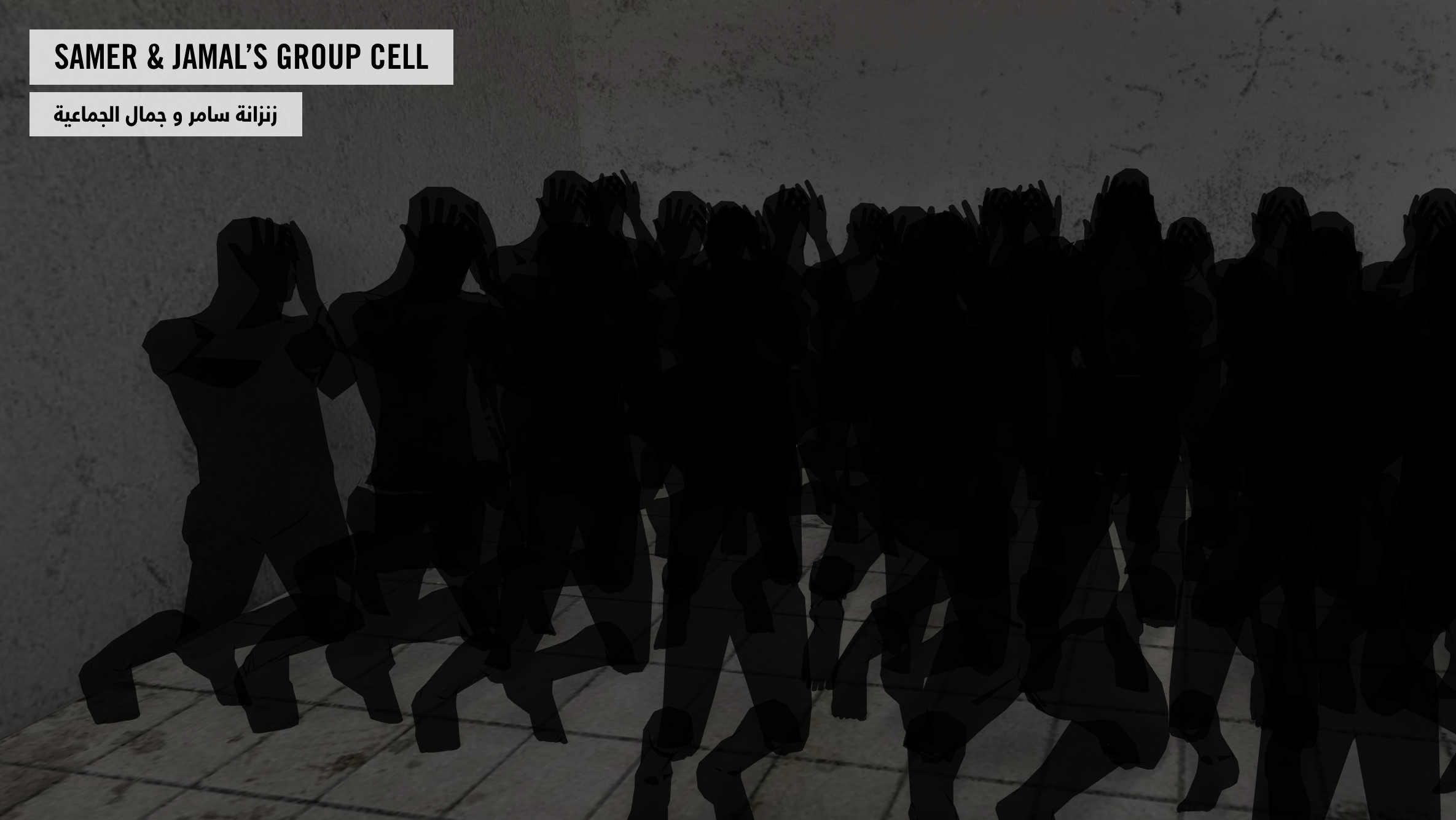

At Saydnaya Military Prison, the Syrian authorities have quietly and methodically organized the killing of thousands of people in their custody. Amnesty International’s research shows that the murder, torture, enforced disappearance and extermination carried out at Saydnaya since 2011 have been perpetrated as part of an attack against the civilian population that has been widespread, as well as systematic, and carried out in furtherance of state policy. We therefore conclude that the Syrian authorities’ violations at Saydnaya amount to crimes against humanity. Amnesty International urgently calls for an independent and impartial investigation into crimes committed at Saydnaya.” — Amnesty International

A survivor works with a Forensic Architecture specialist in Istanbul to reconstruct the prison at Saydnaya.

