Westworld (Season 1)

Given all the time you spend thinking about what it means for an android to be increasingly human, what would you like to say to A.I. designers?

Jonathan Nolan: Stop.

— Esquire, April 23, 2018

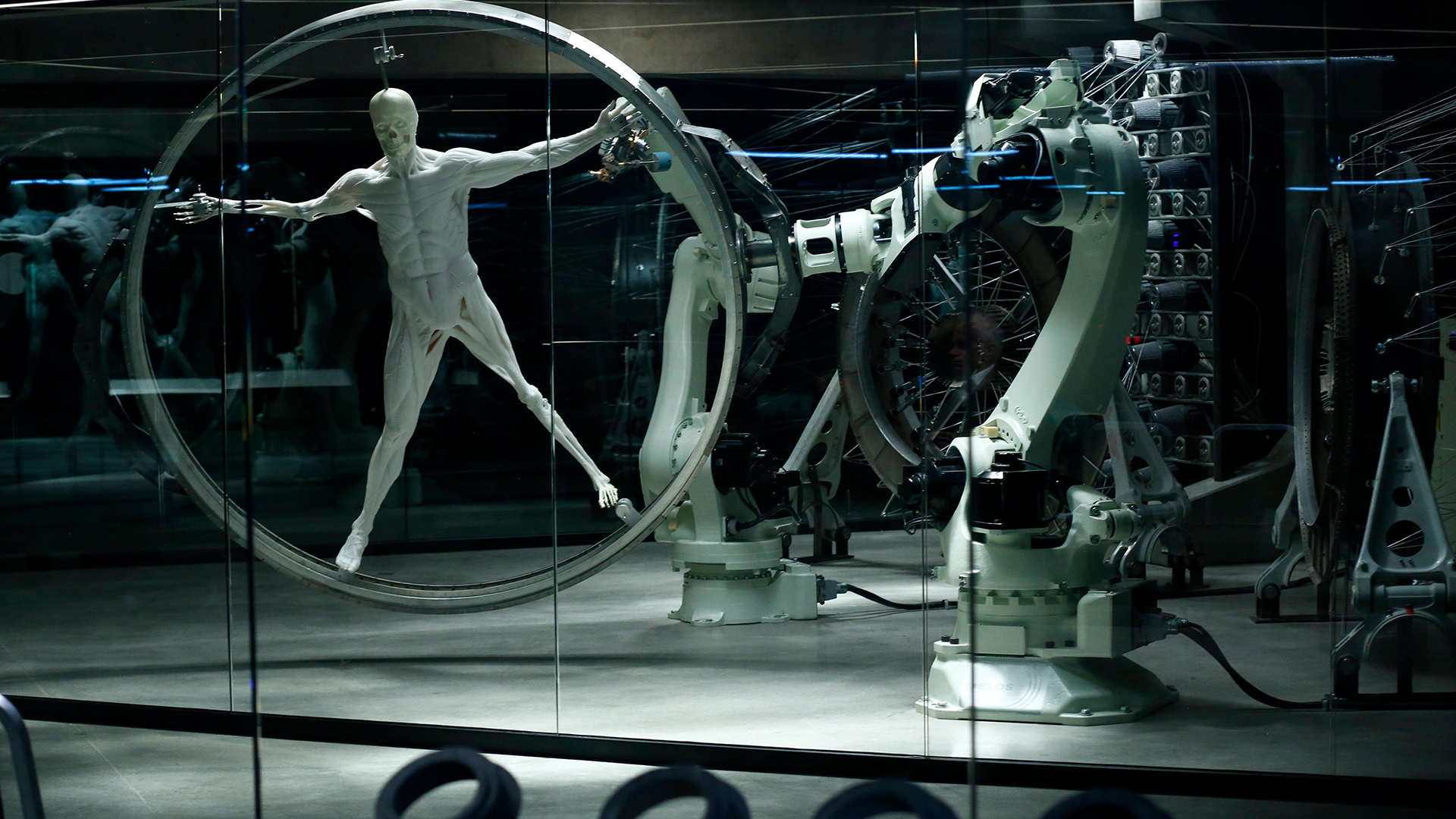

HBO’s Westworld averaged nearly 12 million viewers per episode during its first season — not bad for a hyperviolent yet oddly cerebral television show that focuses on moral questions around A.I. from the robots’ point of view. Created by the husband-and-wife team of Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy and executive-produced by J.J. Abrams, the series offers up worlds within worlds, riddles within riddles, and characters who are caught in endless loops that they’re not supposed to remember — but clearly are beginning to.