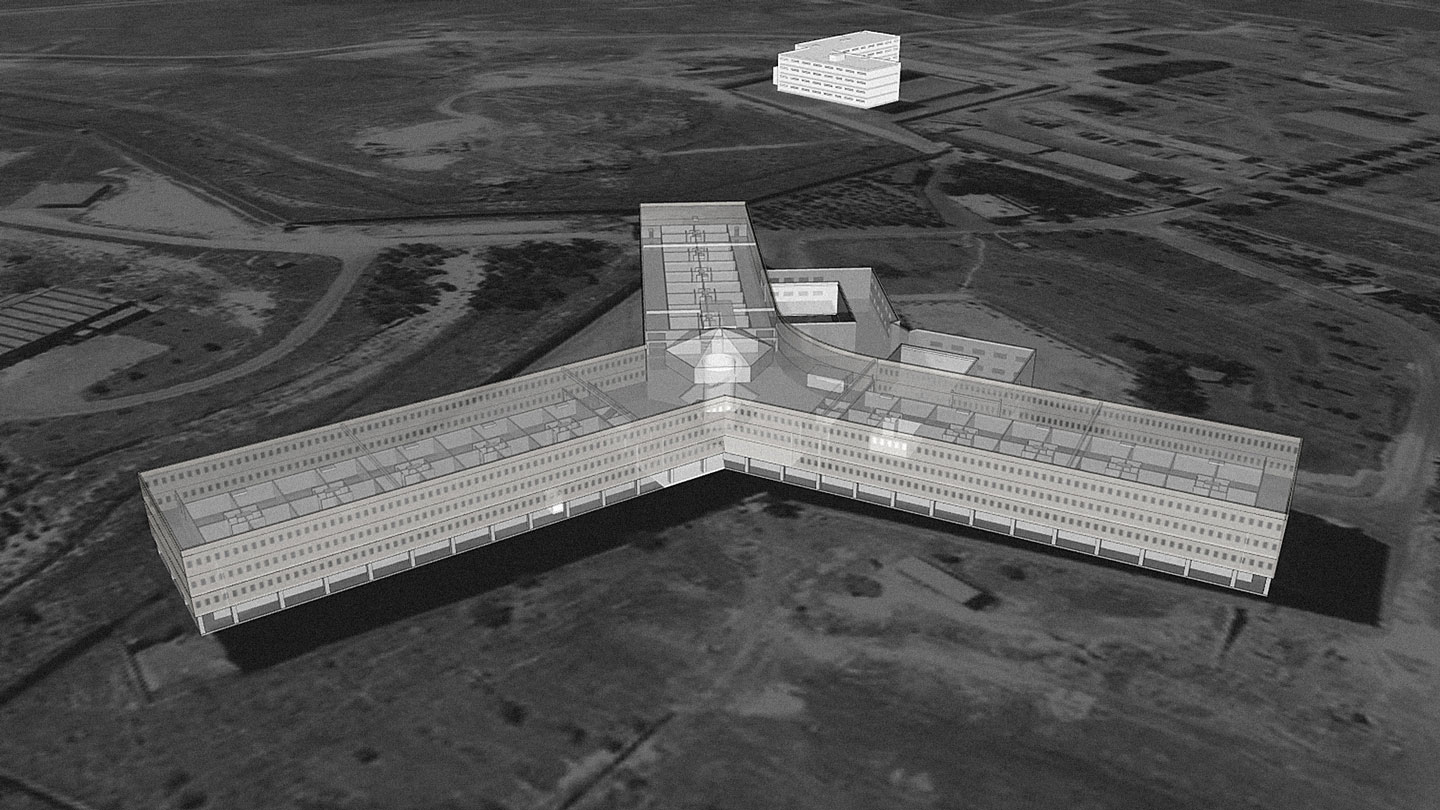

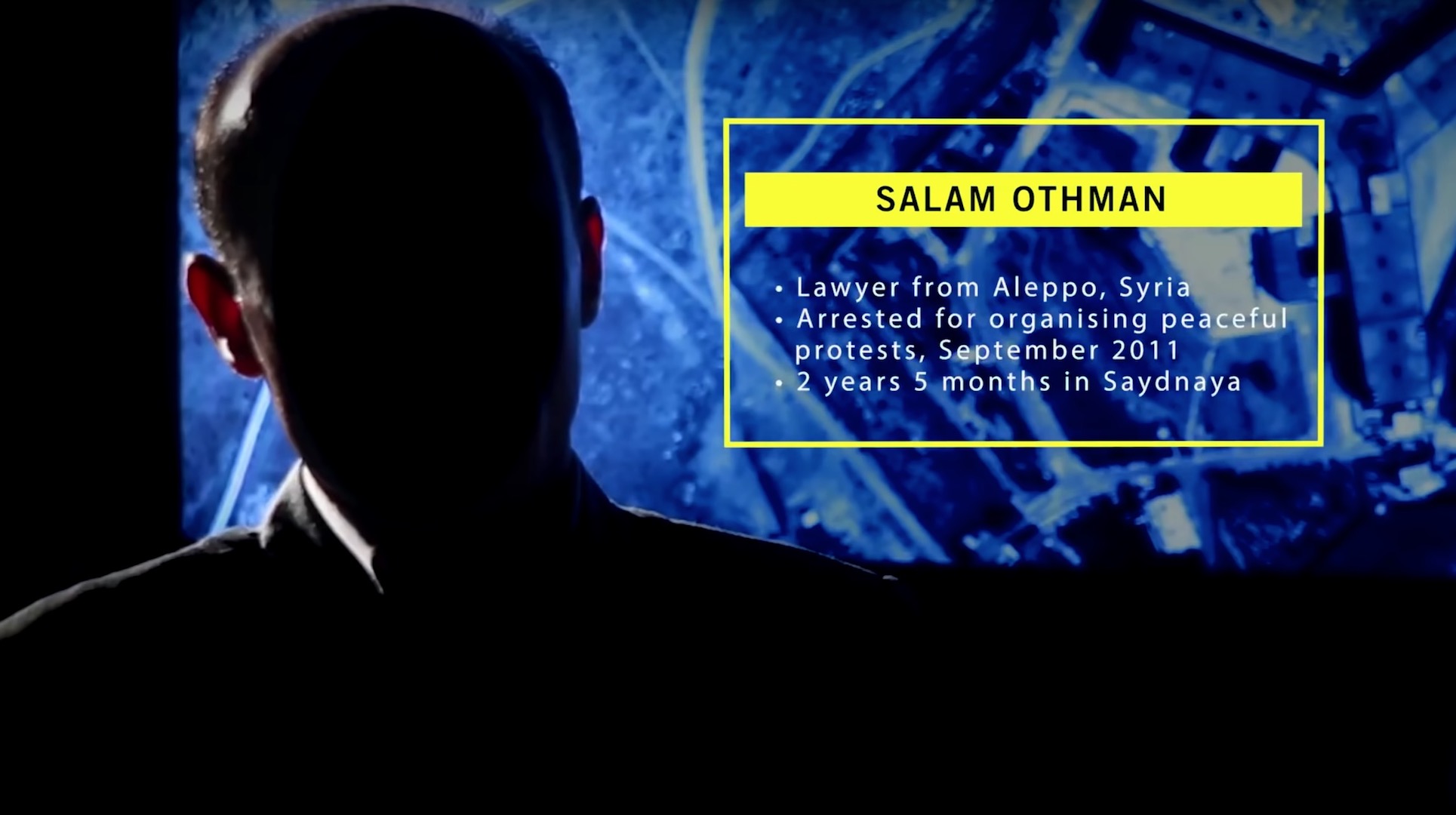

In 2016, Amnesty International teamed up with Forensic Architecture to build an interactive 3D model that would recreate the horrors of Saydnaya, the Syrian torture prison near Damascus. No journalists or monitoring groups that report publicly had been able to visit the prison or speak with prisoners for years. But that April, people from the two organizations traveled to Istanbul to meet survivors from the prison.

As there are no images of Saydnaya, the researchers were dependent on the memories of survivors to recreate what has been happening inside. Using architectural and acoustic modeling, the researchers helped witnesses reconstruct the architecture of the prison and their experiences of detention. The former detainees described the cells and other areas of the prison — stairwells, corridors, moving doors and windows, torture tools, blankets, furniture — to an architect working with 3D modeling software. Inevitably, each recollection sparked more memories as the model developed.

The Forensic Architecture team at work in Istanbul.

Eyal Weizman is the founding director of Forensic Architecture, an agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London, that undertakes advanced architectural and media research on behalf of international prosecutors, human rights organisations, and political and environmental justice groups. As a discipline, forensic architecture is an emergent academic field developed at Goldsmiths that refers to the production and presentation of architectural evidence – buildings and urban environments and their media representations. The premise of FA is that analysing violations of human rights and international humanitarian law requires modelling dynamic events as they unfold in space and time, creating navigable 3D models and interactive cartographies of sites of conflict.

Weizman is also Professor of Spatial and Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths and the author most recently of Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability (Zone Books, 2017). A native of Israel, he is on the board of directors of the Centre for Investigative Journalism in London and on the technology advisory board of the International Criminal Court in The Hague. He has worked with the United Nations and with NGOs worldwide.

“Working with Amnesty International, Forensic Architecture interviewed five former Saydnaya detainees in Istanbul. The researchers asked the prisoners to describe the building. Trauma unhinges memory, but architecture can provide an anchor. No detail was considered too trivial. Based on remembered smells of grease and blood, and sounds like an idling truck engine delivering new prisoners or the approaching thud of guards beating inmates, cell by cell, Forensic Architecture constructed a computer model of Saydnaya.

“‘When a state commits a crime,’ Mr. Weizman explained, ‘it cordons off an area, which is the privilege of the state. That site becomes a work of architecture, defined by the cordon. . . . You can try to break through the state cordon via leaks, media images, satellite photographs. And when they’re not available, memory is a way around the cordon.’”

“The material is harrowing: to see, for example, from several CCTV camera positions, the daily life of an Aleppo hospital in the seconds before it is obliterated by pro-regime forces. ‘You never get used to it,’ says Weizman.”