What’s remarkable from the Lab’s perspective is not just how layered the story is but how layered the storytelling itself becomes: Even as the show delves into ethical issues between action sequences, it also explores the nature of interactive narrative and the possibilities that come into play when you take audiences behind the screen and into the workings of the Westworld theme park and of Delos, the corporation that owns it.

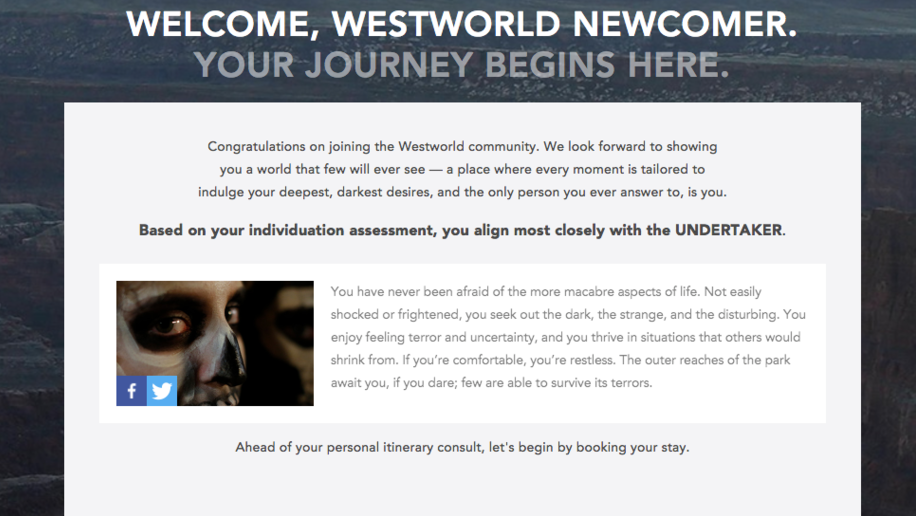

Beyond the show itself, many aspects of which were deliberately puzzling and enigmatic, HBO created a vast network of Web sites to build out the story world online. DiscoverWestworld.com, built by Reaktor and Digital Kitchen, served as the main portal to the park. The site featured an A.I.-powered chatbot named Aeden, created by Google Zoo and rehabstudio and scripted by Nolan and Joy, that would ask you some questions, assess your personality type and plan your “visit” to Westworld accordingly. Would you wear a Black Hat or a White Hat? Were you an Outlaw or a Homesteader — or maybe an Undertaker? Aeden would know.

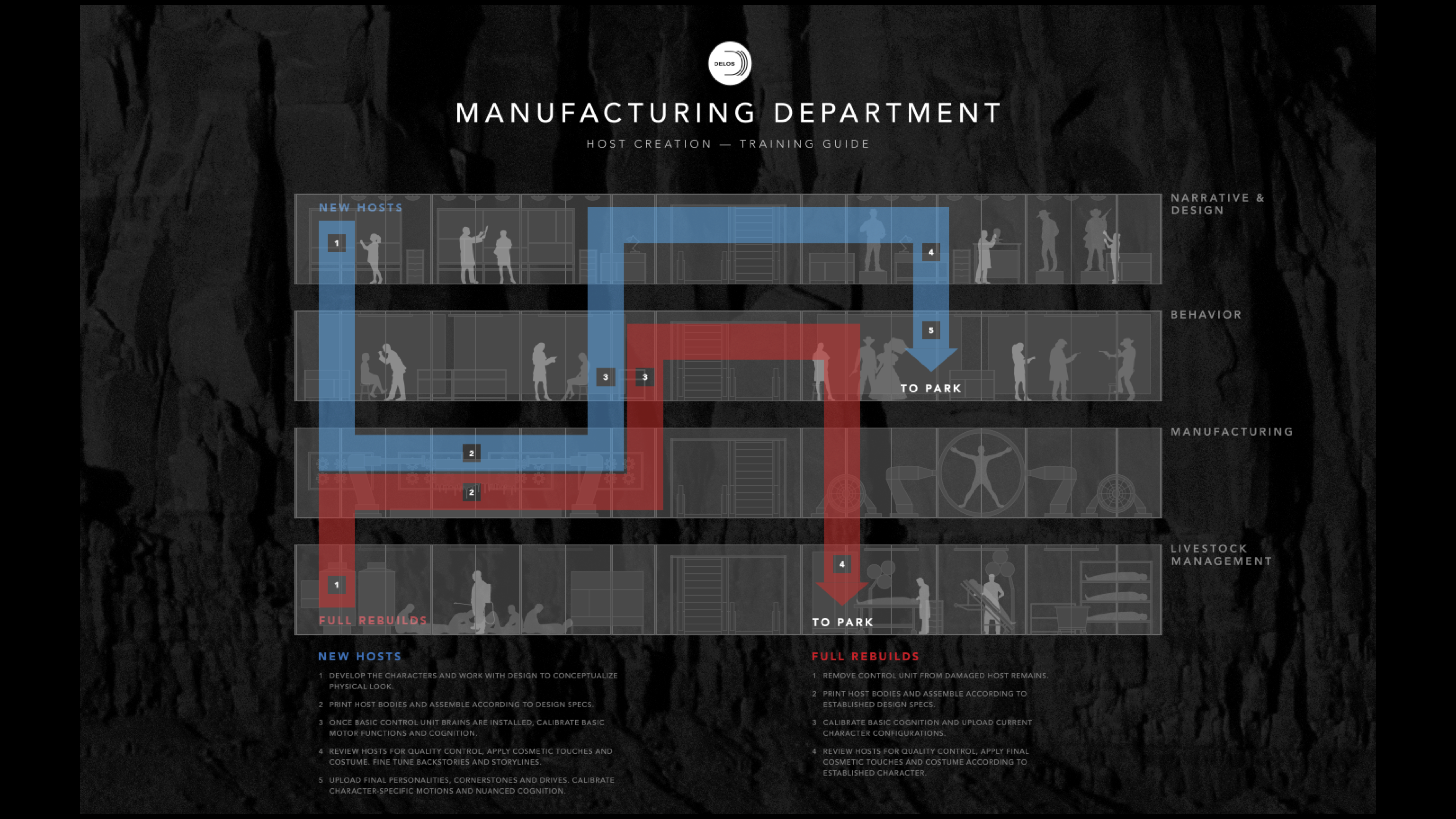

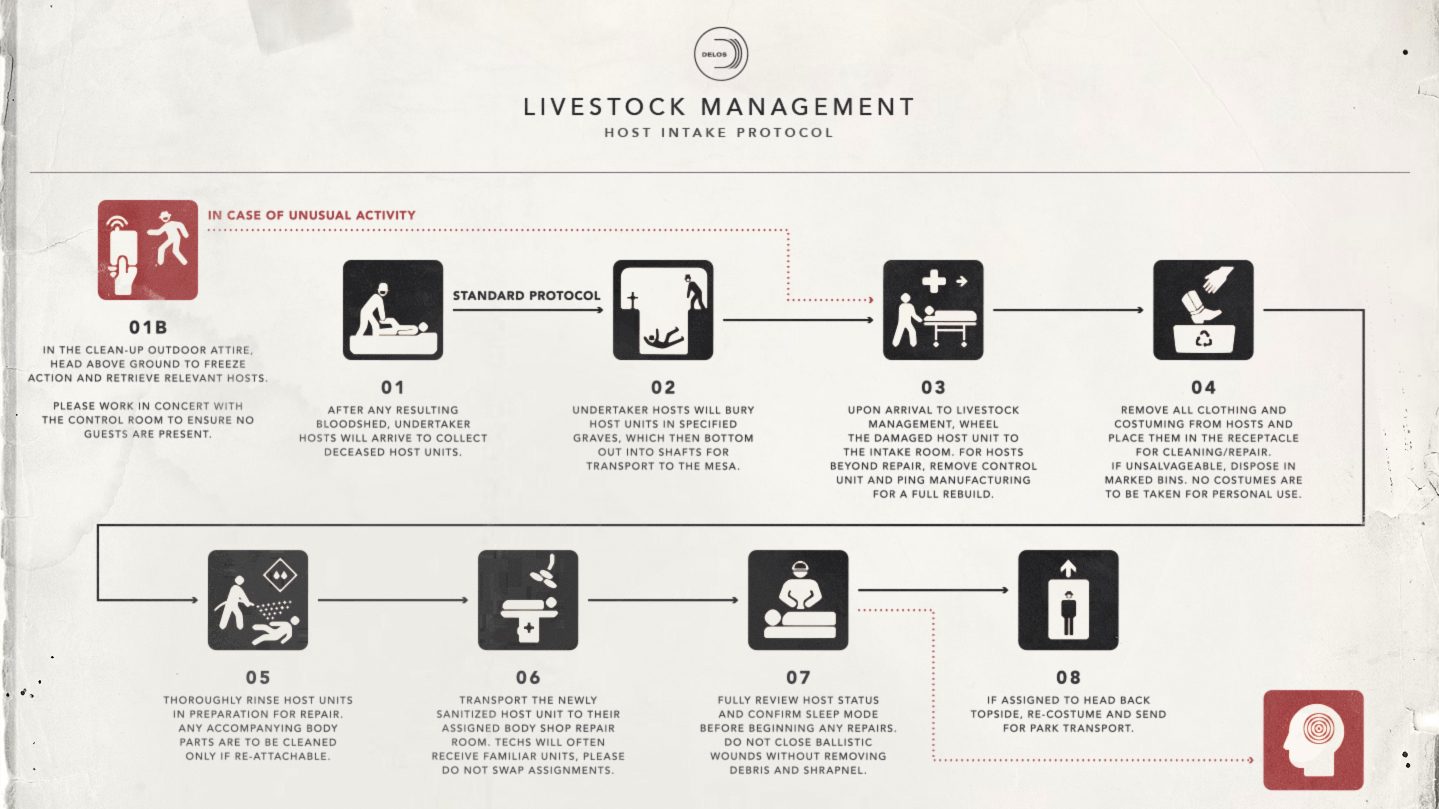

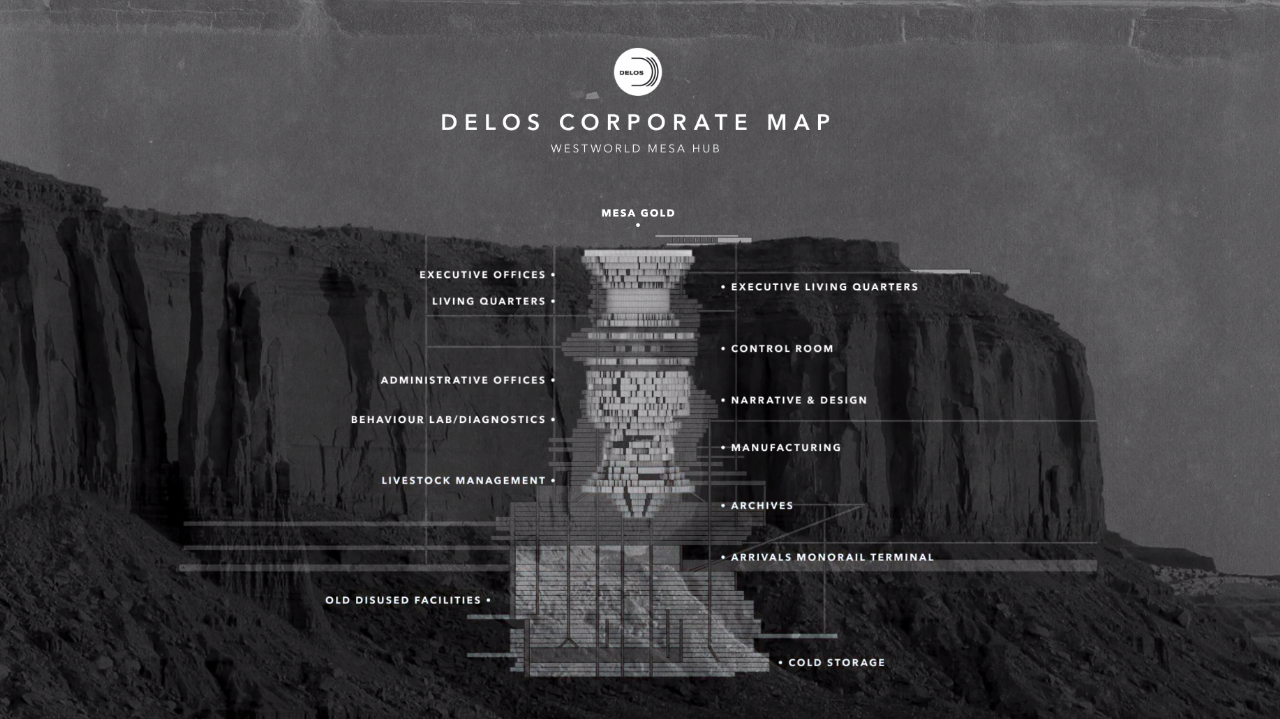

Meanwhile, in the upper right corner of your computer screen, there was a box mysteriously labelled “Access.” Typing the right phrase into it would take you to DelosIncorporated.com, where you could gain access to various “corporate resources” — for example, a Storyline Builder Template that mapped out the daily loops for Dolores Abernathy (Evan Rachel Wood), a central character among the hosts: if this happens, then that, and so forth. Lurking within the sites’ code were Easter eggs that kept changing as the season progressed, offering hints about the series’ strangely warped timeline early on, later suggesting the robot uprising that increasingly seemed fated to come.

Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy. Illustration by Ben Kirchner | source photo by Emily Berl for The New York Times

Jonathan Nolan had the idea for Memento, his brother Christopher’s first film, and published it as a short story in the March 2001 issue of Esquire. Jonathan went on to write The Prestige, The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Rises, and Interstellar with his brother and to create the television series Person of Interest with backing from J.J. Abrams. He met Joy at the premiere of Memento; the two were married in 2009.

Lisa Joy started her career in Hollywood as a consultant at McKinsey & Company and then took a job in corporate strategy at Universal. She went on to get a law degree from Harvard, but her real interest was writing. A spec script got her hired as a writer on ABC’s Pushing Daisies; later she worked on the spy drama Burn Notice. With an immigrant background — she was raised in New Jersey by an English father and a mother from Taiwan — it was she who saw the potential when Abrams suggested they reinvent Westworld, Michael Crichton’s 1973 movie, as a TV show told from the robots’ perspective. Westworld is the first project she and Nolan have worked on together.

“It's not only a question the humanoid machines at the heart of ‘Westworld’ must answer from time to time but also a question that the new HBO series is posing for the audience, as it immerses viewers in a world populated by robot avatars that just might have more personality and longer memories than it seems. Citing popular video games like ‘Red Dead Redemption’ and ‘Grand Theft Auto’ as touchstones, ‘Westworld’ showrunners Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy see ‘Westworld’ as engaging the idea that every action has a consequence, even (and perhaps especially) in the face of heightened realities.”

“Interactive fiction — whether the kind you find in video games or the sort that Nolan and Joy had to invent and run beneath the narrative hood of ‘Westworld’’s overarching story — presents peculiar challenges. . . . The problem is that so many video games choose to tell stories about small groups of people blasting their way through large groups of people — which is the very activity many of the fictional visitors to Westworld decide to pursue for themselves. These sorts of stories, no matter how artfully they’re presented, are always pretty conceptually dumb, and I say that as someone who enjoys writing them. The fascinating achievement of ‘Westworld’ is that it dares to take seriously the creative and experiential dilemmas that interactive video-game stories pose.”

“It’s an approach that makes ‘Westworld’ seem more like a puzzle than a story, and encourages viewers to maintain a wary distance from what’s being shown onscreen, turning watching into an exercise in spot-the-tell. ‘Westworld’s craft — its design, direction, and performances — is admirable, and its ideas about artificial intelligence, fate, and narrative are intriguing. But too often the show feels like a clue-hunting exercise, the narrative equivalent of a point-and-click adventure game — a show that doesn’t want to be watched so much as solved.”